Summit on the temporary revocation of the planetary status of the Earth

Attending: Approximately 85,000 geologists and 53,000 astronomers

Motions 1–3:

Dr. B submits on the requirement that a body must have cleared its orbit; that the Earth has failed due to the 13,500 tons of Earth-origin material—in addition to an unknown quantity of space debris past Earth’s orbit but in the legal jurisdiction of Earth—now captured within the orbit of the Sun and other bodies.

The motion passes.

Dr. H submits on the requirement that a body must have achieved differentiation and reached hydrostatic equilibrium; that the Earth has failed due to the physical and psychological fracturing of the Earth’s upper crust through fracking, ocean-floor drilling, and the deployment of 2,000-pound bombs into human bodies, tents, and sand in occupied Palestine by Western political entities.

The motion passes.

Dr. W submits on the requirement that a body must orbit its star; that the Earth has failed due to the central politics of annihilation prevailing in the world.

The motion passes.

Defining anti/science

Scientists are revolting—or, they’re telling us they are. The US administration’s mass reduction of federal funding and workforce across the sciences—for instance, planned cuts of 30 percent at the Department of Health and Human Services,1 about 50 percent of NASA’s budget,2 and 75 percent of scientific researchers at the Environmental Protection Agency3—threatens to impact not only research carried out by federal workers but also graduate students holding grants from these funding bodies; researchers at universities, research institutes, and private companies; and education programs supporting K-12 and university STEM education. Coinciding with national Stand Up for Science marches,4 science advocacy groups5 and academic societies6 have raced to issue tool kits, alerts, and centers calling for “action.” They have also filed legal suits for scientists to challenge these policies.7 This movement has resurfaced a term that emerged from the current president’s previous tenure: “antiscience,” an anti-intellectualism correlating with right-wing ideology concerning primarily vaccines and climate.8

Notably, these “defiant” actions are led by organizations that have been absent from the actions of the Student Intifada, silent about Columbia graduate teaching assistants being reprimanded for teaching their students about astronomy in Palestine,9 and quietly feigning ignorance about Palestine Action targeting genocide-profiteering companies that employ STEM workers (all while unmasked and unbothered, because the CDC said so).

As a planetary geologist, I’ve watched as my peers over fourteen years of space education programs and research trainings have overwhelmingly disappeared into the war machine, now engineering missiles, nuclear submarines, surveillance satellites, and fighter jets for the companies facilitating genocide in Palestine and global imperial plunder, or otherwise working shoulder to shoulder with those companies on space missions. Collectively, we in the space industry and broader Western academia consider these activities “science,” on an equal plane with any and all other scientific inquiry and development, and therefore worthy of “defense”—but not the Palestinian people, or those who advocate for the Palestinian cause.

It is pressing, therefore, to define “science” and likewise “antiscience.” Is the “science” for which we advocate the abstract scientific method, the concepts of vaccines and obstetrics and astronomy, the workers of STEM fields, the policies that emerge from research, the applications of our research, its political economy—or something else entirely?

Is science equally the surveillance satellite and the COVID vaccine? (And what of the expired vaccines the occupation delivered to Palestinians in 2021?10) Is science the manufacturer of the missile as well as the community garden? Is it the 200 Glock firearms for NASA security officers to police the border,11 and the sandstones on Mars?

The practice of Western science in many ways originates with the Enlightenment philosophers. After more than a century of violent European settler colonialism and the enslavement of Africans, Taíno, and other Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island, the Caribbean, and South America—which cemented a shift from mercantilism to capitalism hand in hand with these extractivist policies—Europe’s seventeenth-century intellectual revolution fundamentally re-centered truth from inside the church to within the scientific method. In this new intellectual order, nature became objectively observable through empirical study and experiment. This methodology spawned new areas of study, coalescing previous European intellectual work and co-opting the scientific approaches of the Global South. For example, Nicolaus Steno is credited with founding modern geology as well as being an important philosopher of science, recording principles of the scientific method and distinguishing these methods from religion.12

In this regime, the scientist in early capitalist Europe became external to the system of wage labor—replacing the noble, priest, even God as the seeker of (finite, objective) truth and becoming an intermediary between that empirically derived truth and the commoners. The scientist was not part of Earth; instead, he studied it as a distant, divine entity, ordained with a moralistic responsibility. The human body was not part of the Earth, either. The role of the human was to study the world, empirically—knowledge (scientia) as something to produce concerning the land but never on it, within it, or tied to it—and the human, implicitly, was narrowly defined.

And so, Empire’s new empiricism was not neutral. The scientific method became the third hand, so to speak, with capital and Empire—if you can define objective truth, and contain it within bounds that you control, you can capture any knowledge as “true” or “untrue” within any broader project. Thus formed the world, and Western science: The scientist emerged as the student, God, lord, and purveyor of truth on behalf of Empire. As the purveyor of truth, the scientist was embedded in the process of categorizing and delineating reality, pinning arbitrary qualities, practices, and lands into new orders of race, gender, disability, and sexuality, particularly tied to labor. Amílcar Quijano describes the construction of race in terms of modernity on the same temporal scale as this new order of “objective” scientific knowledge:

All non-Europeans could be placed vis-à-vis Europeans in a continuous historical chain from “primitive” to “civilized,” from “irrational” to “rational,” from “traditional” to “modern,” from “magic-mythic” to “scientific”; in sum, from non-Europeans to something that could be, in time, at best Europeanized or “modernized.”13

For example, the scientist’s map became an action in the name of political motivations and ideology—not a static paper-based object. The empirically derived map erased social, cultural, and political realities of land, rendering Turtle Island—and not much later, Palestine—empty of humans and therefore exploitable (“terra nullius”); its Indigenous people “primitive” on this temporal scale, and thus eliminable and enslave-able; and Empire as the injection of a rational settler “civilization” into the less-than-human.14

Science and antiscience—what is this interplay if not the dichotomy of “rationality” and “irrationality” in Empire’s racial capitalist world order?

The martyred Palestinian revolutionary, intellectual, and educator Basel al-Araj wrote in his essay “Exiting Law and Entering Revolution” that “every social and economic authority necessarily intersects with and is an extension of political authority.”15 As a system of authority of “what is knowable with respect to the knower so as to control the relations among people and nature and among them with respect to it,” according to Maria Lugones in her expansion of Quijano’s framework of coloniality,16 science is a site at which political authority manifests, and therefore where it can be disrupted. It is perhaps one of the first sites: al-Araj wrote separately that “the first thing that colonialism does is establish what is possible and impossible for oppressed peoples.”17

Understanding science as a form of political authority is therefore crucial to understanding the role of the scientist within Empire—and the pathways for defying this political authority. I focus on space science as a site of potential because of its critical embedment in the very material conditions of genocide—from manufacturing weapons for the zionist entity to ideological consent-making at the cultural scale, to the buildings designed for this manufacture. Space science, in all its deceitful constructed blankness, shows us exactly how science operates politically as a system of knowledge embedded in, and reproducing, power.

With you, however, I am going to write a different story.

Political authority of space

Summit on the temporary revocation of the planetary status of the Earth

Motion 4:

F.C. submits into evidence a jar of sand. The accompanying report is authored by the sand, with signatories of schist,18 terra rosa,19 and kurkar20 (see Supplement G-18).

The sand submits that it had no say in the formulation of planetary definition criteria, and they should be considered voided until new criteria are generated; in the meantime, the Earth must be considered to have failed qualification as a planet.

The motion passes.

Origins of the space industry

The US space industry (and the broader Western space infrastructure) arose from military rocket development during the 1940s after the Second World War. In 1945, the United States recruited SS officer Wernher von Braun through Operation Paperclip, a program that enabled the US government to employ Nazi scientists who were thereby protected from persecution under international law.21 Von Braun was an influential figure in developing rocket technology for Nazi Germany, using forced laborers at the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp to build the V-2 rocket.22 The US government intended for von Braun to adapt this technology for both space and military uses, including the Saturn V rocket for what would become NASA and the Redstone and Jupiter missile programs for the US Army. He gained significant influence, holding critical roles in both the defense and space programs during the Space Race, culminating in his appointment as director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960 and being invited to lead NASA strategy in 1970.23

Von Braun’s lesser-known colleague Arthur Rudolph first directed V-2 manufacturing in underground tunnels at the concentration camp, and after Operation Paperclip headed the Saturn V program as well as the Redstone and Pershing missile programs for the US Army (and consulted with the United Kingdom on their V-2 rockets). NASA awarded Rudolph its Distinguished Service Medal in 1969, the year the Saturn V first took astronauts to the moon. In 1984, almost forty years after he was recruited, the US Justice Department made a deal with Rudolph in which he would renounce his US citizenship and return to West Germany to avoid charges for the war crimes of using slave labor at the Dora-Nordhausen camp from 1943 to 1945. The investigator on Rudolph’s case—which drew no comment from NASA—explained at the time that there had been no investigation into these war crimes because the state had looked “at these people as scientists.”24

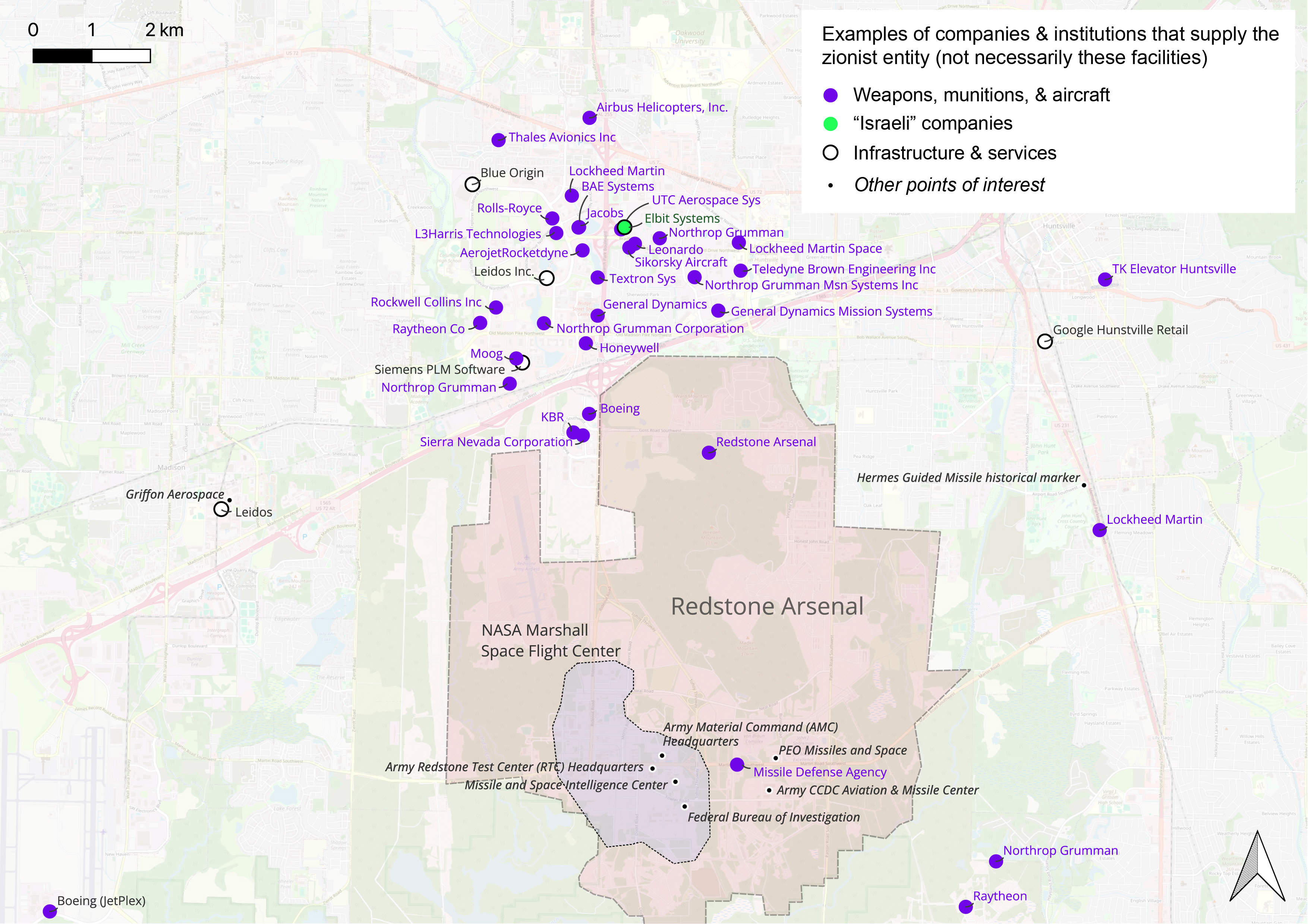

Von Braun’s legacy is largely positive at NASA, which educates the public about him being the “greatest rocket scientist in history” and his childhood interest in astronomy;25 credits von Braun for racially integrating the federal government in the 1960s;26 and hosted the 17th “Von Braun Space Exploration Symposium” at Marshall Space Flight Center in 2024.27 The center, physically surrounded by weapons manufacturers, sits on the Redstone Arsenal campus along with the Missile Defense Agency, whose administrative building is called the Von Braun Complex. Rudolph’s name is mostly absent from NASA’s webpages.

The moral and cultural sanitization of Nazis is entirely coherent with the fascist settler project of the United States. However, science played a crucial role as a fulcrum. The blank, malleable notion of science was instrumentalized to justify the recruitment of these Nazis and shield them from legal ramifications while also serving as crucial glue for the “civilian” and “military” applications of dual-use technologies. Were the rockets primarily for civilian purposes, or military ones? There was no meaningful separation, because it was all equal under the umbrella of fundamental scientific research.

As the relationships between NASA and the US defense apparatus persisted in the ensuing decades through shared personnel, dual-use technological development, and physical architecture, so did this deployment of “science.” Loci of “space science” draw a map of imperialist expansionism: the early colonial observatories in South Africa;28 telescopes in occupied Kashmir, Okinawa, Mauna Loa (and attempted on Mauna a Wākea); space launch facilities in Woomera (next to a military base and a mass detention center for migrants), so-called Australia, and French Guiana;29 and fieldwork and analogue sites in the Naqab, Devon Island, and Mauna Loa. Facing opposition from Indigenous resistance, these sites have overwhelmingly been legally and politically justified by occupying imperialist powers in two ways: through colonial terra nullius policies and the argument that these facilities serve the “greater good” of society.30

These shifting goalposts of moral justification, manifesting in the legal and political as well as the technological arenas, can be seen as a form of ideological authority. Basel al-Araj described the law as “a tool for normalization and hegemony at the hands of power.”31 Law, like and alongside science, defines what is knowable, how it can be known, and places bounds around derived knowledge as a system of political authority. If it’s legal, would we still oppose it? If it’s conscripted into the greater good of “science,” would we still oppose it?

The beginning of every revolution is an exit, an exit from the social order that power has enshrined in the name of law, stability, public interest, and the greater good.32

Space in the present day

The Palestine Space Institute (PSI) therefore names the present-day material context of space and the military-industrial complex as three primary entanglements: economic, technological, and ideological.33

In 2024, PSI released a database and report on over 50 companies we identified to both be active in the space sector and supply the zionist entity with arms, missiles, ammunition, bombs, aircraft, chemical weapons, cyberwarfare technology, fossil-fuel infrastructure, and more. The report exposed $39 billion in NASA expenditures to half of these companies, amounting to 50.2 percent of NASA spending. The contracts with NASA show a mix of dual-use technology supply (e.g., missile/rocket development; computing hardware for Mars rovers), and basic research often in partnership with the Department of Defense on building more “sustainable” (faster) aircraft, testing the limits of the “civilian” half of the term dual-use. In one case, the Boeing contract on file shares an address with the facility manufacturing JDAM missile-guidance systems for the 2,000-pound bombs that the zionist entity has used numerous times to kill Palestinians in Gaza since October 2023.

One might seek to distinguish between the engineering aspect of space exploration and the resulting science. However, the study of planetary science is not abstracted from these material relationships; it is a vital part of the ideological entanglement between space and Empire.

Every study of planetary geology is inward-turning. It is a reflexive practice. As a researcher in planetary geology, the fusion of astronomy and terrestrial geology, my methods draw entirely from the study of our planet Earth. As we study sands on Mars, we use methods and frameworks tested by naturalists in the Sahara and the Naqab; as I measure the gentle tilt of rock layers in a canyon on the red planet, I contextualize what I find against best practice here. Our models and ideas always return home as a reference, placing the unknown against the legible, and that degree of legibility or illegibility becomes something else entirely.

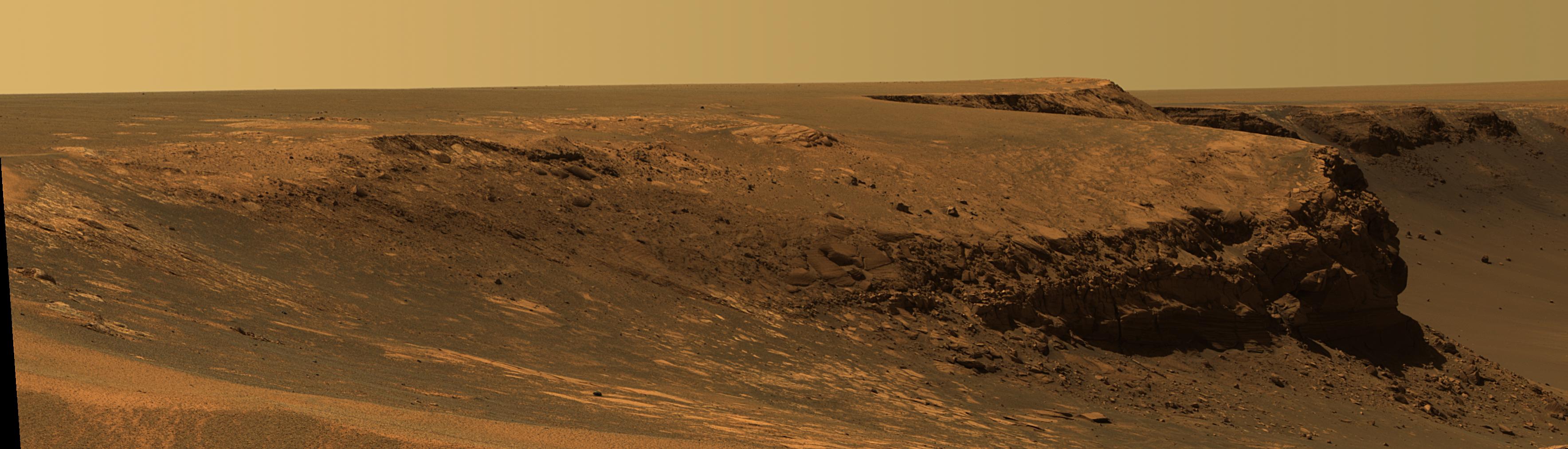

I work in planetary imaging, which is the interface between the scientist and the “public” in that convenient Enlightenment dichotomy. The choices we make in collecting, processing, and visualizing images are at the forefront of conveying the il/legibility of space. A Mars rover team understands that for planetary surfaces, in all the ways that matter, color is arbitrary and unknown.34 So they make the rocks on Mars redder than the scientists suspect they are, and the sky, so thick with dust, a deep yellow. NASA published this image in September 2006, its color gradient evoking Western films and news portrayals of Mexico and West Asia to audiences within and outside the imperial core. This visual language coincided with US-led invasions of West Asia and escalating anti-migrant policies at the US–Mexico border. For example, the same month NASA released this panorama, at least 3,709 Iraqi civilians were killed by US-led forces,35 and the zionist entity had killed at least 202 Palestinians in its Operation Summer Rains in Gaza, which continued through the autumn.36

These are not trite juxtapositions but a manifestation of science as political authority. That this Mars rover was constructed by Aerojet Rocketdyne (now under L3Harris), Ball Aerospace (now under BAE Systems), Collins Aerospace, General Dynamics, Honeybee Robotics, Moog, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, Rockwell, and Teledyne37—all companies that arm the US and the zionist entity—must be considered in context with the ways scientists and policymakers wield “science” to absent and absolve the material from the “scientific” to construct particular narratives.

Drawing the human from stone

The semiotics of these planetary images—cast in yellow, with wide, inviting horizons that emphasize emptiness and that evoke colonial imagery and imaginaries of deserts here on Earth—are again a fulcrum, drawing legibility onto Mars, an invitation to gaze, cross into, and imagine colonial domination. Acculturation to the “emptiness” and “lifelessness” of space allows us to practice drawing borders, to exercise the writing of Otherness into land—a primitivity that can be brought into the modern. An image from the Mars rover thereby provides consent for frontier-making processes that aren’t conjured up from nowhere, but from preexisting material processes and ideologies of settler colonialism, such as Manifest Destiny and zionism, that should be considered in lockstep with terra nullius policies here on Earth and how we are invited to see deserts.38 The image draws the conquerable world here and there, into stone here and there.

And we are also invited to see the image as a truthful capture of the surface, rather than as a product of labor and material conditions. This image is a mosaic stitched from individual images from the rover’s Pancam instrument; Pancams’ CCD detectors on the Spirit and Opportunity rovers were manufactured by Mitel, now DALSA Semiconductor, Inc.,39 owned by Teledyne, which supplies the zionist entity with aircraft equipment and electronic warfare technology.40 The cameras’ field programmable gate array (FPGA) was manufactured by the Actel Corporation, which four years earlier had delivered FPGAs “suitable for a wide range of military, aerospace and avionics applications, including radar, command and control, ground-based communications and advanced weapon control systems” to the US Department of Defense’s Defense Logistics Agency.41 The color filters were manufactured by Omega Optical, an optics company with a large defense portfolio,42 which between 2008 and 2014 received purchase orders from the US Air Force and Navy for optical and infrared filters and related hardware.43

In viewing this image, we look away not only from the material manufacture of space hardware but also from how space facilities are established and the consent that is pulled from us for continued domination more generally. We might consider this aspect of space science as a national cultural process that leverages a settler “intellectualism” and, as Edward Said wrote, reinforces the “imperium as a protracted, almost metaphysical obligation to rule subordinate, inferior, or less advanced peoples.”44

These ideological obfuscations extend to academic criticisms of space and Empire. There is a lot of money and energy spent on the intellectual playground of consent-manufacturing that characterizes typical inquiry on this subject—across space law, science and technology studies, anthropology, history of science, philosophy of science, and so on—that ultimately refuses to contend with material realities of space, instead debating the abstract, such as the internal ethics of settlement on other planets or renaming celestial bodies. Some of these activities are worth doing, but they must be done in seriousness. And so I ask us to consider the central, material realities of space and life here on Earth, in this very moment of multiple escalating genocides, and urgently.

A recent effort in Western science to reorient this world-making of geology is the term “anthropocene,” coined to reclaim the stratigraphic record from telling a purely nonhuman story of the planet and bring it into the story of human-driven climate change. “Anthropocene” and similar interventions45 focus on capturing “when” and “how” humans interact with geology as one-off events or periods, with a clear “before” and “after,” particularly visually.46 These approaches situate the human, or even life itself, after geology. There is a “before” that is, on the whole, blank, or perhaps even “good,” and there is an “after” that is “bad.”

Therefore, the choice of where to place the start of the anthropocene (whether named so or not) must be examined. The Industrial Revolution and later nuclear weapons development in the mid-twentieth century are the typical eras discussed as turning points in human interaction with the rock record. To name these eras—rarely is 1492 put forward—is to write human geology only in particular forms of violence, violence that is rarely even considered violence by the institutions of geology and related studies, that is, political violence. What counts as destructive? And to whom?

The earth behind us is yet another Other, a marked primitivity in the regime of modernism. But the relationship between human and stone is manifold: a simultaneous relationship, an exchange that is living as much as it is stone.

Enslavers constructed immense mass graves for the enslaved people they killed in the so-called United States. This layer of human bodies is embedded against the iconic schist that comprises the stratigraphy beneath Manhattan.47 Sixty-five-million-year-old ocean deposits enriched slavery-era cotton plantations, now the “Black Belt” of reliably Democratic-voting Black households in the American South.48 In 1825, Britain passed the Bengal Alluvion and Diluvion Act, fixing a border between land and water in the highly riverine Bengal delta: water was considered “uncivil,” and so property only meant land, transforming a flood-resistant ecology into a flood-vulnerable landscape and declaring any new sediment deposited along rivers as unclaimed and uninhabited and therefore belonging to the colonial government.49 The zionist entity and its land-grab borders have precluded scientists in Gaza who attempt to characterize water resilience from studying the morphologies and sediments that cross those borders50—the calcium-rich seashells of microscopic organisms that were alive, vibrant, and resplendent, in great numbers in the Mediterranean Sea millions of years ago enriched the seaside soils of Gaza, where Palestinians have harvested fruit trees for millennia, just as calcium-rich supernovae have fortified every human being’s teeth such that we can eat fruit at all. Amerindian peoples cultivate the soils and trees of the Amazon as Guyanese kids pave the bottom-houses in fresh mud and as Nepali mothers grind coconuts with granite uplifted from the seafloor by continental collision. Forcibly displaced children in Palestine rest against dunes in Al-Mawasi. Newtonian physics tells us that the dunes, in return for this company, caress the children, too.

You realize you are not just locked down to a cattle guard to block trucks. You have prostrated yourself at the foot of our majestic Mauna, whose malu protects you. And your back is a bridge you offer to kia'i of generations past, present, and future, crossing to meet one another, to touch noses and share ea.51

Alternatively, we may be offered aesthetically appealing notions of the moon as a “smug sack of shit”52—of any and all inquiry about space and Earth as inherently meaningless, any cultural and biological relationships with space somehow counterrevolutionary. Such reactionary notions again inscribe a violent terra nullius, “nothing there already”–ness to space just as much as the billionaire fascist does, or treat knowledge as the opposite of mythology as much as the race scientist, and therefore write the same story of the world. Nonreactionary forms of inquiry already exist outside of and outdating, outliving, and out-imagining this paradigm, such as the approach taken by the Palestine Space Institute, which centers the Palestinian concept of ‘awna;53 the resistive practices of the Níhookaa' Diyin Diné Protectors Organization, which is working toward protections for the moon;54 the commitment of the Mauna Kea protectors to āina and solidarity across the Pacific;55 and the efforts of the Bawaka Collective, which includes human and more-than-human members of Bawaka Country, who write on continuous stewardship of and with Sky Country.56

Summit on the temporary revocation of the planetary status of the Earth

Motion 5:

X.T. submits into evidence an engineering report authored by Wadi Gaza (see Supplement G-245).

Wadi Gaza submits that as long as it is occupied by the zionist entity and otherwise prevented from sustaining its people, the Earth must be considered to have failed qualification as a planet.

The motion passes.

The outlaw scientist

We must also consider who is investing in scientists, in their thousands, protesting for protections of Western science. The Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), a science advocacy nonprofit and academic publisher, released a tool kit that emphasizes the need for scientists to “speak up for the US scientific enterprise.”57 In February, the AAAS and the Science and Technology Action Committee—which comprises AAAS leadership, university presidents and vice chancellors, a slew of national ex-secretaries and commissioners, a former Republican representative, the CEO of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (a funder of the Thirty Meter Telescope58), the CEO of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (a think tank partly funded by a dozen weapons manufacturers and petroleum companies59)—launched its “Vision for American Science & Technology,” which boasts an “All-of-America approach” that “ensures our global competitiveness and national security” and avoids “counterproductive outcomes, such as unstable federal funding, that delay scientific progress.”60

Can the war machine go back to being predictable, invisibilized,61 and efficient?

On the other side of the moralistic good of science—on the other side of campus—is popular action that can be considered antiscience, depending on who is narrating the story: the interruption of science education, the demand for divestment from science and engineering companies facilitating the genocide in Palestine, the dismantlement of those companies, and broader calls that justice be centered over the “blank” slate of technological research and development. If the Cass Report62 passes as science to some scientists or indeed “the public,” is it not antiscience to block and overturn government policies based on its eliminatory anti-trans recommendations? If an oil pipeline or telescope desecrating sacred land employs our grad school colleagues, is it antiscience to literally put one’s body in front of the colonialist machine?63 Is it antiscience to drive Elbit out of the country?64 Throw a rock at a bulldozer?

Basel al-Araj offers us the possibility to exit the law, so perhaps we can exit science.65 At L@s Zapatistas y las ConCiencias por la Humanidad, a revolutionary scientific conference hosted in 2016 and 2017 for Indigenous students representing collectives of the EZLN, Subcommandante Galeano spoke to an audience of visiting scientists and delegates, offering a script for the scientist to revolt:

We want to learn and do science and technology to win the only competition that is worthwhile: that of life against death.66

The question in this moment is how to begin. Crucially, al-Araj conveys the potential of the outlaw: a figure who, like the revolutionary, navigates underworlds, rejects the law as a system of injustice, and inspires the masses—factors that, despite different goals initially, have famously radicalized outlaws into revolutionaries, what he calls a “smooth transition.” To wrench the reins of this authority, to redefine possibility, to rewrite the world, I offer the outlaw as the first stage for the revolutionary scientist. Perhaps the scientist, too, can exit the political authority of science. What would it mean for the scientist to cast off “authority’s tricks and lies, nor [be]… subject to its discourses, tools of mediation, and manufacturing of public opinion?”67

Summit on the temporary revocation of the planetary status of the Earth

Motion 6:

Dr. T.M. submits that this is not how the planet is meant to be lived.68

The motion passes.

In the alleyway outside the academy

In his essay “‘A Productive Language’: On Western Intellectual Paradigms and Refaat al-Areer,” Ameed Faleh discusses the martyr Dr. Refaat al-Areer’s legacy in context with Palestinian revolutionary and writer Ghassan Kanafani, Iraqi Marxist Hadi al-Alawi, and the mathematician, medical doctor, and resistance leader Fathi al-Shiqaqi, emphasizing the importance of producing “a new language that appeals to the common people and unites them under revolutionary principles”—such as through storytelling.69

Meanwhile, al-Araj encourages us to consider the role of the romantic in our biographies of revolutionaries in “Why Do We Go to War?”70 while Salaita argues:

It’s too late for nostalgia or romanticism. The university can no longer pretend to be a benighted site of inquiry and erudition, some peaceful, hermetic landscape outside of “the real world.”71

The absence of this romance of inquiry opens up new possibilities. The outlaw scientist might start here: productive, collective, and romantic storytelling of unmaking, refusing, and gazing back to supplant the myths of modernism. How can the engineer become the de-engineer of the war machine, uncivil to the police state? How can the mapmaker obscure Indigenous land from surveillance?72 How can the syllabus, scientific method, laboratory manual be unwritten, torn up, and wheatpasted in order tell the truth and lead us to community-building, political education, and praxis in the underworld or the alleyway beyond the academy? What productive language can we formulate against science constructed for annihilation—oral, written, stashed in a hiding spot?

If we’re going to say we lived

Science is the story of the world. Or, science is the story of who has written the world into, and out of, existence. Or, science is the craft of making and unmaking life.

To our productive language, I close with the submission of a poem. Revolutionary intellectual Nâzim Hikmet reaches through time to ask us, perhaps the planetary geologists most of all, to take living seriously. In living, the scientist in their laboratory might “die for people— / even for people whose faces you’ve never seen.”73

This earth will grow cold one day,

not like a block of ice

or a dead cloud even

but like an empty walnut it will roll along

in pitch-black space. . .

You must grieve for this right now

—you have to feel this sorrow now—

for the world must be loved this much

if you’re going to say “I lived”

If the planetary geologist is caught at the end of her world74—out of breath—having confronted Empire—with the enemy outside in the street—all the bravery in her heart at the tip of her tongue—only a stack of writings beside her—notes, letters for the people—what would they say?

-

Adam Cancryn, “HHS Funding Slashed by 30 Percent in Budget Proposal,” Politico, April 16, 2025, link. ↩

-

Jeff Foust, “Bipartisan Caucus Criticizes Proposed NASA Science Budget Cuts,” Space News, April 16, 2025, link. ↩

-

Matthew Daly, “EPA Plans to Cut Scientific Research Program, Could Fire More Than 1,000 Employees,” AP News, March 18, 2025, link. ↩

-

Alexa Robles-Gil, “Thousands Gather Across U.S. and World in Stand Up for Science Events,” Science, March 7, 2025, link. ↩

-

“Weekly Wrap Up: For Whom, By What Means, Toward What Ends?” 500 Women Scientists, April 14, 2025, link; see also “Current Actions,” Planetary Society, link. ↩

-

“Urge Your Members of Congress to Support NASA Science,” American Astronomical Society, April 2025, link. ↩

-

“AGU Joins Suit Supporting Fired Federal Employees,” American Geophysical Union, March 5, 2025, link. ↩

-

Peter J. Hotez, “The Antiscience Movement Is Escalating, Going Global and Killing Thousands,” Scientific American, March 29, 2021, link. ↩

-

Student Workers of Columbia (@SW_Columbia), “We are constantly told to put marginalized perspectives into our syllabuses, no matter the discipline. Clearly, @Columbia considers Palestinian perspectives to be an exception. As always, we stand with our workers and will fight against this egregious breach of academic freedom.” X, January 29, 2025, link; see also Sarah Sax, “In Gaza, Scanning the Sky for Stars, Not Drones,” Undark Magazine, March 2, 2020, link; and Jake Silver, “Wonder and the Life of Palestinian Astronomy,” Science for the People 23, no. 1 (2020), link. ↩

-

“Gaza Health Ministry Receives 50,000 Expired Vaccine Doses,” Middle East Eye, September 14, 2021, link. ↩

-

“Space and the Military-Industrial Complex: A Database,” Palestine Space Institute, March 2024, link. ↩

-

Jens Morten Hansen, “On the Origin of Natural History: Steno’s Modern, but Forgotten Philosophy of Science,” in The Revolution in Geology from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, ed. Gary D. Rosenberg (Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America, 2009). ↩

-

Amílcar Quijano, “Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America,” International Sociology 15, no. 2 (2000): 215–232, link. ↩

-

Zena Agha, Ahmad Barclay, and Nur Arafeh, “Mapping Palestine: Decolonizing Spatial Practices,” Al-Shabaka, January 23, 2020, link. ↩

-

Basel al-Araj, “Exiting Law and Entering Revolution” (trans. Bassem Saad), Bad Side, April 29, 2024, link. ↩

-

Maria Lugones, “The Coloniality of Gender,” Feminisms in Movement 35 (2016). ↩

-

Arpan Roy, “Is This Narrow Coastal Strip Worth All This Blood? Bassel Al-Araj on Armed Struggle in Palestine,” Focaalblog, December 12, 2023, link. ↩

-

“Manhattan Schist in New York City Parks - J. Hood Wright Park,” New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, link. ↩

-

A clay-rich soil found across Palestine and important in Palestinian agriculture. ↩

-

Calcareous sandstones in Gaza, Palestine. See Haidar S. Anan and Usama F. Zaineldeen, “Kurkar Ridges in the Gaza Strip of Palestine,” Earth Science Series 22 (2008): 139–146. ↩

-

Andrew Nahum, “‘I believe the Americans have not yet taken them all!’: The Exploitation of German Aeronautical Science in Postwar Britain,” in Tackling Transport, ed. Helmuth Trischler and Stefan Zeilinger (Science Museum, 2003), 99–138. ↩

-

M. J. Neufeld, “Wernher von Braun, the SS, and Concentration Camp Labor: Questions of Moral, Political, and Criminal Responsibility,” German Studies Review 25, no. 1 (2002), link. ↩

-

“Wernher von Braun,” National Aeronautics and Space Administration, February 6, 2024, link. ↩

-

Ralph Blumenthal, “German-Born NASA Expert Quits U.S. to Avoid War Crimes Suit,” New York Times, October 18, 1984, link. ↩

-

Bob Granath, “NASA Helped Kick-Start Diversity in Employment Opportunities,” National Aeronautics and Space Administration, July 1, 2016, link. ↩

-

Robin Williams, “Wernher von Braun (1912–1977),” Earth Observatory, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2001, link. ↩

-

Beth Ridgeway, “NASA Invites Media to 2024 von Braun Space Exploration Symposium,” National Aeronautics and Space Administration, October 23, 2024, link. ↩

-

Thandi Loewenson, “Celestial Settler Frontiers,” e-flux, March 2025, link. ↩

-

See Peter Redfield, “The Half-Life of Empire in Outer Space,” Social Studies of Science 32, nos. 5–6 (2002): 791–825, link. ↩

-

See, for example, “Hawaii Supreme Court Affirms TMT Permit,” TMT International Observatory, October 30, 2018, link. ↩

-

Al-Araj, “Exiting Law and Entering Revolution.” ↩

-

Al-Araj, “Exiting Law and Entering Revolution.” ↩

-

Sahba El-Shawa and Divya M. Persaud, “The Palestine Space Institute: Disrupting a Culture of Space Militarism, Colonialism, and Imperialism,” paper presented at the 75th International Astronautical Congress, Milan, Italy, October 2024, IAC-24,E1,2,5,x82479. ↩

-

For further discussion, see Janet Vertesi, Seeing Like a Rover (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014). ↩

-

“Over 34,000 Civilians Killed in Iraq in 2006, Says UN Report on Rights Violations,” United Nations, January 16, 2007, link. ↩

-

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OCHA), “Palestinian Death Toll Reaches 202 as ‘Operation Summer Rains’ Extends into Its Tenth Week,” Electronic Intifada, August 24, 2006, link. ↩

-

“Space and the Military-Industrial Complex: A Database.” ↩

-

See, for example, Brahim El Guabli, “Saharanism in the Sonoran,” Avery Review 58 (October 2022), link. ↩

-

“Panoramic Camera (Pancam),” PDS Geosciences Node, Western University of St. Louis, link. ↩

-

“UK Export Licences Applied For by E2V Technologies and Teledyne Technologies for Military Goods Between 2008 and 2021,” Campaign Against the Arms Trade, link. ↩

-

“Actel Delivers SX-A FPGAs Qualified to Military Specifications,” Design & Reuse, October 7, 2002, link. ↩

-

Edward W. Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Vintage, 1994), 9–10. ↩

-

For instance, the concept of “planetary boundaries,” which concerns the attempt to define the limits of Earth, such as ocean acidification. ↩

-

Thomas J. Demos, Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today (London: Sternberg Press, 2017), 1–132. ↩

-

“African Burial Ground National Monument,” National Park Service, link. ↩

-

Lisa Wade, “Modern Politics, the Slave Economy, and Geological Time,” Society Pages, July 18, 2014, link. ↩

-

Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt, “Commodified Land, Dangerous Water: Colonial Perceptions of Riverine Bengal,” RCC Perspectives, no. 3 (2014): 17–22, link. ↩

-

Usama Zaineldeen and Adnan Aish, “Geology, Geomorphology and Hydrology of the Wadi Gaza Catchment, Gaza Strip, Palestine,” Journal of African Earth Sciences 76 (2012): 1–7, link. ↩

-

Noelani Goodyear-Ka'ōpua, “On the Cattle Guard,” Biography 43, no. 3 (2020): 527–529, link. ↩

-

Sam Kriss, “Manifesto of the Committee to Abolish Outer Space,” Anarchist Library, January 21, 2016, link. ↩

-

El-Shawa and Persaud, “The Palestine Space Institute.” ↩

-

Noelani Goodyear-Ka'ōpua, “Ea and Aloha ʻāina on Mauna a Wākea,” paper presented at Space Science in Context, May 2020, virtual. ↩

-

Bawaka Collective, “Celestial Relations with and as Milŋiyawuy, the Milky Way, the River of Stars,” in Routledge Handbook of Social Studies of Outer Space, ed. Juan Francisco Salazar and Alice Gorman (London: Routledge, 2025), 217–226. ↩

-

“Speaking Up for the U.S. Scientific Enterprise – Resources, Support & Latest News,” AAAS, link. ↩

-

Harvey V. Fineberg, “Thirty Meter Telescope Benefits Humankind,” Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, April 15, 2015, link. ↩

-

“Our Donors,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, link. ↩

-

Steve Salaita, “No Resurrection: The Life and Death of the Modern University,” April 15, 2025, link. ↩

-

Erin Reed, “Opinion: England’s Anti-Trans Cass Review Is Politics Disguised as Science,” Erin in the Morning, April 18, 2024, link. ↩

-

“2021 Media Backgrounder: Wet’suwet’en 101,” Gidimt’en Checkpoint, 2021, link. ↩

-

“Elbit Systems UK Loses Its Biggest Contract with the Ministry of Defence,” Palestine Action, November 22, 2024, link. ↩

-

Al-Araj, “Exiting Law and Entering Revolution.” ↩

-

SupGaleano, “A Few First Questions for the Sciences and Their ConSciences,” Enlace Zapatista, December 26, 2016, link. ↩

-

Al-Araj, “Exiting Law and Entering Revolution.” ↩

-

Alex Aviña, host, “Why We Write w/Mary Turfah and Taylor Miller,” The East Is a Podcast, March 9, 2025, 1:15:44, link. ↩

-

Ameed Faleh, “‘A Productive Language’: On Western Intellectual Paradigms and Refaat al-Areer,” Ebb Magazine, April 24, 2024, link. ↩

-

Basel al-Araj, “Why Do We Go to War?” Palestine Will Be Free, March 8, 2025, link. ↩

-

Salaita, “No Resurrection.” ↩

-

See Makdisi Street, “‘Palestinians have the right to reject surveillance’ w/ Hadeel Assali,” March 22, 2025, 1:19:25, link. ↩

-

Nâzim Hikmet, “On Living” (trans. Randy Blasing and Mutlu Konuk), Nâzim Hikmet Archive, Marxist Internet Archive, link. ↩

-

Honoring her teacher, Basel. ↩

Divya M. Persaud is asking you to do what you can today to interrupt genocide, dismantle settler colonialism, and free Palestine. Confront the apparatus that make us co-conspirators in this death-making project. Be renewed in knowing of those who will follow.