What follows is a story of return—of my family’s journey back to their village in southern Lebanon more than a year into Israel’s systematic assault. It would be easy to mistake it for a return to the ruins of a house I had designed for them. But here return is an act of homemaking itself, a deliberate cleansing of empire’s filth, an assertion of presence that war sought to erase.

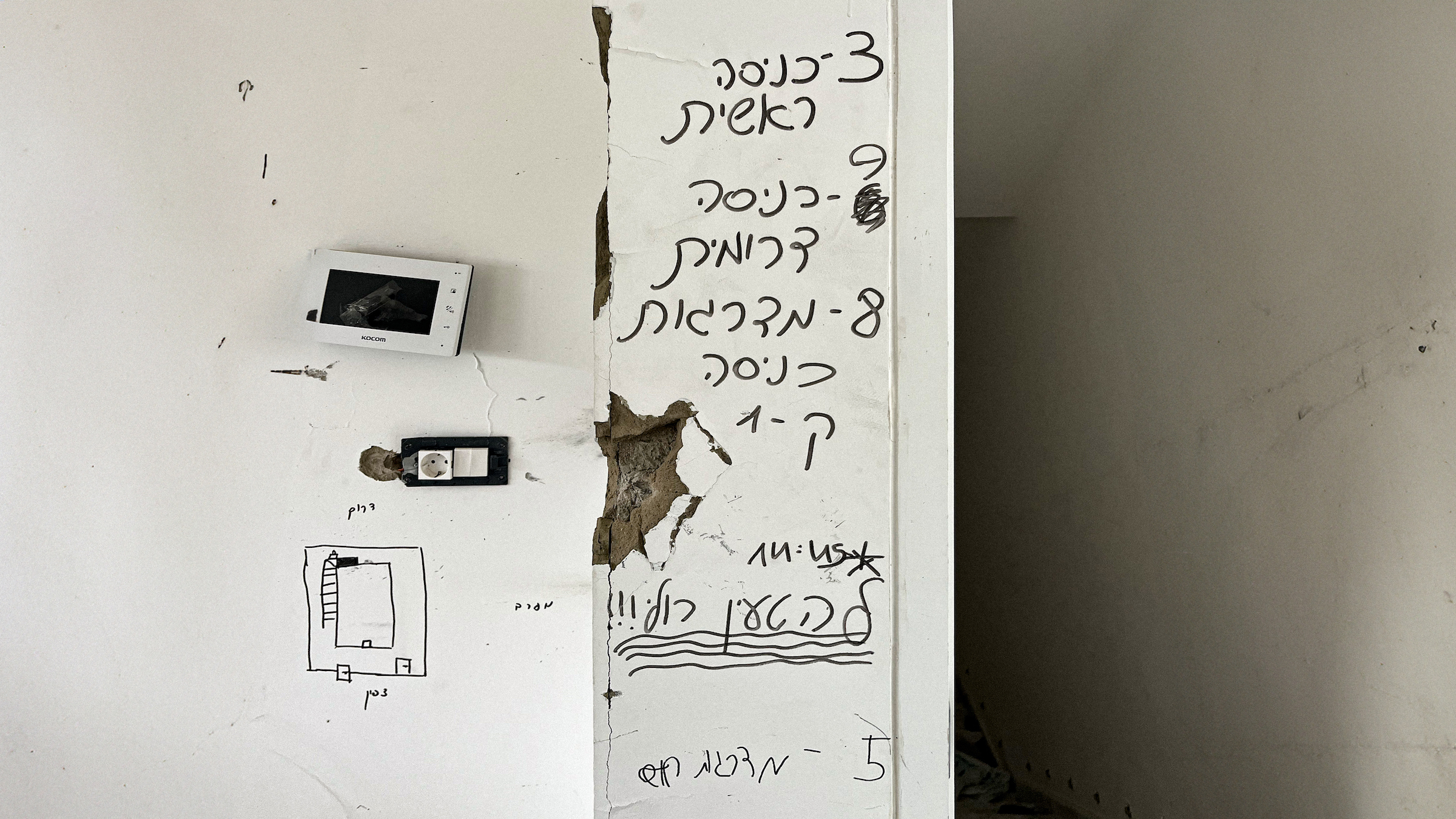

From the top of the hill, the house still stood. This alone was enough to make their breath hitch, enough to carve a moment of fragile relief into the weight of their return. It was battered, its walls pockmarked with the scars of war, but it was there. Even from a distance, they could see the gaping wounds—windows shattered, walls split, a roof slumped in parts where missiles had kissed it—but they had seen worse before and had learned to hold on to what was left. So, they let themselves feel it, the strange joy that at least their home had survived. Then, as they moved closer in the late afternoon light, that joy unraveled. The house was standing, yes, but the destruction was precise, deliberate. The front door hung half open, waiting. And then the truth revealed itself: their house had been used. Occupied. Turned into an Israeli military stronghold. Soldiers had eaten here, slept here, and mapped out their war in rooms where children had once played. They had stretched their limbs across their beds, drank from their cups, placed food on their plates, licked their forks and knives clean, all used, all defiled, all made complicit in the empire’s feast.

Then the smell hit—not just rot, not just months of abandoned food stewing in filth. Something deeper. Something meant to desecrate. Feces smeared on the beds, mounds of excrement in corners, urine soaked into the floors. It was a scene composed with intent, a performance of conquest inscribed in waste. But it wasn’t the filth that made them sick. It was the memory they would now carry, clashing with the ones that held their histories and kinships. It was the unbearable realization that they might forever sense the stain of those alien bodies, their presence clinging to every surface, like the foul messages they scrawled across the walls. The first to gag was the one who knew the house best. My aunt, the eldest, doubled over, heaving as if her body had found the truth before her mind. Then another, then another. Vomit splattered across the ground, tracing the intimacy of loss. Out came a somatic elegy, a cartography of rejection inscribed onto the floors. Bile rose where architecture collapsed, redrawing in retch the limits of what could still be called home. Their disgust was a sovereign act of designation, a declaration that presence alone does not equal belonging. And so they stood there, bent over their expulsions, their bodies speaking what their mouths could not.

Beneath the disgust simmered an anger sharpened by decades of war and displacement, an anger that refused to wait for justice to be brokered by foreign hands. And with it came questions heavier than the rubble itself: How do you overcome this repulsion for your own home? How do you confront the thought that the same settlers who dehumanize you spared your house—because they admired it, occupied it, maybe even dreamed of making it their own? It was clear that normal cleaning would never be enough. Scrubbing grime, washing floors, clearing debris; these were necessary but secondary. Even the physical remnants of war, the unexploded bombs and hidden traps designed to maim long after the fighting had ended, could be removed through the rational processes of postwar reconstruction.1 But the filth left behind was a contamination that no broom or bucket could erase: an ontological stain, settling into their belongings, into the very air. Saving home required more than rebuilding; it demanded a different kind of touch—one that, Menna Agha argues, is not about replicating possession but restoring intimacy, reclaiming space through the emotional labor of those who refuse to let it be lost.2

Before lifting even a single stone, my cousins summoned the sheikh. Dusk arrived with precision, its timing not incidental but necessary, blunting the harsh contours of ruin and signaling the beginning of cleansing. The sheikh walked the length of the house, stepping carefully over shrapnel, past piles of waste, past stains that would take weeks to scrub away. He did not touch anything, did not move what had been broken or displaced. His voice rose into the walls, amplified by the thickening darkness, filling spaces where soldiers had settled. He recited verses meant to drive out the lingering residues of their failed occupation. Where they had mapped conquest, he mapped return. Every room, every doorway, every shadowed corner was named and restored, enacting what M. Jacqui Alexander describes in Pedagogies of Crossing as a dimension of spiritual labor that renders the sacred and the disembodied palpable and tangible.3 To name the house anew was to re-situate it within a spiritual jurisdiction unrecognizable to colonial cartographies. Then they turned to the trees, carrying water as if approaching old friends. The trees had been there long before the house, had witnessed war and return, had bent under the weight of airstrikes, and had held their ground even as fire licked their branches. Some were charred, some snapped in half, some stripped bare. One by one, they watered them, not out of necessity but out of reverence. As always, they tended to them in darkness, when the night loosened the grip of the sun, when the soil could absorb rather than resist, when the land itself, weary yet waiting, was most receptive to repair. They placed their hands on the trunks, whispered apologies, and asked forgiveness. In this quiet exchange, the night did not merely conceal; it enabled. It dulled the imperial eye and sharpened their own, allowing a different kind of labor to emerge—one grounded in what darkness makes possible, not as metaphor but as method.

Inside, they took what little zamzam water they had, holy water from a distant well now poured over a home wounded by war. They moved through the rooms, careful and deliberate, letting each drop land where it was needed most. Into cracks in the floor where boots had stomped. Into bullet holes puncturing the walls. Along edges of rooms where missiles had torn them open. A drop here, a drop there, held longer by the coolness of the night. As darkness stretched further, another act of cleansing began. They lit the bakhoor. At first, the scent curled hesitantly into the air but then thickened, expanded. Shadows swallowed the scars of war as the fragrance wove through every corner, filling the cracks, twining around the remnants of occupation. The night obscured, the smoke purified. Later, they scattered plastic chairs around the remnants of their house. They kindled a small fire that drew Israeli drones like mosquitoes to light, and they sat with neighbors as stories of shattered homes and interrupted lives moved softly among them. The warmth of the fire pushed against the cold, against the wreckage. As midnight approached, their voices rose into the night, speaking a language no invader could erase, a grammar that, as Leanne Betasamosake Simpson reminds us, is rooted in the native land and unshaken by the logic of the settler state.4 To gather in the dark was not to disappear but to choose a visibility ungoverned by military recognition. This was the final act of cleansing—framing return not as the end of destruction but the beginning of collective healing. Their act was architectural in the most radical sense: a praxis of recovery enacted on their own terms, not as a return to what was but as a refusal to let occupation define what comes next. This refusal was not new to them; they had already practiced it on this very soil.

Fifteen Years of Return

Less than a week before the end of the 2006 Lebanon War, on August 8, my aunts were huddling in the corner of their stone house when the shells began to rain down. They had trusted the thick walls our ancestors had quarried and stacked. But a certainty settled in their bones: the next strike would not miss. There was no time to think or gather anything. They ran to the sputtering car, hands fumbling with the key, breath locked in their chests. As they turned the corner, the blast hit. The ground convulsed, the car jolted forward, windows shattered, glass and dust whipping through the air, stones pelting them, shrapnel from a home unmade. By the time they reached the top of the hill, smoke had swallowed everything. For a moment, they saw nothing. Then, through shifting breaks in the dust, they caught glimpses of what was no longer there, a shape described by its absence, what Avery Gordon calls the paradox of haunting.5 One of my aunts looked at the clock on the car’s shattered dashboard—2:45 pm. The exact moment their home ceased to exist. And in that instance, as they looked back at the emptiness, they encountered a violence so complete, so indifferent, that it exceeded anything they had known. They had feared war, they had understood its brutality, but they had never imagined the depth of the empire’s hunger, its ease in unmaking their world in seconds.

A year later, once Israel’s cluster munitions had eased their grasp on the land, my aunts returned. It was afternoon when they arrived, the same hour they had fled. The smoke had lifted, but the wreckage remained: stones hurled into heaps, walls burst open, and dust settled where a home had once stood. No one left that night. They sat around the ruins as darkness fell, their voices hushed, tracing the outlines of what was lost, what could never be recovered, and what remained. They did not come as spectators nor as mourners. Like the Poets of the South, who, in Yasmine Khayat’s words, reinterpreted the classical Arabic tradition of ruin gazing—al-wuquuf ‘ala al-atlal—they returned to witness, to confront the devastation wrought by Israel.6 But they were not Poets with a capital P. They were the poets under the stone and the writers in the shade of the olive tree, as the famous ‘Amili proverb reminds us.7 And so, each year on August 8, at exactly 2:45 pm, all forty of us would return to the ruin, gathering through the night around a fire. The elders sat close to the flames, their faces etched with the weight of what they had witnessed. For us, the younger ones, the night became our school, veiling the wreckage before us while etching its makers into our minds. We sat cross-legged on the ground, the fire’s heat on our faces, the cool dark pressing our backs. Wide-eyed, we listened as they spoke of wars that neither began nor ended with the violence that shattered our walls. The rubble remained for fifteen years, not because it could not be cleared but because to remove it too soon would have erased the memory it carried, the memory that shaped us.

By the fifteenth year, a quiet sureness had settled. The time had come to clear the rubble, to rebuild, to gather again on the land that had carried us for generations. The following year, we returned—not just to witness but to work. Hands that had once sifted through ruins now gripped shovels and pickaxes. The youngest carried small trowels, their fingers still learning the weight of stone. The older ones hauled sacks of debris, their backs bent under the labor of removal. The elders, who had spent years watching over the ruins like guardians, guided the process. The work was slow, deliberate, each lifted stone an act of reclamation. And then, as if waiting for its moment to be seen, the land revealed what had endured beneath the ruins. We uncovered, or perhaps the proverb had chosen for us, a single terrazzo stone, unbroken, the same kind that had once lined the floors of the old house. Beside it, a lone olive tree, the only survivor of a grove that had once stretched across the land. The others had been burned to their roots by the white phosphorus Israel had rained over the soil, yet this one had been spared, paradoxically, because of the rubble. As each stone was lifted, it became clear we were not removing the old house but building the new one. Purging the colonial war machine, from one’s mind and land, is itself reconstruction. And so, when I was entrusted with planning our new home, the aim was never to build anew but to manifest a collective unbreakable space that had been unfolding for several years.

To imagine this home was not just to decide what to build but to confront what it means to build at all after destruction. In the face of an imperial arsenal that annihilates with both precision and reckless abandon—the very lifeblood of a settler state propped by Western interests—construction is always fragile, and always under threat. But a stone laid in defiance holds more weight than any blueprint drawn in submission. Architecture, after all, can be more than walls and roofs; it can be a cyclical practice, a continuous act of rehearsing, affirming, and enacting the right to land, to presence, to life that refuses erasure. To build is not only to shelter but to insist. So the house took shape around what had refused to die. The olive tree, once buried beneath the rubble, now stands at its core, its roots gripping the earth, its branches stretching over the smaller dwellings contained within. It is where families gather, because only gathering can fortify a home that lives beyond walls. Beside it, the terrazzo stone lies embedded in the shared hall, unnoticed for most of the year, until a single ray of light illuminates it at exactly 2:45 pm on August 8. Before the light strikes, we push the furniture aside and sit on the floor, gathering as we once did around the rubble, a union that starts in daylight and lingers into the night. These are not gestures of nostalgia. They are intentional, material acts of space-making—assertions of an architecture that no missile can unmake. And in this work, those most affected by settler colonialism do not merely survive; they shape the foundations of a decolonial future, one in which they are not peripheral or incidental, but indispensable.

These acts of collective insistence—of building and rebuilding around the stone and the olive tree, of passing down not property but an unrelenting pursuit of freedom and life—made this home worthy in the eyes of those who sustained it. Its value lay in its capacity to hold memory, anchor people to their land, and make a future imaginable. But what was invaluable to its caretakers meant something else entirely to its occupiers. To them, it was never a home but a prize to be seized, inscribed with their names, defaced with promises to their families across the border. They spared it not out of reverence but because it served their colonial imagination. This is the perverse logic of white supremacy: Worth is measured not by rootedness in life but by legibility to power. Homes that failed to register in that imperial gaze, like those of our neighbors, were erased, deemed unworthy of preservation or existence itself. To be seen is to risk being seized, repurposed, or instrumentalized. To remain unseen is to risk annihilation. This is the logic of empire wherever it extends itself, from the battlefield to the university. After all, the Zionist soldiers did not occupy our house as a matter of military strategy but as agents of a value system shaped by Western institutions—institutions that wield the same weapons to silence dissent and dictate who belongs and who must be cast out. This is mine to reckon with: that the shell of the house, which mattered to me far more than to my family, endured not in defiance of imperial greed but because of it, appealing both to the institutions I granted the power to determine the worth of my work and to the settlers who claimed this work as their own. This is the buried relationship between academia and practice, too often obscured by the assumption that bridging the two is inherently virtuous. Yet here is one such bridge, realized in the flattening of the house into this essay, and in the possibility that this very essay may one day flatten the house for good.

Darkness and Disgust

To claim is to contaminate. Such was the visceral shock of return to a home caught between possession and estrangement, neither fully theirs nor wholly ours.8 It stood in a state of defilement, corrupted by the proximity of their bodies, bearing the imprint of their routines, their sweat, their piss. Empire has long wielded disgust as an instrument of power: pathologizing racialized bodies, segregating space through “hygienic” regimes, framing resistance itself as a contaminant, a threat to purity.9 The scholarship on this is vast, yet too often it assumes that the colonized are only ever the objects of this revulsion, that they alone are positioned to be seen as soiled, never as ones who recoil in disgust. This omission flattens the sensory politics of oppression, overlooking the bodily rebellion against empire—one that erupts not as a metaphor but as a physiological revolt, an uncontrollable expulsion. Vomiting upon encountering the occupied house was not just a symptom of distress; it was the native body’s rejection of imperial intimacy, a refusal to incorporate the residue of its presence, to metabolize its claim. It was the stomach wrenching itself away from the violence of conquest, a gut-deep defiance that preempted thought or language. In The Performativity of Disgust, Sara Ahmed describes how “the proximity of the ‘disgusting object’ may feel like an offence to bodily space, as if the object’s invasion of that space was a necessary consequence of what seems disgusting about the object itself.”10 To gag at the house was precisely this—an encounter with the unbearable nearness of white supremacy, an unmediated rage at the way its claim had rearranged the order of things. Disgust is not mere repulsion; it is a sensory insurrection, an immediate and involuntary resistance to domination. It does not argue, negotiate, or strategize. It does not take time to consider what is possible. It simply rejects. And in its raw, convulsive rejection, it stages the most absolute refusal of all.

Disgust, like grief and anger, demands its own space-making practices, ones that remain unseen by those who are themselves the objects of that disgust. To the Israeli drones patrolling the night sky over south Lebanon, scanning the landscape with the detached precision of satellite imagery, the world appears as a stark binary: darkness and light, absence and presence, civilization and wilderness. Conditioned by the ideological machinery that has long harnessed the cosmos in service of colonial conquest, their perception is as rigid as the epistemologies that sustain it. They see themselves as the source of illumination, casting their radiance upon the obscurity of those they deem formless, archaic, or subhuman. Yet they fail to see how the night, long reviled for its ungovernability, conspires with the so-called abject to stage acts of renewal and refusal—refusal of a light that names, frames, and classifies. As Momtaza Mehri writes in I See That I See What You Don’t See, “For those who seek to reduce the suppleness of human relations and possibilities into rigid taxonomies, darkness is stubbornly difficult to pinpoint and contain. Depending on who you ask and when, it is both exciting and repulsing. Darkness precedes and exceeds the frame; it lubricates the machinery of collective mythmaking.”11 Especially now, as I write, families gather in the ruins of their homes, assembling in scattered pools of light that defy destruction and occupation. The night amplifies their work: deepening the echoes of invocation, magnifying the healing power of water, erasing visible wounds, and drawing people together in a shared commitment to life. Settler colonialism, which designates certain bodies, lands, and ecologies as waste, finds itself expelled by the very forces it has sought to render uninhabitable. What was meant to fester in abjection instead becomes a terrain for survival, a choreography of resistance, a space where colonial greed is exorcised. In the nocturnal hours, when the occupier’s gaze falters and the logic of surveillance is betrayed by its blindness, new forms of life emerge—forms that neither seek nor require recognition from those who have long mistaken their violence for illumination.

Thinking with the night means confronting architecture’s role in the face of colonial expansion not only as a practice of repair or reconstruction but as one of purging. Now, as the empire rots faster than it can sustain itself, as the stench of its decay seeps into every crevice, the urgency is not only to document its collapse but to ensure that its remnants do not settle into the spaces it once claimed. The night offers no monuments, no blueprints, no gestures of recognition. It offers the tools to cut through what lingers, to suffocate the traces of power that refuse to die, to make architecture not a site of survival but a battleground for sovereignty. This was never clearer than on the first night of Suhoor under the short-lived cease-fire in Gaza, a deal that took effect in January 2025 and was violated by Israel just two months later. The Omari Mosque, its walls scarred by shrapnel, its dome hollowed by fire, filled once more with bodies standing shoulder to shoulder for the first Tarawih prayers in over a year of genocide. Makeshift wooden and nylon columns braced what remained, but it was the congregation that gave the mosque its structure. Their voices rose through the open ceiling, through wounds in the stone, through air that for the first time in months was not thick with fire and dust. Outside, strings of Ramadan lights clung stubbornly to whatever could hold them. Children gripped their lanterns tightly as they walked through the streets, their faces flickering in the glow. In Khan Younis, the musaharati was not alone. His drumbeat echoed through the ruins, a pulse in the dark, as a crowd moved with him through the shattered city. They stepped over broken stone, past tents where the displaced lay curled under thin blankets. Banners stretched between crumbling walls, lanterns swayed from wires, and in the hollowed-out shells where homes endure beyond their destruction, families gathered however they could, reclaiming and remaking.

They are the only constellations that matter—the true guiding stars, the ones who refuse erasure, who defy the billions spent on their annihilation. Their light is not the cold gleam of conquest but the glow of gathering, of those who return to ruins as both mourners and makers, who sit in the hush of destruction and call the land by name. They do not seek validation in the gaze of power; they move beyond it, severing its grip, turning its filth into fuel. They know the night is not emptiness but abundance, a horizon where dominion unravels and a world otherwise begins. To consider the night’s power to strip empire bare is not just to stand with them in their fight for life, in the darkest hours when their defiance burns brightest, but to take up their disgust, to wield it, to let it fester and spread until every false star collapses under its own rot. Disgust at the blue stars raining fire from the sky, burning bodies and futures into ash. Disgust at the fifty white stars, gnawing, swallowing, demanding more. Disgust at the twelve golden stars orbiting in perfect formation, calculating, waiting to feast. Disgust at the stars that link empire to empire, mapping conquest from above, wiring the planet into submission. Disgust at the metal-plated stars gleaming from the chests of those who wait, who watch and pull the trigger. Every last one of them, sigils of conquest, bright insignias of destruction, carved deep into uniforms and treaties and corporate logos, all shining with the blood they spill. Let the night rise, let it stretch and consume, let it leave nothing but silence where they once gleamed.

-

See Jasbir K. Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). ↩

-

Menna Agha, “Emotional Capital and Other Ontologies of the Architect,” Architectural Histories 8, no. 1 (December 18, 2020): 23, link. ↩

-

M. Jacqui Alexander, Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005), 7, link. ↩

-

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017). ↩

-

Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 6. ↩

-

Yasmine Khayyat, War Remains: Ruination and Resistance in Lebanon (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2023), 34. ↩

-

“Under every stone, a poet; and in the shade of every olive tree, a writer.” ↩

-

In a recent piece, “Umm Kamel’s Affair,” I explore a similar condition of hybridity—one in which the Israeli drone, rather than being expelled, is reabsorbed into the social and mythical fabric of Jabal ‘Amil through the legendary figure of Umm Kamel, a matriarch who comes to embody the drone itself. There, the apparatus of surveillance is not destroyed but transformed, its violence alchemized through cultural production into a vessel of indigenous cosmology. See “Umm Kamel’s Affair,” Journal of Architectural Education 78, no. 1 (2024). I trace this logic further in “Worlding in the Brightness of Imperial Savagery” through the white locust—an epistemic figure born of the white phosphorus scattered by Israel across the soil of southern Lebanon. The house, too, bears the mark of this entanglement. But unlike Umm Kamel and the locust, which arrive from the sky and cannot be fully unmade, the house is a structure rooted in ancestral ground. And so, while all three are the offspring of colonial violence and native worldmaking, it is only the house that can be fully purged. See “Worlding in the Brightness of Imperial Savagery,” The Funambulist 57 (2024). ↩

-

See, for example, Matthew J. Wolf-Meyer, American Disgust: Racism, Microbial Medicine, and the Colony Within (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2024). ↩

-

Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, 2nd ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 86. ↩

-

Momtaza Mehri, “Provocations on Shadow Play,” in I See That I See What You Don’t See, ed. Marina Otero Verzier and Francien van Westrenen (Rotterdam: Het Nieuwe Instituut, 2020), 329–342. ↩

Mohamad Nahleh is Assistant Professor of architecture at The Ohio State University. His research and practice, Nightrise, engage the fields of environmental history, cultural anthropology, and postcolonial literature in expanding the role and imagination of the night in architecture. Nahleh holds a Bachelor of Architecture from the American University of Beirut and a Master of Science in Architecture Studies from MIT.