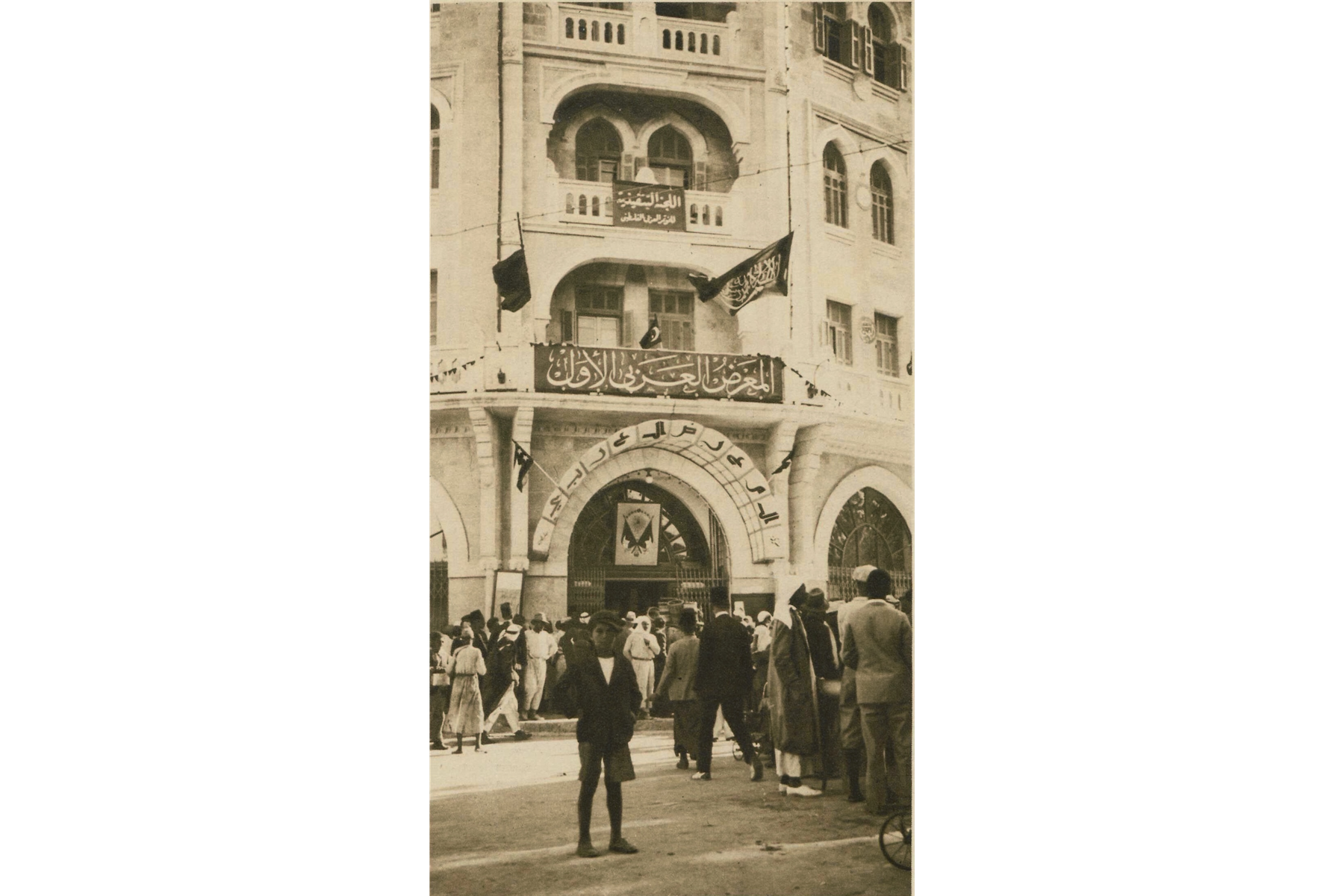

In July 1933, a large crowd from all over Palestine and even some neighboring Arab cities, gathered in Jerusalem in front of the Palace Hotel to attend the First Arab Exhibition. The exhibition—along with its second installment in 1934—sought to showcase and promote the latest Arab innovations, industries, products, crafts, and arts. Walking through the hallways of the Palace Hotel and into its rooms—which were repurposed as exhibition spaces—one would have found chocolate from Beirut, cigarettes from Haifa or Latakia, fragrances from Tripoli, soap from Nablus, blankets from Baghdad, leather works from Aleppo, carpets from Cairo, silk and cotton fabrics and garments from Damascus, Tatreez embroidery, and mother of pearl pieces from Bethlehem, as well as many other products from the Arab world, like oil paintings, metal works, furniture, and medicine. If visitors got tired walking around the exhibition halls, they could rest in the building’s garden cafe or attend a cinema screening or music performance in its theater on the upper floor. The Palace Hotel was not only the site where the exhibitions took place; it was itself on display in a way. Built in 1929 by the Supreme Muslim Council, it was a sign of Palestine’s modernity, and itself was one of the local innovations the Arab Exhibitions sought to celebrate.

In June 2024, a crowd gathered in Amman at Darat al Funun to attend Resurgent Nahda: The Arab Exhibitions in Mandate Jerusalem1—an exhibition curated by architectural scholar Nadi Abusaada that sought to shed light on the history of the First and Second Arab Exhibitions that took place in Jerusalem in 1933 and 1934.

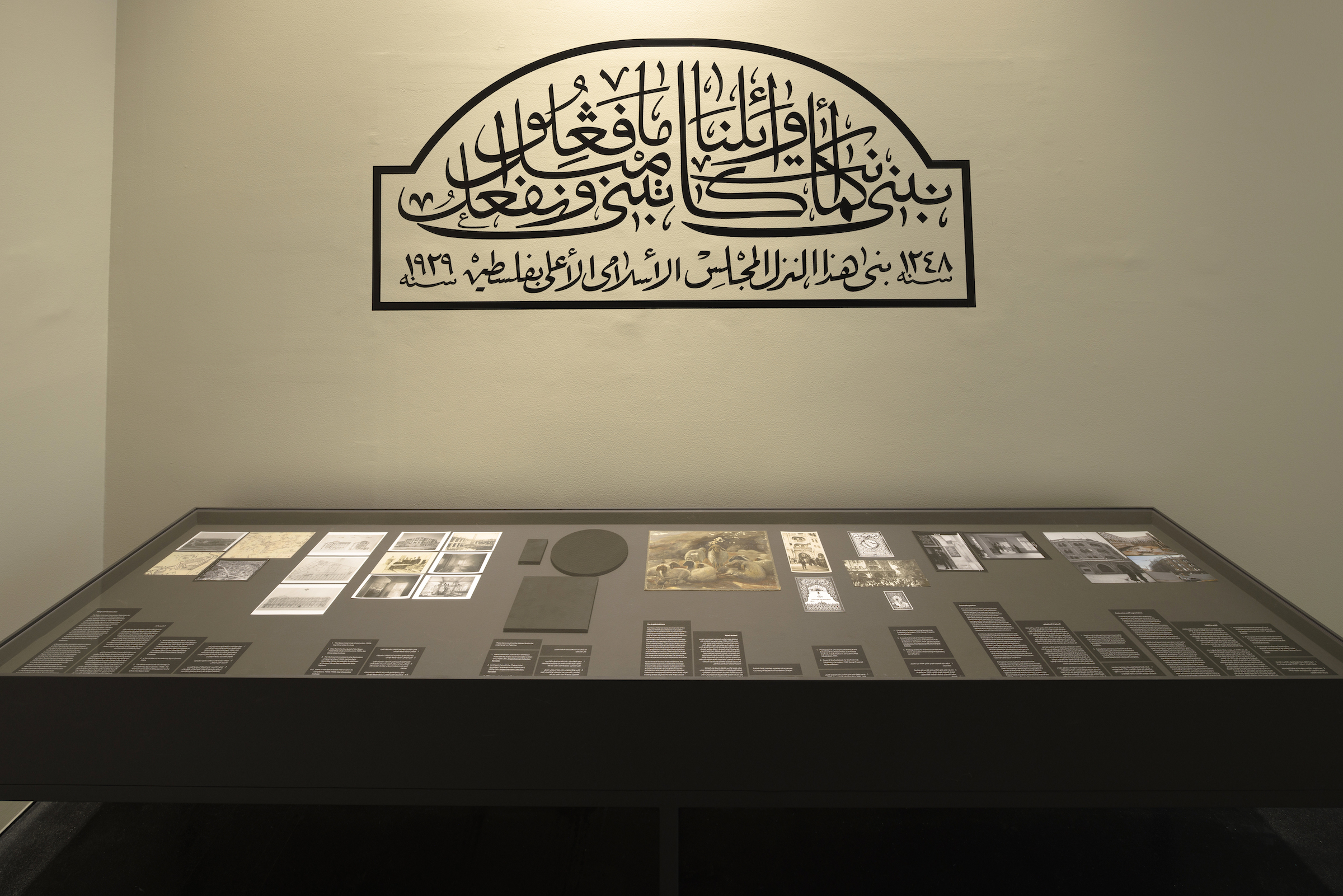

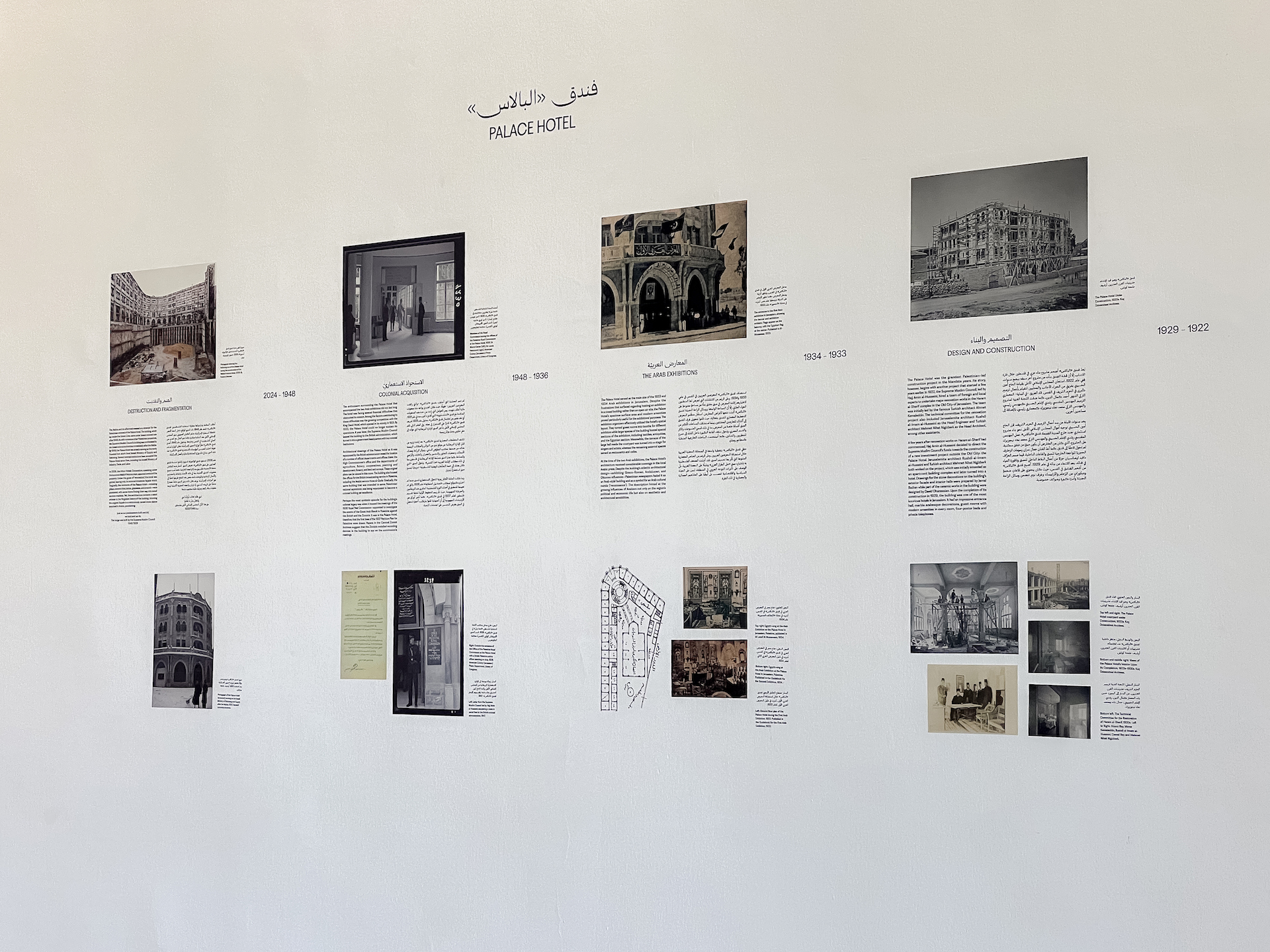

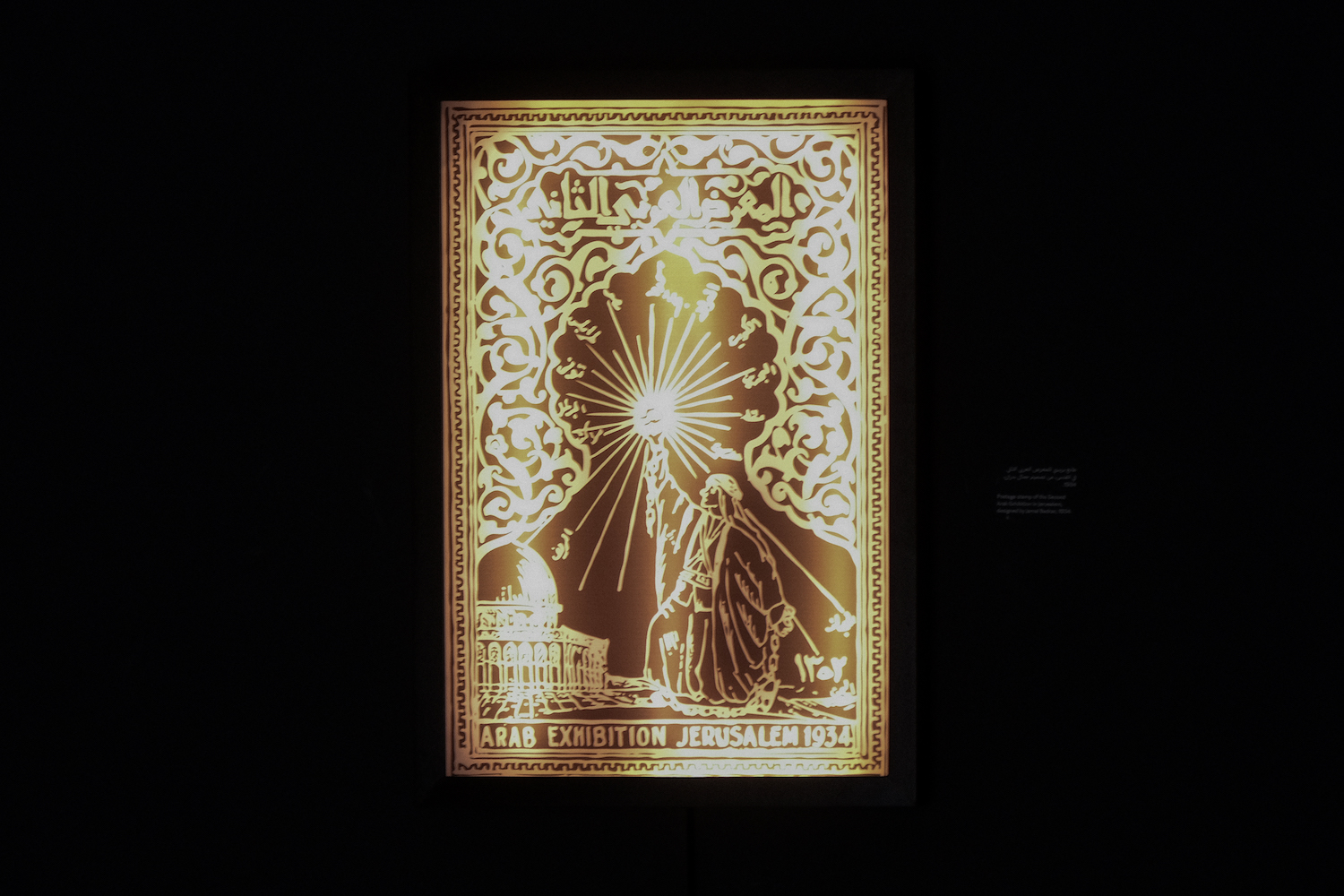

Resurgent Nahda consists of three main sections. The first lays out the historical context in which these events were organized, asking: How did they come to be? Who was behind them? How were they influenced by other regional and international exhibitions? And where do they fit within the bigger picture of the Palestinian national movement and struggle during the British Mandate? The second is dedicated to the artists, artisans, and craftspeople whose work was featured in the Arab Exhibitions, showing paintings by Nicola Saig, Zulfa Al-Sa’di, Khalil Halaby, and Sophie Halaby; glass vases and illustrations by Jamal Badran, who is credited in the wall text as the chief illustrator for the exhibitions; embroidery pieces by Nijmeh Kharoufeh and Mary and Jamila Salman; and mother of pearl works by Yousef al-Zughbi. The third section focuses on the architectural fabric of Mandate Jerusalem. It shows the blueprints of the Palace Hotel and outlines the tragic post-history of the building.

One could choose to view Resurgent Nahda as an exhibition documenting a specific moment or event in the history of Mandate Palestine. But doing so, I believe, overlooks a crucial aspect of the exhibition. Instead, I propose engaging with Resurgent Nahda as a meta-exhibition—an exhibition about exhibition-making practices—one that both explores and propels exhibitions as sites of imagination. I argue that Resurgent Nahda illustrates how the domain of exhibition-making became a battleground for contradictory colonial and Arab national social imaginaries in Mandate Palestine, at the same time that it mobilizes the audience’s imagination in countering colonial erasure through curatorial experiments in speculative and potential history.

Negative Objects and Imagined Exhibitions

Resurgent Nahda is the second exhibition that Abusaada put together on the same topic. In 2022, Abusaada, in yet another meta-exhibitionary move, mounted Al-Ma’rad (Arabic for “the exhibition”) in the Khalil Al-Sakakini Cultural Center in Ramallah.2 I have not attended either rendition of the exhibition that I review here, but I was taken on multiple virtual tours of them, which inform this review. When I visited Darat al Funun in May 2024, the exhibition space was still empty. Workers were repainting the walls in preparation for the installation. My partner Zaina Zarour and I met with Abusaada and assistant curator Tala Alhaj to deliver ten postcards from our collection, designed by artist Sophie Halaby in the 1950s, which were included in the show. Abusaada then offered to give us a tour of the yet-to-be-installed exhibition. He pointed at a blank, newly painted wet white wall and explained, half-jokingly: “Here you can see the exhibition’s title and wall text.” Abusaada took us on an elaborate tour. He explained the different sections of the show and described in detail the objects that would be shown and the method in which they would be displayed, while pointing at different parts of the empty space or making gestures to help us imagine various objects.

This tour of an imaginary exhibition reminded me of the research display that Abusaada showed at Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai as part of the 2023–2024 exhibition Guest Relations.3 The display was an adaptation of a chapter from Al-Ma’rad that focused mainly on the Palace Hotel. In this installation, Abusaada displayed archival documents and photographs of the building and the exhibitions, as well as a damaged painting by Zulfa Al-Sa’di. But what was most striking to me were the three pieces of bare black foam placed at the center of the display. The caption beside them read: “These items could not be shipped due to the ongoing war on Palestine.” The three pieces of foam were supposed to hold a wall tile from the hotel designed by renowned ceramist David Ohanessian in addition to an ice cream cup and a white plate on which the hotel’s name is inscribed. These three objects were not simply absent: Through the insertion of the black foam pieces and the captions, they were present as negative objects.4 Abusaada was pointing at the void and telling us, “Here you can see a tile, a cup, and a plate. Here you can see a hotel.”

Abusaada could have simply decided to remove the three objects from the display. He could have shown images of them. His choice, however, to exhibit them as negative objects renders their absence integral to the installation—not only their absence due to the ongoing war on Palestine but also a reminder of the displacements within the objects: the tile, the cup, and the plate were plundered among other remnants of the Palace Hotel before reappearing in Israeli auctions and finally finding their way back to private Palestinian collections. In the words of Walter Benjamin, the effect that these objects have on their audience “does not rest in an encounter with the work of art5 alone but in an encounter with the history which has allowed the work [in this case, prevented the work] to come down to our own age.”6 Moreover, the negativity of these objects prompts and demands the imagination of the viewer for its negation. The pieces of foam holding the void call on the audience to visualize what the missing objects might have looked like. The objects are made positive and present through speculation and imagination.

Resurgent Nahda utilizes a somewhat similar technique, especially in the arts and crafts section. While it displays objects created by artists and artisans who were part of the Jerusalem exhibitions,7 those objects are not necessarily the same as the ones exhibited in the 1930s. This is in part because although Abusaada’s research uncovered a comprehensive list of the exhibitors, we do not yet know the exact objects that were on display. It is also due in large part to the fact that many of the objects from the Palace Hotel today are missing as a result of the long history of ethnic cleansing and colonial plunder and obliteration in Palestine that has rendered many objects destroyed, looted, lost, or unidentifiable. For many of the artists who participated in the Jerusalem exhibitions, there is not a single known example of their work.8 We know virtually nothing about these artists but their names. They exist only in the negative form.

This dynamic of loss and dispersion, which has made Palestine’s art history only possible as a history of fragments,9 inevitably confronts every historian of Palestine and its art.10 In some cases, the absence of documents and objects necessary to narrate the story of Palestine’s visual art before the Nakba fed into the fallacy of an argument from silence. This absence did not only result in an untold or inaccessible story; rather, it has also justified the claim that there is nothing to tell and nothing to know—that there was no (fine) arts scene in Palestine prior to 1948. No artists, no exhibitions, no artworks, no collectors, no market… nothing.11

In researching and exhibiting the story of the 1930s Jerusalem exhibitions, Abusaada deals with the dual question of how to write history without documents and how to curate an exhibition without objects.12 He responded by appropriating Israeli resources and archives: Abusaada retrieved the guidebooks of the exhibitions from the National Library of Israel where they were cataloged as part of the collection of looted Palestinian books and labeled “Abandoned Property.”13 There, almost like collecting fragments, Abusaada sat and took multiple detailed screenshots of a document that he was not allowed to remove from the library. He then stitched these fragments together to reformulate the document. Beyond the colonial archives, Abusaada also turned to Palestinian private collections scoping for objects that help narrate this fragmented history and translate his research into an exhibition. The rich art and material culture collection of researcher George Al-Ama was key in this regard. Abusaada also became an amateur genealogist in the process, tracing the descendants and relatives of those who were part of the exhibitions in the hope of adding another piece to the puzzle.

And yet, despite the research acrobatics needed to assemble the fragments, absences persisted. Curatorially, Resurgent Nahda embraces this absence as an integral part of the story instead of treating it as a hindrance to the show’s narration. It mobilizes the audience’s imagination to fill archival gaps and the void created by the missing objects. But imagination here is not required to “develop” negative objects into positive ones but rather to construct a truthful—albeit not necessarily factual—image of the Jerusalem exhibitions.

The discrepancy between the truth and the fact is a matter of power. A truthful narrative of the past is not simply the same as what can be established as a fact. The fact emerges only through a specific kind of evidence that is accepted within the modern discipline of history and its traditions. Palestinians are denied access to this kind of proof. Take the historiography of the Nakba as an example. Palestinians’ oral history accounts are considered less valuable, less accurate, and less credible than the writings of the New Historians14 who rely on Israeli archives.15 But when it comes to writing the history of ethnic cleansing during the Nakba, what difference does it make whether 150 people were killed or only 122? Palestinians, who are denied access to the documents of their killing and expulsion, have the “wrong” kind of evidence of the massacre. Their blood is never a good-enough proof. Their voice is suspect. Sometimes, a fact is a weapon drawn to devalue the truthfulness of the massacre. Western suspicion of and hysteria over the factuality of the death toll from the ongoing genocide in Gaza and doubting the credibility of Palestinian voices is another case in point.

Whether or not Nicola Saig’s painting The Surrender of Jerusalem,16 which was displayed in Resurgent Nahda in Darat al Funun, was indeed one of his paintings that hung in the Palace Hotel in 1933 cannot—for the moment at least—be confirmed. But it is irrelevant to the truth of the narrative. Resurgent Nahda is not a literal re-creation of the Jerusalem exhibitions, and it need not be. It asserts an image of the Jerusalem exhibitions that can only be grasped through the audience’s imagination. It invites the audience to an endeavor of speculative history. This—as Abusaada has repeatedly noted in our conversations—is not a lazy call to abandon the daunting task of research. It is a mode of documentation where the truth is as valuable as the fact.

Exhibitions as Social Networks

Another reason why it does not matter whether Saig’s painting was, in fact, part of the Jerusalem exhibitions is that Resurgent Nahda seeks not solely to reconstruct the exhibition as an event but to bring to life the multiple sub-trajectories of the Nahda for which the exhibitions were a point of intersection.

Exhibitions are usually thought of as landmark events. They are in many ways a departure from the everyday. Although the Arab Exhibitions in Jerusalem were indeed landmark events, Resurgent Nahda does not reintroduce them as such. Instead of limiting its temporal scope to the exhibitions as historical events, Resurgent Nahda foregrounds and traces the evolution of the social networks that came together in the Jerusalem exhibitions. These networks are woven from the various social forces that carried the Nahda project in different domains. The Arab Nahda, which literally translates to the Arab renaissance or awakening, is usually understood as a—primarily—literary and intellectual movement that developed in centers like Cairo, Damascus, and Beirut, starting from the nineteenth century, and that was essential to shaping modern Arab subjectivity.17 Resurgent Nahda expands this understanding and focuses on the economic and artistic networks and manifestations of the Nahda during the second quarter of the twentieth century in Jerusalem, a city not commonly considered central to the Nahda.18

These networks are reflected in the layout of the exhibition. One side foregrounds politicians, business owners, merchants, bankers, journalists, and intellectuals. Through texts and archival material detailing the exhibitions’ planning, public reception, and media coverage, it speaks to the social formation of Palestinian elites during the Mandate period and how they negotiated the organization of the exhibitions. Another corner is focused on architects and engineers through a comprehensive biography of the Palace Hotel. This display pays tribute to Rushdi al-Imam al-Husseini, the head of the Technical Committee responsible for constructing the hotel, and highlights his social role in the Association of Arab Engineers, established in 1936, two years after the Second Arab Exhibition.19

Similarly, the works of artists, iconographers, artisans, calligraphers, and designers are highlighted throughout the exhibition space, with one corner displaying the works of Iraqi artists who took part in the 1932 Baghdad Agricultural and Industrial Exhibition that hugely influenced the Jerusalem exhibitions. Among them is sculptor Fathi Safwat, whose works were exhibited in the First Arab Exhibition in 1933. References to the Nahda are tactfully placed outside the exhibition space, facing the city of Amman. Approaching Darat al Funun’s entrance, visitors are welcomed with calligraphy on the building’s façade that reads: “Love of one’s homeland is part of faith.” This phrase, which was the motto of Al-Jinan, a magazine founded by the prominent Lebanese Nahda intellectual Butrus Al-Bustani in the 1870s, was first calligraphed on a banner dropped from one of the balconies of the Palace Hotel during the Second Arab Exhibition in 1934.

Conceptualizing exhibitions as a point of intersection for various social networks means, among many things, that one is no longer bound to the time and space of the actual event. Instead, more emphasis is put on how these networks emerged and evolved around the exhibitions that brought them together. By mapping the social networks entangled in the Jerusalem exhibitions, Resurgent Nahda speaks to a relatively long period that starts with the last breaths of the Ottoman Empire and extends to follow the afterlives of the Nahda’s social networks. Similarly, it speaks to a geography in which Jerusalem became the heart of a political body that extended from the Arabian Peninsula to Morocco, with particular emphasis on the intellectual, economic, and political connections that Baghdad, Damascus, and Beirut had with Jaffa and Jerusalem. Abusaada’s tracing of these networks led him also to 1931 Paris, where the idea of the Arab Exhibitions was first conceived.

Paris and Tel Aviv / Baghdad and Jerusalem

The first thing one sees as they enter the main exhibition hall at Resurgent Nahda—even before seeing the exhibition wall text—is a historical timeline that places the Arab Exhibitions between two key revolutionary moments in Palestine: the 1929 Buraq Revolt and the 1936 Great Revolt. The timeline highlights key moments in the organization of the Jerusalem exhibitions and situates them in relation to three other regional and colonial exhibitions: the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition, the 1932 Baghdad Agricultural and Industrial Exhibition, and the 1932 Levant Fair in Tel Aviv. Abusaada presents these three exhibitions and how they influenced the Jerusalem exhibitions from the point of view of Issa al-Issa, a prominent Palestinian intellectual and journalist and the main figure behind the conceptualization of the Arab Exhibitions. The timeline quotes from al-Issa’s memoirs: “It was [during my visit to the Paris Colonial Exposition]… that my idea of holding an Arab exhibition in Palestine crystallized.”20

By framing the Jerusalem exhibitions in relation to these regional and colonial events, Abusaada paints an image in which the domain of exhibition-making was understood by al-Issa and other Nahda figures as a knot in the clash of contradictory social imaginaries: that of British and Zionist colonialism and that of Palestinian Arab Nahda. 21

In March 1932, al-Issa wrote an article titled “The Palestine Pavilion in the Paris Exposition and the Levant Fair in Tel Aviv” in the Filastin newspaper, which he cofounded.22 In the article, al-Issa shows how the Palestine Pavilion at the Paris Colonial Exposition, which was modeled after Rachel’s Tomb,23 promoted a fantasy of colonial progress and an image of Palestine as a Zionist utopia in the making. It portrayed “the extent of the success achieved in building the Jewish national homeland.” He writes:

The first thing one sees when entering the [Palestine] pavilion is an enlarged picture of Lord Balfour24 on their left... then wooden lists showing what each country paid to the Jewish National Fund... then a statement of the Keren Hayesod [The Foundation Fund], which is the fund that finances the colonization of lands purchased by the Jewish National Fund…

There is a plaster model of the Rotenberg electricity generators in Tel Aviv, Tiberias, Haifa and the Jisr al-Majami’... Then, there are drawings of the Haifa cement factory company and samples of its products. Then pictures of Tel Aviv from various angles portraying how it was before it was built and what it has become today. 25

Al-Issa notes how the visitors of the exhibition are confronted with a juxtaposition that indexes colonial superiority. It presents the Zionist movement as a modernizing force in a primitive society, emphasizing the products of the colonies and, on the other hand, disregarding the presence and products of local Palestinians. Al-Issa concludes that the Levant Fair, which was set to open a few months later, is yet another colonial exhibition that promotes a similar discourse and therefore should be boycotted.

The effect of colonial superiority that the Palestine pavilion at the Paris Colonial Exposition projects onto its visitors relies on a set of juxtapositions formulated through the inter-iconicity that emerges among the carefully chosen and curated objects on display. This inter-iconicity constructs an image-sequence: a before-and-after image that supports the modernization claim of colonialism. Perhaps the clearest example of the image-sequence in the Paris Palestine Pavilion exhibition is the Tel Aviv pictures that show the before-and-after images of the city. One can find similar constructs of this image-sequence in Zionism’s discourses, historical and contemporary. For example, in her memoirs, Golda Meir, describing her first encounter with Tel Aviv, constructs a juxtaposition between the modern city and the “barren land.” She writes: “Just outside the station, I caught sight of a tree. It wasn’t a very large tree, by American standards, but it was the first one I had seen that day, and I thought that it was like a symbol of the young town itself, growing miraculously out of the sand.”26 The myth of making the desert bloom, Meir’s tree that grew miraculously in the sand, and—more recently—the only democracy in the Middle East, are just different forms of mobilizing image-sequence to say that the settler colony is an oasis of civilization in the midst of savagery.

Image-sequence as a media technology has a long history of being mobilized in colonial world fairs and exhibitions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Its mobilization of inter-iconicity among multiple images to highlight contrast, movement, transformation, and linear temporal progression renders it an effective strategy for portraying ideas of racial evolution and colonial civilizational claims.27 Furthermore, image-sequence is part and parcel of how colonial world fairs became crucial sites for shaping imperial imaginaries.28 Exhibiting one “primitive” culture after another in the metropole, colonial world fairs themselves turned into an image-sequence—an indexical sign of colonial superiority.

Such images constructed in and through world exhibitions also lived beyond them. Exploring the world exhibitions of the late nineteenth century, Timothy Mitchell argues in his essay “The World as Exhibition” that orientalists traveling to the “East” were seeking the “authentic orient” they knew and experienced in the metropole through exhibitions. They “tried to grasp the Orient as though it were an exhibition of itself.”29

Attending these fairs, al-Issa recognized the domain of exhibition-making as a semiotic battlefield of social imaginaries in which publics are cultivated and subjectivities are shaped. He noticed how the Zionist movement and the British Mandate mobilized the format of exhibitions internationally and locally to develop Lockean arguments for the colonial moral and political right to the land of Palestine and he sought to counter this effort through organizing the Arab Exhibitions—an indexical sign of the Arab Nahda.

By showcasing the commercial and industrial innovations of the various Arab countries, the Arab Exhibitions sought to hollow out the colonial claim of superiority, to replace it with an image of a modern Arab nation with rightful claims to independence. However, Resurgent Nahda is careful not to reduce the Jerusalem exhibitions into anti-colonial events or reactions to the colonial exhibitions.30 Framing them negatively and simply as exhibitions organized against the British Mandate and Zionist movement not only centers colonialism but also champions a mode of historiography in which the colonizer always acts and the colonized only reacts.31 Instead, by accentuating the regional Arab dimension in the Jerusalem exhibitions’ titles, inspiration, ideology, and participants, Resurgent Nahda centers the agency of Palestinians as political subjects promoting and implementing their vision for a borderless and prosperous Arab world to which Palestine is geographically and epistemologically central. This imagined Arab geography, and this Arab world to be, is best captured in Jamal Badran’s illustration for the postage stamp of the 1934 exhibition.

These exhibitions circulated the rhetoric of Arab unity instead of colonial fragmentation and served to strengthen economic and cultural ties among Arab nations concretely. They both projected and materialized the image of Arab unity, central to the Nahda. They sketched and prototyped what Sherene Seikaly calls “an Arab Utopia built on the foundations of private property, investment, self-responsibility, and the accumulation of capital.”32 Or, as Abusaada puts it: “The exhibitions turned the hotel into a microcosm of an Arab nation marching towards independence.”33 In that sense, the Jerusalem exhibitions were at once an endeavor to represent the Nahda, to negotiate its content, to hail its subjects, and to materialize it. Here, approaching Resurgent Nahda as a meta-exhibition demonstrates how exhibitions do not simply represent an image. Rather, they call it into being. Exhibition-making is not merely about depicting the world; it is a world-making practice.

I thank Dr. Nadi Abusaada, Dr. Rana Barakat, and the editors of the Avery Review for sharing their critical feedback on the ideas put forward in this essay.

-

In November 2024, Kaph Books published a book with the same title edited by Nadi Abusaada. In addition to an introductory essay by Abusaada and extensive primary material, the book contains important contributions by Kirsten Scheid, Nisa Ari, Sary Zananiri, Nadine Nour el Din, and Wesam Asali, in addition to an interview conducted by Abusaada with artist Samira Badran about the artistic practice of her father, Jamal Badran. While I refer to the book in multiple places here, the scope of this text is limited only to the exhibition. The book, I believe, deserves its own dedicated review to do it justice. See Resurgent Nahda: The Arab Exhibitions in Mandate Jerusalem, ed. Nadi Abusaada (Beirut: Kaph Books, 2024). ↩

-

For more on Al-Ma’rad, see Maissoun Sharkawi, “Exhibiting an Exhibition,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 92 (Winter 2022): 154–159. ↩

-

For more on the exhibition, see Murtaza Vali and Lucas Morin, eds., Guest Relations: 4 November 2023–28 April 2024 (Dubai: Jameel Arts Centre, 2023), link. ↩

-

Today, the Palace Hotel itself is a negative object. As Abusaada notes, in 2008, “under the guise of ‘renovation,’ the hotel was gutted, leaving only its external limestone façade intact.” Nadi Abusaada, “Microcosm of a Nation (2023),” Nadi Abusaada, link. ↩

-

Here, I understand Walter Benjamin’s use of the term “work of art” as per Alfred Gell. See Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998); and Gell, “Vogel’s Net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps,” Journal of Material Culture 1, no. 1 (March 1996): 15–38, link. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin, “Eduard Fuchs: Collector and Historian,” in The Essential Frankfurt School Reader, ed. Andrew Arato and Eike Gebhardt (New York: Urizen Books, 1978), 226–227. ↩

-

Resurgent Nahda also included works by Sophie Halaby, who was supposed to participate in the exhibitions but could not send her paintings in time. ↩

-

While working on this text, a group effort has led to the discovery of a few artworks by Aram Haschadour. ↩

-

Kamal Boullata, “’Asim Abu Shaqra: The Artist’s Eye and the Cactus Tree,” Journal of Palestine Studies 30, no. 4 (July 2001): 68–82, link; Tina Sherwell Al-Malhi, Forgotten Scene: Pioneer Artists from Palestine, vol. 1: Six Pioneer Artists from Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Al-Wasiti Art Center, 2003); Rana Anani, “Art History Without Art [Arabic],” Journal of Palestine Studies, no. 129 (Winter 2022): 165–184. ↩

-

In the November 2024 issue of the Avery Review, Abusaada wrote an interesting text that examines how loss shapes the history of Palestine’s art. See Nadi Abusaada, “The Many Worlds of Palestinian Art: Disrupted Journeys and Awakened Pasts,” Avery Review, no. 69 (November 2024), link. ↩

-

This argument has two faces. The first emerges out of a Zionist discourse that denies and erases Palestinian creative practices as part of its broader settler colonial logic of elimination that targets everything Palestinian. For example, American artist Elias Newman, who organized the art section of the Jewish Palestine Pavilion in the 1939 New York World’s Fair, published a catalog on that occasion titled Art in Palestine. The pavilion, the catalog, and the reviews celebrate the development of “Palestinian Art” or “Palestine Art,” but include no mention or reference to any artists or artistic practice in Palestine other than that by Zionist settlers. See Elias Newman, Art in Palestine (New York: Siebel, 1939). The second face of this argument ties directly to the Nakba’s rupture and its epistemological ramifications. It results from the faulty conclusion that takes the lack of evidence as evidence of a lack. See, for example, Wijdan Ali, “Modern Arab Art: An Overview,” in Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World, ed. Salwa Mikdadi (Washington, DC: International Council for Women in the Arts and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1994), 72–118; Samia Taktak Zaru, “Palestine,” in The Emergence of Arab Plastic Art, ed. Wijdan Ali (Amman: Royal Society of Fine Arts, 2021). ↩

-

For more on the question of writing history and archival absence, see Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14. ↩

-

For more on this collection, see Gish Amit, “Salvage or Plunder? Israel’s ‘Collection’ of Private Palestinian Libraries in West Jerusalem,” Journal of Palestine Studies 40, no. 4 (2011): 6–23, link. ↩

-

The New Historians are a group of Israeli historians who in the 1980s questioned the official Zionist discourse on the 1948 Nakba, relying mainly on recently declassified Israeli archives. ↩

-

Hashem Abushama, “‘According to Whose Archives?’: The Tantura Massacre and Revisionist Israeli Historiography,” Institute for Palestine Studies (blog), January 30, 2022, link. ↩

-

This painting is itself an interesting example of a truthful imagined composition that challenges the presumed factuality of the photograph. Saig, who copied this image from a photograph taken by the American Colony Photography Department, took the liberty of making a few changes to the composition that in effect decentered the British soldiers, making Hussein al-Husayni, the mayor of Jerusalem, the focus of the image. Kamal Boullata, Palestinian Art: 1850–2005 (London: Saqi, 2009), 117–119; Nisa Ari, “Spiritual Capital and the Copy: Painting, Photography, and the Production of the Image in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine,” Arab Studies Journal 25, no. 2 (2017): 60–99. ↩

-

Stephen Sheehi, Foundations of Modern Arab Identity (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004). ↩

-

Sherene Seikaly argues that the centrality of economy in modern Palestinian thought, especially among those whom she calls the Men of Capital, who approached economy as a means of social reform, shows how the Nahda in Palestine was also an economic project. This challenges the understanding of the Nahda only as a cultural and literary project. For more on the economic manifestations of the Nahda in Palestine, see Sherene Seikaly, Men of Capital: Scarcity and Economy in Mandate Palestine (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016). ↩

-

For more on the role of architects and engineers in the Nahda, see Nadi Abusaada, “The Profession’s Vanguards: Arab Architects and Regional Architectural Exchange, 1900–50,” Architectural Theory Review 27, no. 2 (May 4, 2023): 188–204, link. ↩

-

Issa al-Issa, “Min dhikrayat al-madi (“Memories of the Past”) (1–76), Issa al-Issa Collection, Institute for Palestine Studies Archive, 61. Cited in Abusaada, Resurgent Nahda: Arab Exhibitions in Mandate Jerusalem, 11. ↩

-

For more on how exhibitions feed into national imagination, see Kirsten Scheid, “From the Arab Exhibition to National Art Exhibitions,” in Abusaada, Resurgent Nahda, 16–25; and Kirsten L. Scheid, Fantasmic Objects: Art and Sociality from Lebanon, 1920–1950 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2022). ↩

-

The article does not credit al-Issa as the author. ↩

-

Also known as the Bilal Bin Rabah mosque, it is a shrine located in Bethlehem believed to be the burial site of Jacob’s wife Rachel. The site, which holds religious significance to Jews, Christians, and Muslims, lies today behind the Apartheid Wall, effectively denying Palestinians access to it. ↩

-

Arthur Balfour was a conservative British politician. In 1917, as the foreign secretary, he issued the Balfour Declaration supporting the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. ↩

-

Issa al-Issa, “The Palestine Pavilion in the Paris Exposition and the Levant Fair in Tel Aviv,” Filastin, March 6, 1932. ↩

-

Golda Meir, My Life: The Autobiography of Golda Meir (London: Futura Publications, 1977), 58. ↩

-

Angela Reyes, “Image into Sequence,” Semiotic Review 9 (2021), link. ↩

-

These exhibitions occupied a space between entertainment, economic development, and imperial knowledge production, and played a significant role in the formation and nourishment of imperial imaginaries around notions of “primitive” peoples, the exotic Orient or East, and the civilized European colonialist. See Timothy Mitchell, “The World as Exhibition,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 31, no. 2 (1989): 217–236; Burton Benedict, “International Exhibitions and National Identity,” Anthropology Today 7, no. 3 (1991): 5–9, link; and Adam Kuper, The Museum of Other People: From Colonial Acquisitions to Cosmopolitan Exhibitions (New York: Pantheon Books, 2024). ↩

-

Timothy Mitchell, “The World as Exhibition,” 233. ↩

-

Refusing to read the Arab Exhibitions as essentially and merely Palestinian reactions to British and Zionist colonialism could perhaps be seen as part of a broader critique of historical accounts that reduce the Nahda to a movement driven purely by a reaction to European modernity and in reference to it, aiming, at best, to reproduce a localized version of European modern thought. ↩

-

Rana Barakat, “Writing/Righting Palestine Studies: Settler Colonialism, Indigenous Sovereignty and Resisting the Ghost(s) of History,” Settler Colonial Studies 8, no. 3 (2018): 349–363, link. ↩

-

Seikaly, Men of Capital, 17. ↩

-

Abusaada, Resurgent Nahda, 13. ↩

Faris Shomali is a researcher and doctoral candidate in anthropology at the University of Toronto. His doctoral research examines the politics of circulation of Palestine’s art. He co-curated Made Present: Biographies of Artworks Defying the Ongoing Nakba (Alserkal Arts Foundation, 2024). He previously worked as the digitisation manager at the Palestinian Museum Digital Archive and as an assistant researcher at the Muwatin Institute for Democracy and Human Rights at Birzeit University.