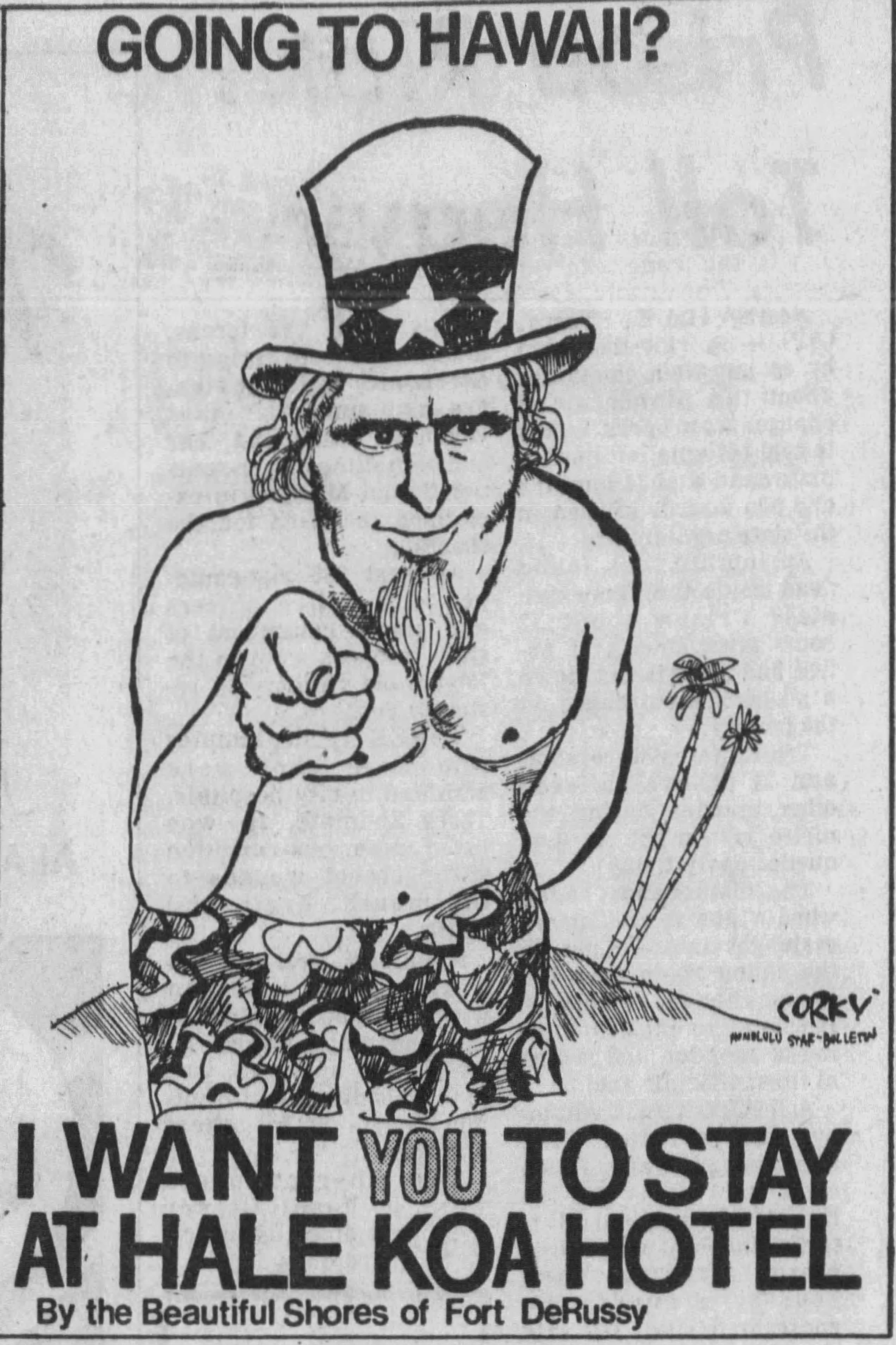

Clad in patterned board shorts and a top hat decorated with stars, Uncle Sam hunches over with one hand behind his back and the other outstretched with a finger pointing out from the pages of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. A small hill dotted with two palm trees occupies the background of the image alongside a question splashed across the top of the page: “Going to Hawaii?” While this editorial cartoon, published in 1975, appealed to Americans looking to fulfill their Pacific Island vacation fantasies, the small text at the bottom of the poster reveals that Uncle Sam was speaking to a more specific audience: “I Want You To Stay At Hale Koa Hotel… By the Beautiful Shores of Fort DeRussy.”1 The cartoonist’s recall of Fort DeRussy, a defunct US military base turned recreation center on the south shore of O‘ahu, is a direct appeal to US armed forces personnel.

Built in 1975, the Hale Koa Hotel—the so-called House of the Warrior—is owned and operated by the US Department of Defense (DoD). Located on 72 acres in Waikīkī at Fort DeRussy, it offers a home away from home for military servicepeople and their families.2 The hotel’s distinctive history among older, iconic Waikīkī hotels, such as the Royal Hawaiian (built in 1927), disrupts popular narratives that position the Hawaiian Islands as a multicultural paradise. The Hale Koa served (and continues to serve) as a concrete backdrop for military families to partake in a “Hawaiian” experience, belying the fact that acquiring the land through Indigenous dispossession and then restricting access to the property deepens the divide with Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) who seek familial retreat in their ancestral homeland.

In January 2020, the Hale Koa Hotel underwent an interior and exterior renovation, which attempted to address critiques that have mired the hotel for decades, namely that it fell short of providing its guests a self-contained resort experience. However, three months after the unveiling of the renovation, and in the midst of COVID-19, a banner appeared on the Hale Koa’s website announcing its temporary closure “to ensure the health and well-being of service members and their families.” The consequences of the hotel’s closure in response to the pandemic not only affects the local economy and military families but also brings the health disparities between Kānaka Maoli and non-Native residents to the fore. According to public health scholar Keawe‘aimoku Kaholokula, the virus has disproportionately affected Kānaka Maoli given their work in the high-risk, high-exposure service industry and their likelihood of residing in multigenerational households.3 Despite the risks, the Hale Koa reopened for guests on official military orders in August—the same time that the Pentagon refused to release coronavirus statistics for US military stationed in Hawai‘i. The Hale Koa Hotel signifies a form of imperial hospitality that upholds economic saliency for Pacific Islander communities while it also disentangles itself from the health and wellness of these same communities, a dynamic that extends historical colonial practices and violences that are very much part of the status quo today.

Aggressive Acquisition

Over the course of many centuries, Hawaiian society developed complex political and social systems rooted in the landscape—systems that would become upended in service of post-contact, foreign-dominated approaches to private landownership and development. The ‘āina (“land,” or “that which feeds”) was collective and administered under the general auspices of the ali‘i (“island ruler”) and mō‘ī (“monarch,” the highest-ranking ali‘i in all the islands). Hawaiians resided in self-sustaining land units encompassing broad plains near the sea and running up valley ridges to the mountains. These wedge-shaped divisions, or ahupua‘a, allowed for the equal distribution of resources necessary to sustain life. Food, shelter, clothing, tools, transportation, and medicine derived from the ahupua‘a system supported an estimated four hundred thousand to eight hundred thousand Hawaiians. As one such ahupua‘a, Waikīkī’s thin ribbon of sand—surrounded by wetlands, mudflats, duckponds, and fishponds—was a source of nourishment for Kānaka Maoli, offering abundant fish and the space to support the cultivation of taro.4

Western systems of landownership began to infiltrate Hawai‘i through a series of laws supported by American merchants and missionaries who settled in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i. The Māhele of 1848 and the Kuleana Act of 1850 established forms of governmentality that drastically altered pre-contact Hawaiian ontologies. Spiritual, ancestral, and sustainable engagement with the land by Native communities meant little within capitalist systems of trade and profit. Whereas land was communal under the tenure system of Kānaka Maoli, these new laws prescribed private landownership and were the result of the selective appropriation of Western ideologies adopted by Kamehameha III (who reigned between 1825 and 1854), the Hawaiian mō‘ī.5 Government strategies in support of private property positioned Hawai‘i within the modern state of nations, a strategy embraced by the Hawaiian elite to combat colonial encroachment by US-backed interests.6 Pointing to the inherent paradox between maintaining Hawaiian independence and ascribing to Western colonial logics, particularly regarding the commodification of land, J. Kēhaulani Kauanui writes that the approach taken by the mō‘ī to link landownership to Western conceptions of “civilization” sought to “put Hawaiians on the same playing field as the otherwise would-be colonizer… holding fee-simple titles [to land] became a way to transcend supposed savagery.”7

Hawaiian leaders employed and worked alongside Western settlers to transform communal land to private property. The mō‘ī culled governmental expertise from foreign settlers, enacting laws and establishing institutions with the intent to preserve Hawaiian sovereignty; these same settlers organized and operated the new systems, effectually rendering Hawaiians unable to govern their own affairs.8 Whereas land rights benefited the settler elite, the majority of individuals were subject to what Brenna Bhandar terms a “racial regime of ownership.” Bhandar’s account of property as a commodity entrenched within laws inextricably tied to the production of racial subjects aligns with Cheryl I. Harris’s assertion of whiteness as property, claiming that whiteness has value encoded within property laws and social relations. Turning to the scholarship of Frantz Fanon, Cedric J. Robinson, and Cornel West, Bhandar extends that Western property laws relied upon racial concepts of the human where Blacks were rendered non-human property and Indigenous communities savage.9 The supposed “violent propensity” of Hawaiians paired with a hierarchical, genealogical governing structure recognizable by non-Hawaiians paved the way for Western economic and political systems to alter the composition of land tenure in Hawai‘i and, ultimately, made large swaths of the island available for private US military use in the form of military bases, training facilities, hospitals, and recreation accommodations.10

Adept Negotiation

The largest transformation of Waikīkī’s shoreline began in the aftermath of 1896, when the US federal government and its military took advantage of laws passed in the Republic of Hawai‘i legislature requiring landowners to rehabilitate “unsanitary” wetlands, lest they lose the land.11 Through legal maneuvering the US Army aggressively acquired 70 acres of “unsanitary” land at Waikīkī to build Fort DeRussy in 1908 in accordance with US military needs.12 In 1911, Batteries Randolph and Dudley were constructed of reinforced 12-inch concrete walls and bolstered by artillery equipment to provide defense for the island. The US Army Corps of Engineers undertook a sequence of coastal engineering projects to widen the beach for military exercises and, later, for military recreation. They dredged sand, coral rubble, and reef rock to extend the beachfront, building a seawall to protect the shore from waves and tides.13 Notably, Fort DeRussy never experienced combat operations and went out of active service after World War I. Military decision-makers reconstituted the physical conditions of the fort into a public beach park in a highly urbanized environment, a move that permanently associated Hawai‘i with the pleasure-oriented consumption of the military-industrial complex.

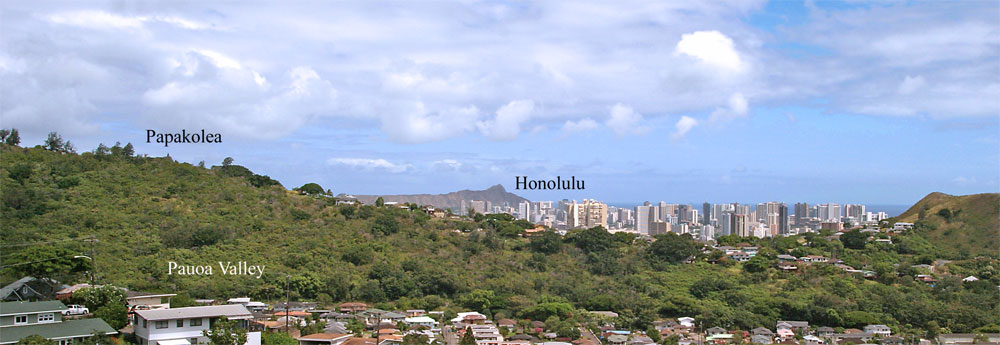

With the acquisition and then construction of Fort DeRussy, many Kanaka Maoli families relocated to Papakōlea (the resting place of the plover) on the slopes of Punchbowl between Pauoa Valley and Makiki Heights. Papakōlea’s residents were forced to reside in makeshift dwellings composed of packing boxes and lumber scrapes, rendering it a “squatter” community to elite settlers.14 The designations “squatter” and “squatter settlement” served to establish residents without legal claims to their land as transitory, unreliable, and poor—and, especially in the case of Papakōlea, neglected the fact that Hawaiians have historical continuity with pre-colonial island society.15 (Mis)labeling Hawaiians as “squatters” and Papakōlea as a “squatter settlement” concealed the legislative acts and economic disparities that displaced Kānaka Maoli from their ancestral ahupua‘a to make way for large-scale hotel development along Waikīkī’s shores.

Western notions of (un)civilized polities and societies underscored the erroneous belief that Hawaiians needed government oversight to address the new informal housing culture that emerged at Papakōlea and other island communities. In partnership with Prince Kūhiō—a non-voting delegate from Hawai‘i to the US House of Representatives—the US federal government established the Hawaiian Homes Commissions Act (HHCA) of 1921.16 The stated objective of the act included “the rehabilitation of native Hawaiians [and] native Hawaiian families” by developing and delivering land to individuals with “at least one-half part” Hawaiian blood.17 As such, homesteads were established throughout the entire Hawaiian Island chain.18 Each homestead consisted of a small parcel of land, leased to residents for $1 per year for 99 years, that could be used for land cultivation or to build a house. Through the HHCA, the US government appropriated Hawaiian lands and gave them a legal context through homesteading. As a continuation of nineteenth-century laws that claimed authority and title over Hawai‘i’s lands, the HHCA preserved economically valuable lands for government institutions, privately owned companies, and monied individuals—a move that compelled Hawaiians to participate in capitalist systems to ensure the economic and physical well-being of their communities.

When Papakōlea became an officially sanctioned homestead in 1934—with paved streets, sidewalks, streetlights, and a sewage system—residents ceased being “squatters” and became “tenants at will.”19 Detached homes intended to accommodate the nuclear family projected a middle-class lifestyle consistent with modern ideas of housing. Architectural respectability, in the form of “attractive little houses in flower filled gardens,” stood in accordance with built traditions from the US continent and made the urban Hawaiian homestead palatable to white audiences.20 Government officials lauded homestead residents as productive citizens of the nation. Local newspapers publicized the ways in which Hawaiians cultivated the neighborhood’s “rocky terrain” into craft yards with hibiscus flowers and vegetable gardens, a congenial narrative that markedly omitted and continues to omit the forced removal of Hawaiians from the wet nourishing lands of Waikīkī.21 These stories were ripe with descriptions of homestead architecture and manicured landscapes as “neat” and “clean,” terms long coded as anti-Black and anti-Indigenous.

Nevertheless, for Hawaiians, simply living on the land was an act of resistance against the settler state and its racialized media claims. The land remained central to Hawaiian identity, and as John K. Wright, Jr. proclaimed: “… it would take the guns of Fort Shafter to blast us from Papakōlea, where the navels of generations of our sons are buried in the soil.”22 Despite adopting Western residential plans on the urban homestead, Papakōlea residents continued to adhere to social practices regarding their ‘ohana (family)—a word deeply associated with Hawai‘i’s topography. As explained by Valli Kalei Kanuha,

The literal translation of the Hawaiian word for family,‘ohana, has its origins in the taro plant… taro (kalo) is one of the few edible sources from which the emerging shoots, or ‘oha, sprout from the mature corm, or makua, which is also the Hawaiian word for “parent.” When joined with nā to form the plural “many,” nā ‘ohana attests to the symbolic meaning of the family as a collective that gives life, nourishment, and support for the growth and prosperity of blood relatives as well as extended family, those joined in marriage, adopted children or adults, and ancestors living and deceased.23

Given the ‘ohana framework, the small footprint of the homestead house did not (and does not) adequately accommodate Hawaiian families. Continuous calls for larger plots of land and for the expansion of homesteads to “undevelopable” land seek to incorporate the manifold Kanaka understanding of ‘ohana within US government policy.24

As O‘ahu’s only urban homestead, Papakōlea’s location gave its residents easy access to work in Waikīkī’s militourism economy, defined by Teresia Teaiwa as the “intersection of tours of duty with tours of leisure.”25 The American imperialist economy was/is predicated on projecting paradisiacal visions of Hawai‘i. As Christine Skwiot and Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez remind us, paradise is not a fixed image. Paradise needs to be perceived as “passive” and “penetrable” so that it can be dominated. Paradise requires labor.26 Therefore, the militarized settler state and its tourist economy forced Hawaiians to participate in its development as service work became necessary for the survival of the community within an extractive pecuniary system.27 Still, Hawaiians subversively acknowledged their intrinsic and ancestral link to a landscape that facilitated these capitalist systems of exchange. Metaphors making the connection between land and water reverberated throughout the community, as residents pointed to the rich legacy of artists who “poured down” from Papakōlea to work at hotels on the shores of Waikīkī.28

Ambassador of Aloha

During World War II, Waikīkī became a “playground” for the military. There, military personnel reveled in the sun and surf at Waikīkī Beach. The US Navy exclusively leased the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, the most famed hotel on Waikīkī’s shores near Fort DeRussy and the site where Queen Ka‘ahumanu’s Summer Palace once stood, from Matson, Inc., a US transportation company founded in 1882.29 Officers rented rooms for $1 per night and enlisted men slept for free at the pink stuccoed, Spanish Baroque, Mission-styled hotel.30 During the war, the Royal Hawaiian Hotel adopted a desegregation policy, which meant sailors of all races shared rooms despite the fact that the US armed forces relegated Blacks to segregated units, training schools, and camp facilities.31 The racial subjectivities of Black soldiers and sailors on Native land in a settler state called out the contingencies of racial regimes of ownership. It revealed the ways in which the varied meanings of property and access shift over time and space, depending on the forms and temporalities of possession, whether permanent ownership or temporary leasing. The notion of property, then, begins to look fuzzy in the context of settler colonialism as a continuously shifting structure that requires malleability in the legal procedures and social mechanisms it entreats to retain control of Indigenous lands.32

The racial regime of ownership that allowed the US military to acquire land for Fort DeRussy in 1908 and for the military to occupy the landscape for leisure during World War II legitimated the construction of the Hale Koa Hotel. Although Hawai‘i’s tourism industry was in decline during the Vietnam War, the government wanted a residence to provide rest and recuperation for its soldiers at Fort DeRussy.33 According to Fred White from the Honolulu-based architectural firm Lemmon, Freeth, Haines, Jones and Farrell, which was commissioned to build Hale Koa, the hotel needed to reflect the “grace and beauty” of the Hawaiian Islands. It was to be, in the words of The Honolulu Star-Bulletin, a “distinctly unmilitary” military hotel.34 The architects designed a fifteen-story building known as Ilima Tower in the International Style with 416 rooms, a post exchange, and various shops. All rooms—from studios to deluxe suites—were available to any military guest regardless of race or ethnicity, with prices determined by rank and room category. The view from each room’s lanai toward Waikīkī Beach and out onto the Pacific created a sense of openness that aligned with the architectural firm’s philosophy that every building should fit into the environment and reflect the prevalence of indoor/outdoor living in Hawai‘i.35 The demolition of military structures along the Waikīkī shoreline during the construction of the Hale Koa portended the literal openness of the property that stretched from the hotel to the sea.36

That access at Hale Koa is restricted to those with a valid military identification card calls into question the hotel’s openness and its claim to be an “ambassador of aloha,” a position derived from a US social system that calls on its multicultural citizenry to be “kind, loving, open, and nonconfrontational.”37 Settler appropriation of aloha as a universalizing Pacific principle sustains American hegemony by insinuating that Hawaiians are complicit in its foreign adoption. Stephanie Nohelani Teves contextualizes aloha by framing it within ideological discourses emanating from state institutions and actors. In her estimation, US systems of power led to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the subsequent establishment of the State of Hawai‘i in 1959. These same systems, including the US military, participate in crafting and maintaining the tourist industry that perpetuates the notion that Hawaiians are adept at “performing culture and physical labor.”38 Teves makes the link between aloha, the state, and tourism in her discussion of Hawai‘i’s designation as the “Aloha State”:

the intertwining of aloha with the state created the ruse that the state represented the interests of aloha and coded aloha as the epitome of what is “Hawaiian” to an increasingly globalized media… The naming of the state in this manner solidified institutional support of aloha, and the statist imperative to perform aloha implored citizens or subjects to perform aloha as a requirement of civic participation and to function within a capitalist system.39

Instead of aloha as a ritualized performance signifying Hawaiian cultural mores, it came to embody a “so-called kindness” that extended beyond Hawaiians to include the ethnically diverse, multicultural, and military populations of Hawai‘i.40

The convergence of capitalism, tourism, and the military at Waikīkī relies on aloha and other rhetorics of a perceived Hawaiianness to foster a sense of belonging among the military at the Hale Koa. Both the DoD and the architects of the Hale Koa capitalized on the hotel’s Hawaiian setting beginning with the name itself. Hale Koa, House of the Warrior, has dual associations. Hale are places for rest constructed of wooden rafters and ridge poles latched together by pili grass, pandanus leaves, and ti leaves; Koa signals the legacy of elite Kanaka fighters who served at the pleasure of ali‘i and who fashioned their weapons from the koa tree.41 This rhetorical device aligned Hawaiian history with a welcome military narrative. Accordingly, the blank façade of the Ilima Tower, as a US military defense-backed site of leisure, communicated a non-offensive placelessness indicative of the International Style of the mid-twentieth century—a design choice intended to provide guests with comfort and order by tapping into a familiar architectural style made prominent in major cities on the US mainland and in accordance with US military base architecture around the world.42 The Hale Koa’s neutral façade allowed Hawai‘i’s culture and environment to take center stage, suggesting the appearance of an imperial hospitality supported by Natives. The ocean, lūaus (complete with an imu pit ceremony), live entertainment, and place-specific décor provided a variety of visual cues for military guests that simultaneously linked the Hale Koa to home and to notions of paradise within US empire.

The Hale Koa’s dedication in June 1975, the same month as the Army’s two hundredth birthday, leaned into the narrative of Hawai‘i as an integral part of the American Pacific. Local music talent including Don Ho and Danny Kaleikini, born and raised on the Papakōlea Homestead, provided the entertainment. Senator Daniel K. Inouye gave the keynote address before General Fred C. Weyand, chief of staff of the Army and former commander of the US Army, Pacific, extended official remarks. Weyand designated the hotel as a “living memorial” to all Americans who served their country in Pacific wars.43 The dedication notably evaded the pre-contact history of Waikīkī as a site of Hawaiian nourishment and replaced it with a memorialization of US military valor and victimization.

The pomp and circumstance of the hotel’s dedication carried over to the grand opening on October 25, 1975. The proceedings began with an outdoor conch-shell-blowing ceremony before General Thomas Greer, head of the US Army Support Command in Hawaii, cut the maile lei to officially open the facilities.44 Blowing the pū (conch) is a deep part of Hawaiian culture. Sounded in accordance with Hawaiian protocol, it is a call to the divine announcing the official beginning of a sacred ceremony; conchs are also used to communicate across the water, requesting and granting permission to come to shore. Moreover, the lei has become a symbol of welcome, part of the “genealogy of hospitality” tied to Hawai‘i’s culture of exchange.45 The purposeful use of Hawai‘i’s flora and fauna for entertainment stripped the territory’s topography and culture of its Native specificity and, instead, made them available for consumption, all in the service of empire.46

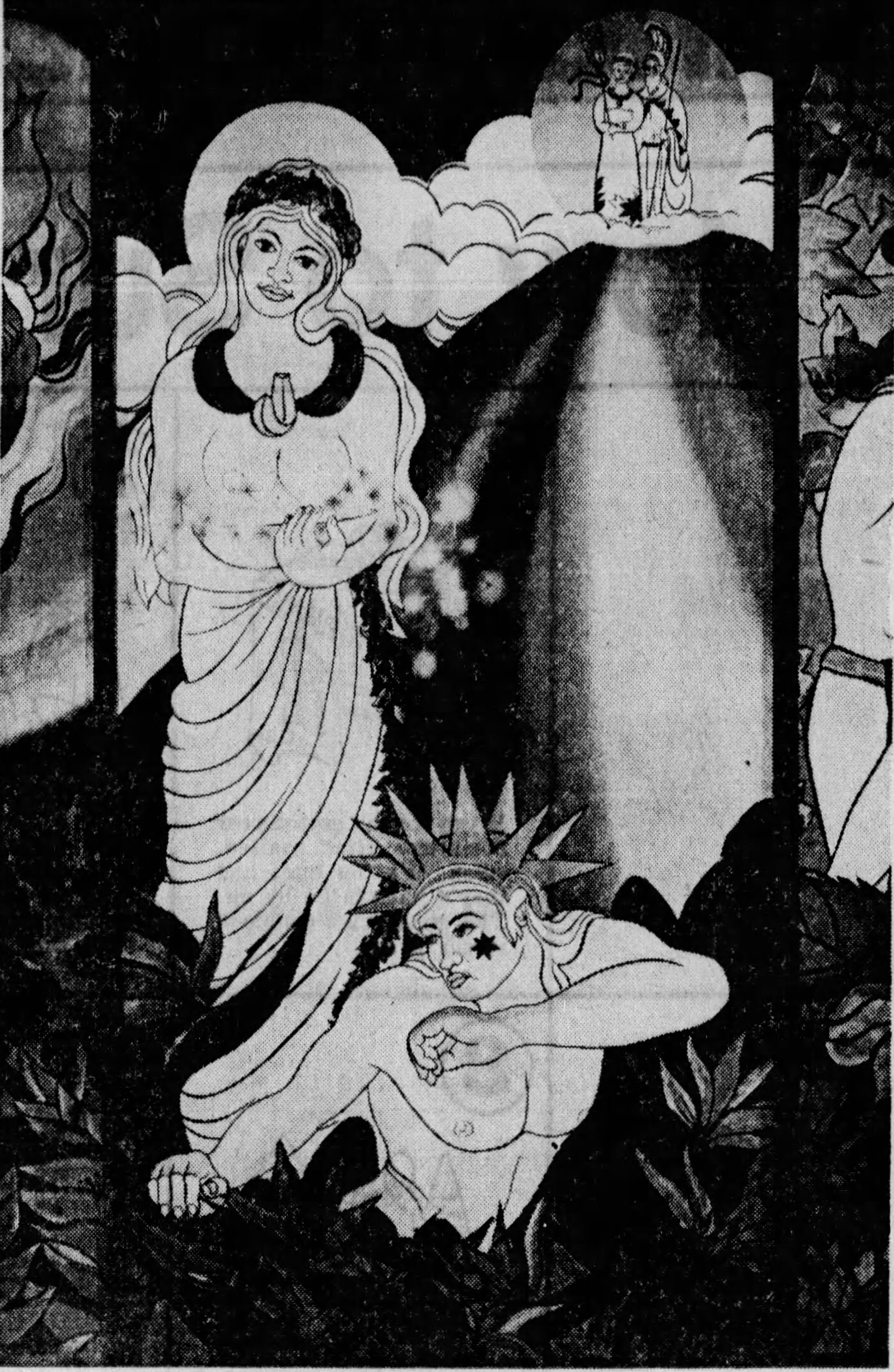

Inside Hale Koa, the Warrior Lounge, Waikiki Ballroom, and Pele’s Cauldron (named after the Hawaiian goddess of fire) provided a gathering space for guests to eat and drink surrounded by murals of Hawaiian gods and goddesses adorning the walls. One large-scale work by Calvin Keawe Nary visually narrated the story of La‘ieikawai, a Hawaiian chiefess whom the gods deified.47 The mo‘olelo (story) is an account of abduction and seduction, heaven and earth, gods and commoners; it is a mo‘olelo intimately rooted to place. The nineteenth-century Hawaiian translator of the mo‘olelo, S. N. Haleole, explains how concepts of place manifest in the narrative: “[place names] are applied in lavish profusion to beach, rock, headland, brook, spring, cave, waterfall, even to an isolated tree… they are affixed to the winds, the rains, and the surf or sea.”48 Like the ties that bind at Papakōlea, Nary’s mural at the Hale Koa asserts a rootedness of Hawaiian identity and cultural survival within the islands’ geography and the “spiritual and kinship bonds between people, nature, and the supernatural world.”49 It contains a veiled subtext for non-Hawaiians about a storied landscape that unites Kānaka Maoli with their kūpuna (“elders, ancestors”) and, as Kapulani Landgraf asserts, “debunks the myth of Hawai‘i as paradise” in favor of asserting responsible care for the ‘āina provided by Kānaka Maoli.50

Palatable Appropriation

Much has changed at the Hale Koa since its 1975 grand opening, and it has since undergone several renovations. In 1995 the hotel expanded with a three-story garage and an additional twelve-story, 396-room tower complete with a pool, new restaurant, lū‘au garden, and fitness center. Nearly two decades later, plans were put in motion to upgrade the hotel and, again, expand its facilities. In 2018, Haskell, a Jacksonville, Florida–based firm, completed the hotel refurbishment project with new furnishings, fixtures, and flooring; in February 2020, Stellar, another Jacksonville firm, completed the $14 million, 8,000-square-foot Ilima Swimming Pool Complex. Describing the most recent project, Stellar writes:

All design elements of the pool complex incorporate Hawaiian culture and aesthetics. The entrance is flanked by waterfalls cascading down lava rock walls with pillars topped by fire bowls, and gas tiki torches line the perimeter. The pool complex also features brick pavers throughout, and the resort’s renowned Indian Banyan tree, Esmerelda, is prominently featured in the design… The local culture drove much of the design, and nearly all of the materials and landscaping were sourced from the island… This isn’t your typical resort pool, either: It’s designed in the shape of a traditional Hawaiian war club with the surrounding sunshades resembling the club’s shark teeth. It’s both unique and symbolic.51

Much like the 1975 hotel design, Hale Koa’s latest complex attempts to bridge the architectural placelessness of the building’s façade with a fixed sense of Hawaiian culture and history, and to capture an audience in search of a packaged historical paradise. This DoD property—which heavily relies on Hawaiian aesthetic tropes—reflects the ways in which capitalist systems of exchange work in and through the US government to uphold Hawai‘i’s militourism economy on the shores of Waikīkī.

The Hale Koa Hotel (in both iterations) and Fort DeRussy Beach Park make militarism palatable for American tourists. While civilians are barred from entering the hotel, they are welcome to enjoy the grounds, grills, picnic tables, volleyball nets, and paved sidewalks at the adjacent park. Waikīkī’s militarized shoreline “usurps the curative powers of Waikīkī” as a storied place imbued with memories and possible futures for Kānaka Maoli.52 The traumas of violence and dispossession wrought on Hawaiian land by the US military, as well as the contemporary health disparities and economic strains experienced by Kānaka Maoli during the COVID-19 pandemic, are shrouded in the glorification of a benevolent United States, a nation where, as Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez maintains, “administrative control, ideological frameworks, and territorial occupations” uphold American hegemony in the Pacific.53 The Hale Koa and Fort DeRussy Beach Park continue to normalize military presence in the islands and, effectively, stall discussion about the demilitarization of Hawai‘i made by Kānaka Maoli, activists, artists, and scholars, to name but a few.

To be sure, Hawaiian processes of reclamation move beyond the constrained logics of US power that focus on Hawaiian scenes of dispossession. Kānaka Maoli actively partake in kinship practices on single-family and multigenerational homesteads that restore the livelihood and identity of the community—an identity that cannot be captured and is distinct from the contrived notions of aloha and Hawaiianness absorbed by military families temporarily housed at the Hale Koa on Waikiki’s hallowed shore. Papakōlea reflects Hawaiians’ strategic ability to adeptly negotiate a legal system defined by Western concepts of private property ownership. The homestead provides an arena where Hawaiians can, at least partially, liberate themselves from the state by simply remaining on land that aligns them with their cultural practices.54 The ‘āina, or that which feeds Hawaiians, is both “a literal and spiritual descriptor… of sustenance, growing knowledge, and inspiration.”55 Over the years, homestead associations, neighborhood groups, and community-led planning boards charged with fostering economic development, culture, and education have been brought to fruition by resident participation, social activist leadership, and guidance from kūpuna. This type of work aligns with decades-long social movements that affirm Hawaiian ways of life in perpetuity. With goals to promote Hawaiian self-determination by developing strong and effective community leaders, these alliances signal an active movement by Kānaka Maoli to protect Hawai‘i’s land, history, and spiritual practices.

-

Corky, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 12, 1975, 16. ↩

-

In accordance with Hawaiian orthography, I use diacritical marks for Hawaiian words and names. I also do not italicize Hawaiian terms (unless they are italicized in a primary or secondary source) in order to refute a monolinguistic culture of othering. ↩

-

Ku’uwehi Hiraishi, “Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders Face Higher Rates of COVID-19,” Honolulu, HI: Hawai’i Public Radio, April 27, 2020. ↩

-

Andrea Feeser and Gaye Chan, Waikīkī: A History of Forgetting and Remembering (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006), 39–53. ↩

-

J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, Paradoxes of Hawaiian Sovereignty: Land, Sex, and the Colonial Politics of State Nationalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 93. ↩

-

Kauanui, Paradoxes of Hawaiian Sovereignty, 97. ↩

-

Kauanui, Paradoxes of Hawaiian Sovereignty, 97. ↩

-

Sally Engle Merry, Colonizing Hawai’i: The Cultural Power of Law (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 89. See also Kauanui, Paradoxes of Hawaiian Sovereignty, 15. ↩

-

Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 5–7. ↩

-

Rona Tamiko Halualani, In the Name of Hawaiians: Native Identities and Cultural Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 26–27. The murder of Captain James Cook of the British Royal Navy by Hawaiians at Kealakekua Bay in 1779 and subsequent paintings depicting the violent encounter exacerbated the trope of the “savage” Polynesian, one that linked them to Black “primitive” Melanesians and occasionally bound indigeneity with Blackness. For more, see Maile Arvin, Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019). ↩

-

Sanford Ballard Dole, a Hawai’i-born descendent of US missionaries, led a group of American sugar planters to illegally overthrow Hawai’i’s mō’ī, Queen Lili’uokalani (who reigned between 1891 and 1893). Dole then served as president of a short-lived provincial government and the Republic of Hawaii from 1894 to 1898 until Hawai’i became an official territory of the United States in 1900. ↩

-

Feeser and Chan, Waikīkī, 44. ↩

-

Amid US military construction along Waikīkī’s shore, coastal and sand excavation disrupted over 150 Hawaiian burial sites where iwi kūpuna (ancestral bones) had been buried for centuries. Iwi kūpuna hold the most sacred mana (spiritual, divine, and political power) and are the embodiment of ancestors that continue to guide Kānaka Maoli, physically and spiritually. See Noelani Goodyear-Ka’ōpua, Ikaika Hussey, and Erin Kahunawaika’ala Wright, eds. A Nation Rising: Hawaiian Movements for Life, Land, and Sovereignty (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014). See also “POD Archeologist named as Federal Employee of the Year,” The Pacific Connection 30, no. 2 (May/June 1996): 2–3. ↩

-

Judith Schachter, “From ‘Squatter’ to Homesteader: Being Hawaiian in an American City,” City & Society 28, no. 1 (2016): 23–47. See also Lawrence H. Fuchs, Hawaii Pono: A Social History (Honolulu: Bess Press, 1961), 69. ↩

-

Schachter, “From ‘Squatter’ to Homesteader,” 26. ↩

-

Testimony of Jobie M. K. Masagatani, Chairman Hawaiian Homes Commission, Before the House Finance Committee on the Fiscal Year 2019 Supplemental Budget Request of the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, (January 16, 2018). ↩

-

Charles Hillinger, “Way of the West—Hawaiian Style: Homesteading Gives Islanders Chance,” Los Angeles Times, September 1, 1985. Homesteads are carved from Hawaiian Crown Lands, lands once held in title by the mō’ī prior to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and, thereafter, held in public trust by the Republic (1894–1898), Territory, and State of Hawai’i (1959–present). ↩

-

James Clarke, “Papakolea… Homes on the Hillside,” The Honolulu Advertiser, July 1, 1951, 54. ↩

-

“Papakolea: Little Hawaiian Town,” The Honolulu Advertiser, December 8, 1946, 13. ↩

-

Clarke, “Papakolea… Homes on the Hillside.” ↩

-

“Know Your Own Backyard,” Honolulu Advertiser, August 23, 1954, 6. ↩

-

Valli Kalei Kanuha, “‘Na ‘Ohana: Native Hawaiian Families,” in Ethnicity and Family Therapy, eds. Monica McGoldrick, Nydia Garcia-Preto, and Joseph Giordano (New York: Guilford Press, 2005), 66. ↩

-

Kristen Corey, et al. Housing Needs of Native Hawaiians: A Report from the Assessment of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Housing Needs (Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, 2017), 66. ↩

-

Teresia Teaiwa, “Reflections on Militourism, US Imperialism, and American Studies,” American Quarterly 68, no. 3 (2016): 850. ↩

-

Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawai’i and the Philippines, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 7. See also Christine Skwiot, The Purposes of Paradise: US Tourism and Empire in Cuba and Hawai’i (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011). ↩

-

Ellen-Rae Cachola, “Reading the Landscape of US Settler Colonialism in Southern O’ahu,” feral feminisms 4 (2015): 52. ↩

-

“Know Your Own Backyard.” ↩

-

David Farber and Beth Bailey, “The Fighting Man as Tourist: The Politics of Tourist Culture in Hawaii during World War II,” The Pacific Historical Review 65, no. 4 (1996): 650. Ka’ahumanu (1772–1832) was the favorite queen of Kamehameha I and served as kuhina nui (co-ruler) with Kamehameha II from 1823–1832. Matson, Inc.’s network of luxury liner fleets, shipping containers, terminals, and hotels across Hawai’i are directly associated with the growth of the island’s tourism economy. ↩

-

Don Hibbard, Designing Paradise: The Allure of the Hawaiian Resort (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006), 41–45. See also Kelema Lee Moses, “Kingdom, Territory, State: An Architectural Narrative of Honolulu, Hawai’i (1882–1994)” (PhD diss., Penn State University, 2015), 216–217. ↩

-

Phillip McGuire, “Desegregation of the Armed Forces: Black Leadership, Protest, and World War II,” The Journal of Negro History (1983): 147. Black and white shipmates had different social experiences in Hawai’i. Black sailors lounged in the Royal Hawaiian, frequented “the Black side of town,” and patronized the bars and shops in downtown Honolulu and Chinatown. White sailors frequented downtown Honolulu, but they also left the Royal Hawaiian and leisurely walked the length of Waikīkī Beach toward The Breakers (1942), a Navy beach club on the Diamond Head side of Waikīkī across from Kapiolani Park. ↩

-

Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property, 24. See also Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387–409. ↩

-

The war ended before the Hale Koa’s completion, so its function shifted from an active-duty rest-and-recuperation locale to a retreat from military life for retirees, active-duty military, and their families. ↩

-

“‘Distinctly Unmilitary’ Hotel Set for DeRussy,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 29, 1972, 54. ↩

-

Trina DeNuccio and Mason Architects, “Lemmon, Freeth, Haines & Jones: Mid-Century Context Study (1948–1962)” (2018): 1. ↩

-

“Open DeRussy,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 14, 1975, 54. Old wooden military structures, as well as two Army homes, an officers mess hall, bath house, and post exchange were razed one month prior to the opening of the Hale Koa to make way for a vast open lawn. See “Old Beach Houses to Be Razed,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 13, 1975, 7. Battery Randolph currently serves as the US Army Museum of Hawaii and Battery Dudley is no longer extant. ↩

-

Stephanie Nohelani Teves, “Aloha State Apparatuses,” American Quarterly 67, no. 3 (2015): 707–708. ↩

-

Teves, “Aloha State Apparatuses,” 709. ↩

-

Teves, “Aloha State Apparatuses,” 711. ↩

-

Moses, “Kingdom, Territory, State,” 213–214. ↩

-

Davida Malo, Hawaiian Antiquities: (Moolelo Hawaii) 2. Hawaiian Gazette Co., Ltd., 1898/1903. ↩

-

Fleura Bardhi, “Finding Home in Hotels: Home as Order: An Alternative Perspective to Study Consumption of Servicescapes,” European Advances in Consumer Research 7 (2005): 438. See also Kimberly Dovey, “Home and Homelessness,” in Home Environments, eds. Irwin Altman and Carol M. Werner (New York: Plenum Press, 1985), 35. ↩

-

“Army Chief to Dedicate New Hotel,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 28, 1975, 25. ↩

-

David Tong, “Everyone Rates as VIP at DeRussy Resort Hotel,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 25, 1975, 10. ↩

-

Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez, “Making Aloha: Lei and the Cultural Labor of Hospitality in the Service of Empire,” in Making the Empire Work: Labor and United States Imperialism, eds. Daniel E. Bender and Jana K. Lipman (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 161–182. ↩

-

Sarah Miller-Davenport, “A ‘Montage of Minorities’: Hawai’i Tourism and the Commodification of Racial Tolerance, 1959–1978,” The Historical Journal 60, no. 3 (2017): 817. ↩

-

The mural elicited controversy because of its figural recall of Paul Gauguin paintings and in the whiteness of the central characters. Murry Engle, “Twilight with the Gods,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 30, 1975, 38. ↩

-

S. N. Haleole, The Hawaiian Romance of Laieikawai, no. 4 (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1918), 31. ↩

-

George Hu’eu Kanahele, Ku Kanaka—Stand Tall: A Search for Hawaiian Values (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1986). See also Shawn Malia Kanaÿiaupuni and Nolan Malone, “This Land Is My Land: The Role of Place in Native Hawaiian Identity,” Hūlili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being 3, no. 1 (2006): 283–284. ↩

-

Kapulani Landgraf, “Featured Art: Kapulani Landgraf” (2003), 7. ↩

-

Stellar, “Stellar Completes Renovation of Ilima Pool Complex at Hale Koa Hotel,” news release, January 8, 2020, link. ↩

-

Adria L. Imada, “The Army Learns to Luau: Imperial Hospitality and Military Photography in Hawai’i,” The Contemporary Pacific 2, no. 2 (2008): 351–352. ↩

-

Gonzalez, Securing Paradise, 5, 314. ↩

-

Goodyear-Ka’ōpua, “Introduction,” in A Nation Rising, 12. ↩

-

Manulani Aluli Meyer, “Our Own Liberation: Reflections on Hawaiian Epistemology,” The Contemporary Pacific 13, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 129. ↩

Kelema Lee Moses is an assistant professor of architectural history and urban design at Occidental College. Her work explores the intersection of race, land, and the built environment of the Pacific.