The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion; the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood,

Their colors and their forms, were then to me

An appetite…

—William Wordsworth, “Lines, Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour,” July 13, 17981

Rest is a sign of necrosis. Life is a cycle of jobs. The biosphere is alive

with menthol smoke and my unchecked voicemails. I, for one, used to

believe in God

and comment boards

I wd say how far I am from my mountains, tell you why I carry

Kumeyaay basket designs on my body, or how freakishly routine it is to

hear someone died

—Tommy Pico, Nature Poem, 20172

One day last Fall, my sister and I stumbled on a satirical scene in the Central Park Ramble while on a horticultural tour.3 Our heads were deep in the bushes, inspecting some invasive species or jagged leaf, when we nearly bumped into an old-school cruiser clad like a Techno-Patagonia vision. Standing on an exposed boulder, he was, from the waist up, a collage of meshes and reflective surfaces: a high-tech pullover, polarized glasses, breathable visor, day pack, security clips, carabiners, and zippered pockets. He was naked from the waist down—erection on display—with ventilated hiking shorts around his ankles partly covering heathered wool socks and hiking boots. Our guide, a thoughtful botanist, sputtered as he identified the array of local plants that make up this site of queer history, one of New York’s most storied cruising grounds. We were quickly carried away by the Ramble’s twisting network of paths, a cluck of admonition sounding behind us—or maybe an offer.

In that moment I thought of, and probably considered, a few things (wink emoji). I thought of the flatness of online cruising. I thought of Polari (the queer Esperanto) and communication and signs and signifiers. Mostly I thought of Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem, which I had recently read, and it seemed like a good guidebook to help navigate this encounter: a long-form epic traversing the constructed worlds of longing and absurdity; of nature and artifice.

Cut a section through Central Park and you’ll encounter some real Easter eggs. Under all that nature and all that leisure, you will see traces of gunpowder used to blast out rocky ledge and schist, displaced soil used to smooth out and reshape the landscape, and fragments of residences excised by eminent domain. You’ll uncover remnants of Seneca Village—its fifty-plus homes, three churches, and school—and with it the possibility of a landowning Black middle class, which started to form in 1825 before it was removed just thirty years later. You’ll find unexhumed graveyards of societies that stretch back centuries.4 The park is built on a history (and the literal grounds) of labor and displacement in service of an idealized natural landscape—people and plants cleared out for lawns and carefully prescribed pathways. It’s heralded as the city’s lung; the Ramble as its wilds.

The Ramble itself was not part of Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux’s competition-winning plan for Central Park. It was the labor of its master gardener, Ignaz Anton Pilát, a runner-up in that competition whose proposal so impressed Olmstead and Vaux that they invited him to design key aspects of the park as it developed.5 Pilát had established a career in Vienna and London by reworking parade grounds and other classical gardens into more organic, “natural” landscapes. In other words, by wilding the artificial to bring back some affect of nature. Olmstead and Vaux’s Greensward Plan organized the park around a picturesque series of paths, fields, and dense tree clusters intended to converse with the city beyond. The Ramble was integral to this organization: a moment of delirium and darkness, of getting turned around among tall trees, of dramatic topography and dense underplanting. From broad site planning to detailed planting, Olmstead, Vaux, and Pilát developed strategies to obscure traces of the urban by creating the illusion of the natural, oscillating between open spaces, views, and intimate seclusions; in other words, to balance the technology of the city with a perceived sense of nature’s romance—our Patagonia-clad cruiser the logical outcome as an ideal, though perhaps accidental, citizen. The park’s designers carefully negotiated interactions between nature and artifice, eros and scientific management, that align with a longer history of confrontations between nature and the built environment.

Such illusory acts dog the history of Western landscape architecture and gardening, particularly since the late eighteenth century. Authors of the picturesque and landscape theory from William Gilpin to Thomas Whately to Claude Henri Watelet promoted calibrating and coordinating subject-based experiences of “desire,” “pleasure,” and “survey.” And poetry was vital to these experiences and connections. With Gilpin in hand, William Wordsworth would visit Tintern Abbey (which Gilpin painted) to write his poem “Lines.” At Tintern Abbey he would find color and forms “an appetite”; he would be “well pleased to recognize / In nature and the language of the senses / The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse, / The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul.”6 For Wordsworth, nature acted in service of humanity—a thing to consume, a form of labor, an instrument of pleasure.

Describing architecture’s entanglement with the concept of nature, Adrian Forty writes that “for most of the last five hundred years, ‘nature’ has been the main, if not the principal category for organizing thought about what architecture is or might be.”7 Forty traces the Western European canon to track disciplinary thinking about nature, from Alberti (nature provides a model of harmony for architecture) to Semper (nature is an analogy of architecture) to Ruskin (live in nature; don’t imitate it) to Louis Sullivan (preserve the spirit of nature) to Richard Rogers (architecture should cohabitate with nature). Central Park and its Ramble sit somewhere between—a logical ordering, a designed experience, an interface between built environment and spiritual relief.

Nature is a paradigm that shifts with dominant discourses, from romanticism to humanism to positivism to environmentalism, and that is produced by groups of thinkers bridging poets, writers, scientists, artists, architects, and planners. We have been taught to see nature through Vitruvius and Goethe and Ralph Waldo Emerson and Wilhelm Worringer and Le Corbusier and Adorno and Rachel Carson and countless others. And it’s through this Western perspective that we might understand nature through “appetites” and “desires.” And in wanting to consume it, nature becomes a commodity, property to have or to lose, subject to supply-and-demand chain rules and regulations. If nature is a principal category through which to consider architecture, then what’s our current paradigm? Where do we stand, and why? Before we talk about wilderness or the sublime or blurring inside and out, perhaps even before we think abstractly about perspective or approach or phenomenology, we should ask: how do we define nature, and how do we account for it? Let’s begin with our reading lists. Embracing the ties between poetry, theories of nature, and landscape design: let’s drop the Romantics and pick up another kind of epic. I think every architect and every student of architecture should read Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem.

Aromantic Aesthetics

In Nature Poem, Pico guides us through a surreal mashup of nature and its consequences, from the sparkling and shroudy depths of the ocean to a beer-scented, gravelly voiced sex proposition in a pizza parlor. The long-form, seventy-four-page poem covers a lot of ground, skipping between the vague and the lucid, the big and the small, the human and the artificial in a kind of reverie that speaks to another kind of nature that’s inclusive and cynical and violent and erotic and that is both more and less anthropocentric than our inherited definitions. It feels undeniably spatial—unfolding in episodes and scenes that recall Serlio and Gilpin but undone, reconstituted, and deployed to an entirely different effect.

Consider it an aromantic poem, a rejection of a poetic tradition that venerates the beauty and the tragedy of nature, or that seeks to find some kind of truth in our relationship to it. “I can’t write a nature poem / bc it’s fodder for the noble savage / narrative,” writes (queer, Indigenous) Pico (2). And so, if we think of Pico as another kind of guide, his tour of nature emerges between attenuated interiors—artificial spaces complete with harrowing fluorescent lighting and tiled surfaces—and other kinds of life and other kinds of death. Superficially absent from these scenes, nature instead precedes and exists among them through its constant rejection, evocation, and referencing—hovering over everything like a question or a warning.

Pico first leads us into a pizza parlor, where he is propositioned by a father picking up dinner for his wife and kids. The man “puts his hands on the ribs of my chair asks do I want to go into the bathroom with him / let’s say it doesn’t turn me on at all… This is a kind of nature I would write a poem about” (2). Next, to an exam chair as a dentist fills his mouth with “meaty fingers.” Then to a Karaoke Bar, a singing lesson, a movie theater, a weed dispensary, a White Castle drive-thru. Later, the American Museum of Natural History, a nondescript kitchen table, the subway, the smoking spot behind a school trailer, and onstage. Conflict pervades these spaces, an undercurrent of fear and its inverse beauty not unlike the sublime of the dark woods. Kazuo Sejima told us, in her 2010 Venice Biennale, that “People Meet in Architecture.” There, too, do they ruin each other.

Descriptions of nature fill these interiors. His heart beats like a hummingbird; he lies under the Perigree moon shared worldwide; rains come from “the eyelids of the sky”; hurricanes from minute disturbances (5). Everywhere is marked by structures of oppression—sexual domination, medical procedures, inappropriate questions, habits, and expectations. Such aggressions are naturalized through description—through drying fogs, hunger, valleys and mountains and oceans and celestial bodies. As Pico brings the outside in, so he brings inside out, inflecting nature with our artifice. Looking to the stars, he sees Tracy Anderson in a workout DVD telling him to “reach, like you are being pulled apart” (1). The night sky is reminiscent of a Hollywood movie, water is oil, the breeze is a recovering alcoholic. Nature is “a range of snowcapped mountains on molly and mushrooms and sherbet watercolors” (7). Systems of description and morphology work back and forth, connecting feeling to form, the organic to the unnatural.

“Nature asks aren’t I curious abt the landscapes of exoplanets—which, I thought we all understood planets are metaphors / Like the Vikings, or Delaware” (40). Pico laughs through easy metaphors around nature, bending description into the exaggerated and disfigured like metalepsis on ketamine: Winter isn’t bleak but a “death threat” (5). Animals aren’t encountered in the wild but caged and “literally, fed to the lions” (7). Kumeyaay burial urns aren’t filled with memories but rather emptied and locked in displays at “the Museum of Man” (6). Ruins aren’t picturesque follies but imperialist conquests: “Men smack / the monolights in Mosul back to stone and dust… Thank god for colonialist plundering, right? At least some of these artifacts remain behind glass, says History” (6). Museums recur in Pico’s tour as containers of colonialism’s spoils, where nature, civilization, rite, and ritual are all frozen into a didactic image. Where visitors look on—“it’s horrible how their culture was destroyed,” says one (“as if in some reckless storm”) (56).

Pico’s Kumeyaay upbringing shapes his worldview: “My father… tells me to thank the plant for its sacrifice, son… My mother waves at oak trees” (24). Those rituals backfire as lovers, friends, and strangers forever seek to tie him back to the land. “This white guy asks do I feel more connected to nature / bc I’m NDN… says it’s hot do I have any rain ceremonies” (15). Pico refutes such immediate threads, instead tying together infinitely large and small extremes, from the reaches of space to terrestrial details, as nature’s true form. Everything in between (how we imagine the nature of our everyday) is a form of subjectivity as much as a form of subjugation. Nature has become an articulation of what capitalism and colonization have allowed to persist “outside.” It’s a lawn, a planned wilds, a protected forest. Pico’s response to exploration and discovery— “It’s hard for me to imagine curiosity as anything more than a pretext for colonialism / so nah, Nature I don’t want to know the colonial legacy of the future”—directly refutes the Romantic ideation of the survey promoted by picturesque theorists and romantic poets (40). To see is to discover, is to dominate, is to rework, is to take pleasure. Nature, in these men’s eyes, becomes a subject of power, of domination, and of control.

Nature Poem shifts back and forth in scale, repeatedly drawing us through a sieve designed to recombine us with smaller and smaller parts—ideas and metaphors and feelings and instincts. We now understand that microplastics have attached themselves to the smallest organisms of life, blending “nature” and “artifice” so completely that we cannot understand one without the other. “Science says trauma cd be passed down, molecular scar tissue, DNA cavorting w/war and escape routes and yr dad’s bad dad,” describes Pico (55). We might understand this as a game of evolving standards and effects, echoing Claude Henri Watelet’s prescient and oddly unsettling prediction: “in our society, the more cultivated taste becomes, the more refined artifice must be.”8

Natural Impulses

What about design? Through our tour in Nature Poem, we begin to understand Romantic, Picturesque nature as artificial, prescribed, tamed, and irrelevant—an alibi used to prop up colonialism, slavery, capitalism, and measures of social control. “It seems foolish to discuss nature w/o talking about endemic poverty which seems foolish to discuss w/o talking about corporations given human agency which seems foolish to discuss w/o talking about colonialism which seems foolish to discuss w/o talking about misogyny,” he writes, while also looking past agency at the world beyond: “In the deepest oceans / the only light is fishes— / luciferin and luciferase mix ribbons flutter in the darkness” (12). The poem offers nature through two ends of an anthropocentric spectrum—the intra-human and the extra-human.

The intra-human exists within and between us, extending the subjective logics of the picturesque and centering individualized experience and perception. For Pico, this subject is not Gilpin’s ideal wanderer, but instead one who has internalized the violence produced by the Romantic impulses of order and mediation. Such nature exists in our rituals and interactions as moments of violence or desire or longing; as the condition of interactions like being propositioned in a pizza parlor or losing consciousness at a dentist’s office. The extra-human includes everything else—insects and deep-sea creatures, stars and space, things that we cannot or do not know. This is a world of wonder, full of moments in which Pico seems to let himself actually love nature, as it ignores and exists beyond human control. Between the intra-human and the extra-human, we might begin to develop new attitudes about nature that maybe be spatialized differently or exert other forces on our designs. There is rich territory between these poles through which we can produce some new design tenants or guidelines.

One—the world is infected:

Our perception of wilderness has evolved as we have transformed nature, leaving us with a question: what is the sublime, now? Perhaps the closest approximation of the fear, awe, and unknowability of William Blake’s tyger, tyger, burning bright, is in the micro: the parasite, the invisible organism, the disease, the insect. “The world is infected / Systemic pesticides get absorbed by every cell of the plant, accumulate in the soil, waterways,” writes Pico (12). Biohazards abound, and architectures of sterility (clean rooms) and artifice are built to ease fears around their proliferation. What if we understood our proximity to the micro as a new kind of blurring of inside and out; a cellularized wilds that we let come dangerously close?

In 2016, Colleen Tuite and Ian Quate of GRNASFCK (now known as Other Fields) built Vector Control, the scene of a “pathogen party” in response to public health officials’ warnings “against nighttime activities in the height of mosquito season.”9 Pathogen parties surely have new meaning in COVID time, but they have other histories and permutations, from children’s “pox parties” to “bug chasers” (people who willingly seek to be infected by HIV typically through unprotected sex). Perhaps we can understand this apparent recklessness by remembering that we enter into the wilderness in order to cure our fear of it. In Vector Control, Tuite and Quate created a controlled pathogen party like a zoo for mosquitoes and their affiliated diseases. Three large semitransparent HVAC ducts wove through windows and interior, and partygoers danced among them. Black lights, CO2, and the ensuing sweat all ideal attractors for the insects, which were held just at bay by the fragile and movable ductwork that contained them.

The project prompts another view of nature and another scale of the affective experience connected to our attraction to danger. For Pico, this is bound up in his DNA: “I am descended from a long line of wildfires / I mean tribal leaders” (43). To invite danger in is to embed this micro-sublime into our building systems and infrastructure, ever closer to the point of contact and potential transgression, past our prophylactic membranes… even past the very idea of architecture.

Two—an abusive relationship with nature:

“It is earthwork as Pop Art, a miniature at full scale,” wrote New York Times art critic Roberta Smith of the Irish Hunger Memorial when it opened in 2002.10 The Irish Hunger Memorial is full of uncanny tensions: there’s a silliness to it, the transplantation (real and imaginary) of a landscape from Ireland into Downtown New York like historical recreation on acid. But there is also something moving in its absurdity, in its location, in the effort of its creation. If Central Park hid its labor under a quasi-naturalistic landscape, here we see the landscape cleaved from its connection to the ground, set atop a mannered design that doubles down on architecture’s artifice.

This cleaving between building and landscape produces an irreconcilability that is beautiful and strange and atmospheric. Nature becomes a disembodied referent that we can understand through Pico: “Revulsion, I thought, was abt self-esteem but now I think might be a warning / Body: don’t get too attached to me” (39). This small memorial is full of jump cuts and jolts, from the details in the paving to the section connecting building to planting, to the backdrop of the Hudson River and New Jersey to the West, Battery Park City to the South, and Tribeca to the East. The site and building and nature all collaged together, equally out of place.

Entering the landscape, seeing fragments of stone walls and tall grasses produces a zombie-picturesque: a displaced graft that creates a scenographic double-take of present and imaginary. There is no stable ground, site, landscape, or context. The memorial is a hybrid of the intra-human and the extra-human, separated by a thin architectural line: a folded surface, a winding path. The combination is romantic and violent. In the poet’s words: “we always find small ways of being extremely rude to each other, like mosquito bites or deforestation / like I think I’m in an abusive relationship w/nature” (22).

Three—I, too, wd like a monument:

Most photographs of Raumlabor’s Floating University reveal an unknowable form. The building is impossible to understand in-the-round. It floats, literally and figuratively, resting on the water—a series of connections, bubbles, and structures all loosely entangled like a tenuous association or a developing collection. “Is life more than a byproduct of nerves?” asks Pico (4). From afar and seemingly up close, the project is all nerves and all interface: prefabricated elements from scaffolds to flotation devices bound together by decking, inflated surfaces, and an endless proliferation of apertures.

The Floating University suggests a series of interiors separated by fields of objects, screens, and circulation. There’s something compelling about its apparent nihilism—a machine floating just on the surface of the water; something specific and defined that doesn’t mimic or reveal its logics. It is a positivist experiment oriented in many directions and asserting its own ground in the artificial-née-natural landscape—a building that is an inquiry, that doesn’t organize or structure or even relate to nature but instead observes it from multiple perspectives that are distinctly anthropocentric.

We could liken it to the Fun Palace or to some high-tech marvel of the 1970s, but it seems oddly at home in the rainwater-retention basin at Tempelhof in Berlin, an abandoned airport now used as a public park. Since the airport closed sixty years ago, the basin has been overtaken by new plants and animals that together make a “third landscape”: a man-made thing reclaimed by nature and made wild anew, reoccupied by the school.11 “Lives flicker, says History / I, too, wd like a monument, says Ego” (6). In this case, the Floating University is a monument to an oscillation between the found and the uncontrolled, wilderness and infrastructure—an intra-human monument, perhaps, looking on at its unexpected landscape.

Four—landscapes of the interior:

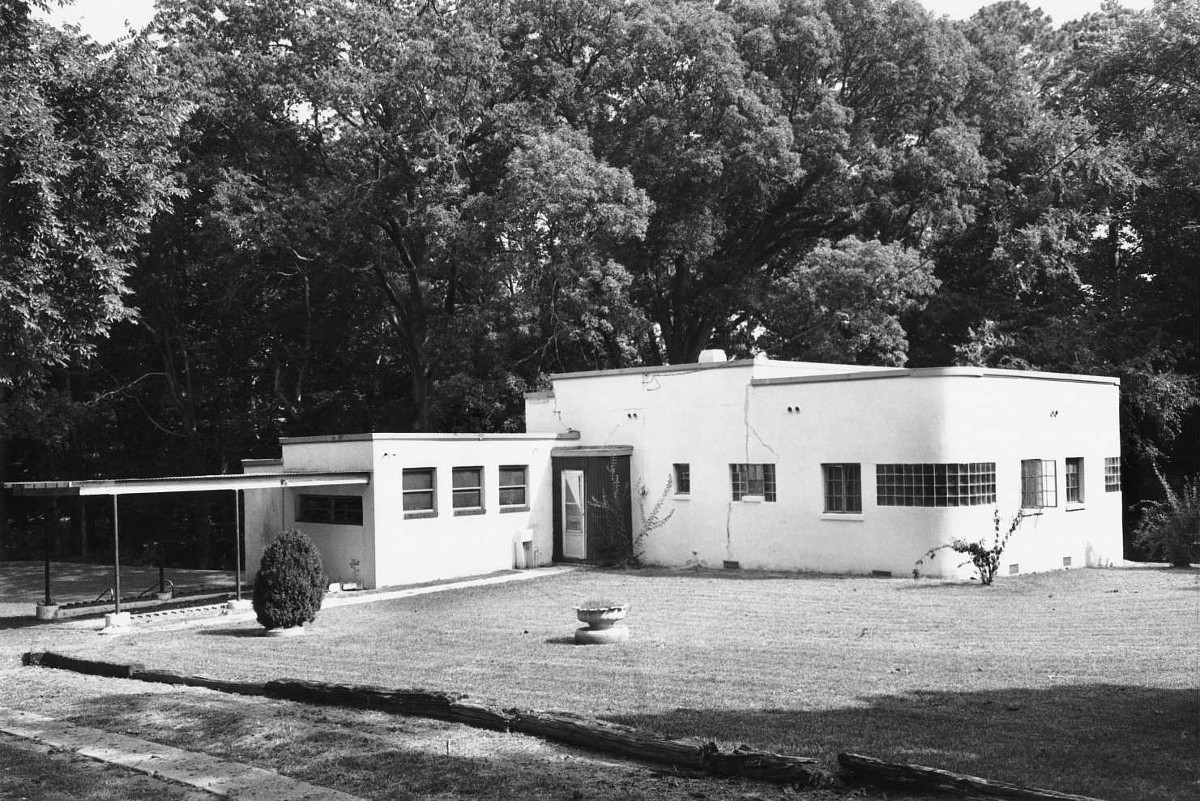

Nature Poem defines nature as the construction of subjectivity itself and explores that subjectivity through its evocations of interiority—“Get in, Loser—we’re touring landscapes of the interior. In the mist of words: the plume the matter the radiant energy”—and creating a world of expansive possibility (50). We can find a disciplinary analogy in Mario Gooden’s rich description of Amaza Lee Meredith’s home Azurest South, which she shared with a “life-long female companion” in Petersburg, Virginia. 12

Meredith was a self-taught Black architect working in the mid-twentieth century. Gooden situates his reading of Azurest South in part through critiquing how Black subjectivity was characterized by Western philosophers as “irrational thought processes and inhuman desires,” outlining the racist ideology underlying Romantic subjectivity.13 Gooden suggests that as a queer Black woman, Meredith designed Azurest South to “confound the hierarchical male gaze and its subject and object relationships” and produce an introverted subjectivity by repurposing the masculinist grammar of Modernism.14 Particular attention is given to the exterior wall and how its use of small windows hides “the reading of the domestic interior and spatial relationships between its inhabitants.”15 The interior was organized to be inward-facing; it was colorful, open, and textured.

There is little description of site, or of context. The house’s introversion speaks to a desire for privacy; a byproduct of the necessary secrecy of a queer relationship. “I like the way my head shivers / restin on yr stomach when you say If I keep hanging out w/u I’m gonna get a six pack / from laughing” (29). Like Pico’s interiors, Azurest South is natural only as an introverted network of relationships, of local desires, and of hidden subjectivity. Here, there is no nature but the purity of the natural itself: that is, what can occur outside of the gaze of power. That formula elides distinctions between inside and out: it mismatches plan and elevation; denies programmatic specificity; and relies on architectural language as a strategic tool of misdirection.

But back to nature, and its representations. Back to the ramble and our Patagonia cruiser. Reversing our tour, we eventually encountered another set of clothes hanging from a tree branch back near the cruising rock, which obscured another scene. Now, two figures: one squatting, visible between the branches from the stomach down, and one standing—familiar textures of reflective banding and mesh, pants and underwear still bunched around ankles. Nature’s representations commingled in that moment: the technological interface (clothes), the picturesque scene (dark nature), the expression of desire (sex) all producing a “scene” oscillating between the intra-human and the extra-human. This is a world hostile to our presence and one that we constantly negotiate through our desires, armed with our technology (clothes, phones, knowledge) but lost among its shadows.

Using Pico’s Nature Poem to reframe how we understand nature can allows us to hone, or at least change how we design alongside, through, and with it. Nature Poem provides a vocabulary to critique the use of nature as a tool of pleasure, of imperialism, and of capitalism. What is the sublime, anyway? “Awe” an extension of our desires, appetites, and individual subjectivity; the “scene” created for our amusement. Accepting nature as more relational, more autonomous, and more uncontrollable opens up new avenues for design that might work between discourses from the ecological to the (a)romantic. A nature made queer through its circuitous paths of desire, violence, and withdrawal—whose expressions might vary beyond landscape, bound together by a slippery ideology forever oscillating between the artificial and the natural, the real and the imagined, the human and the other.

-

William Wordsworth, “Lines, Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour,” 1798, available online at the Poetry Foundation. ↩

-

A short excerpt from Tommy Pico, Nature Poem (Portland: Tin House Books, 2017), 30. ↩

-

Referring to Sebastiano Serlio’s Satirical Scene (“all those things that be rude and rustical”), via Aaron Betsky, who calls the satirical the queerest of Serlio’s three scenes: a site where miracles mix with the everyday. Aaron Betsky, Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1997). This tour was based on research undertaken with my sister, Anjuli Raza Kolb, as part of a commission for the arts organization Triple Canopy, in which we looked closely at Central Park’s history as a landscape and cruising ground. ↩

-

For more information on Seneca Village and to the layered history of the city’s site, see, for example: Diana di Zerega Wall, Nan A. Rothschild, and Cynthia Copeland, “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City,” in Historical Archaeology 42, no. 1 (2008): 97–107; and Eric Sanderson, Mannahatta (New York: Abrams, 2009). ↩

-

This research comes from the New York Public Library’s Ignaz Anton Pilat Papers, as well as its collections on Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux. ↩

-

Adrian Forty, Words and Buildings (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004), 220. ↩

-

Claude Henri Watelet, Essay on Gardens: A Chapter in the French Picturesque (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 26. ↩

-

Roberta Smith, “Critic's Notebook; A Memorial Remembers The Hungry,” New York Times, July 16, 2002, link. ↩

-

Mario Gooden, Dark Space (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016), 128. ↩

-

Gooden, Dark Space, 122. ↩

-

Gooden, Dark Space, 128. ↩

-

Gooden,Dark Space, 135. ↩

Jaffer Kolb is co-founder of New Affiliates and a lecturer at the Yale School of Architecture. In 2018, he edited a special section of Log called “Working Queer” and researches and writes on connections between the built environment and nature, economics, and industrial production through that lens.