The colored woman of today occupies, one might say, a unique position in this country. In a period of itself transitional and unsettled, her status seems one of the ascertainable and definitive of all the forces which makes for our civilization. She is confronted by a woman question and a race problem, and is as yet an unknown or unacknowledged factor in both.

—Anna Julia Cooper, A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South, 1892

The events of Michael Brown’s death and the subsequent upheaval that began in Ferguson, Missouri, effected a call to action in the art world. Many galleries and smaller institutions responded, but larger institutions seemed inadequate in their response.1 It is for this reason that I was so excited to see Chicago artist and architect Amanda Williams’ solo exhibition, Chicago Works: Amanda Williams, at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago this fall. There are many reasons black female art is presently important: the presidential administration’s explicit support of white nationalists; the rise of Black Lives Matter; ongoing threats to women’s empowerment—the list of reasons is endless, while the quantity of exhibitions seems insufficient. The number of anxious and marginalized voices grows in the wake of the existential crises we face as a nation, and, in some sense, there can be no correct curatorial response. But the apparent lack of effort on behalf of major museums underscores the ever-present undervaluation of black female art. This undervaluation perpetuates an institutional and aesthetic bias toward white male artists, which is glaringly obvious to communities of color.

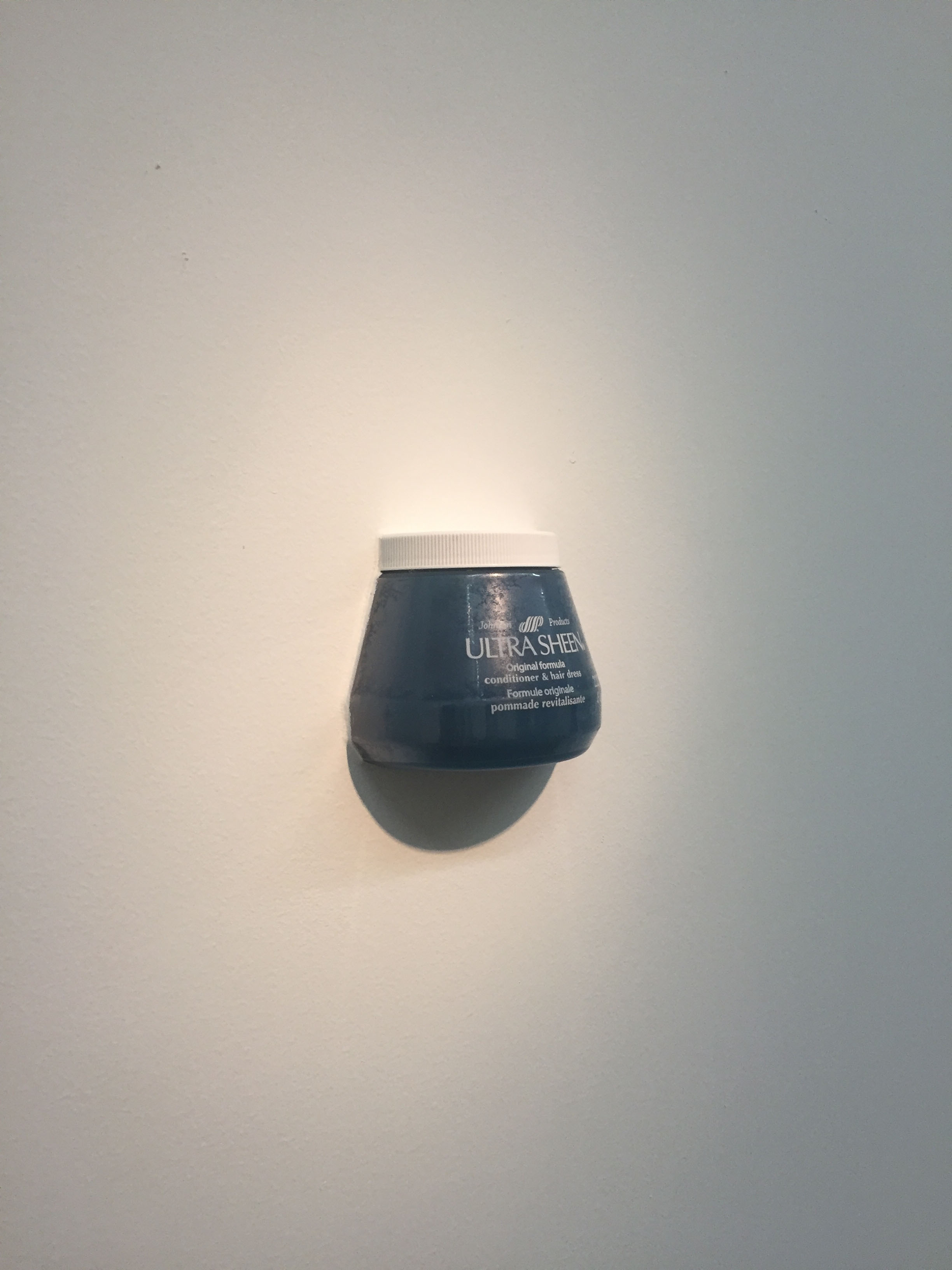

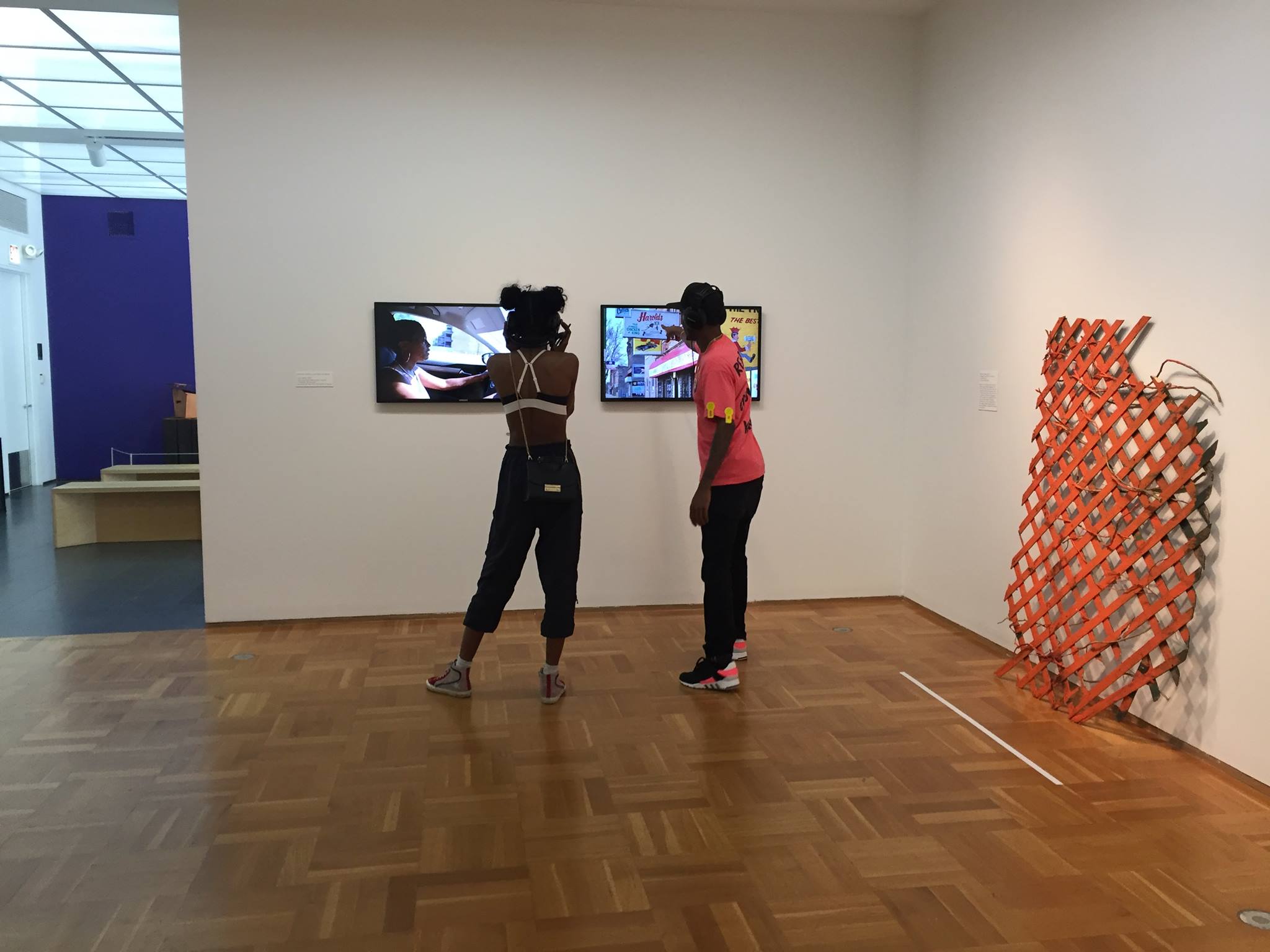

To understand the value of Williams’ works at the MCA, we can read the exhibition as a social gesture of inclusion directed toward Chicago’s largely African American South Side. It is important to understand both to whom this show is important and to whom it is available. Kara Walker’s recent exhibition at Sikkema Jenkins in Chelsea, Manhattan, for instance, traced the atrocities of devaluation but keenly and cynically placed the panels in an exclusive gallery for “Collectors of Fine Art.”2 While Williams’ exhibition at the MCA has not sustained the controversies of Kara Walker’s shows, in part because it is not as bluntly sexual, both artists criticize many of the same institutions that continue to devalue and degrade black women. Controversy is not necessarily the desirable outcome, but placing the artist and audience before the institution is. Representation, both social and artistic, is the ends, but what are the means? Here, the architectural nature of Williams’ work is important. The museum separates the architectural content of her art from its original rich urban context, neatly packaging the critique for its audience. Within the gallery, Williams’ maps, images, and architectural fragments can be easily digested and understood; yes, this is architecture today, the audience agrees. But how is this encounter different from finding an UltraSheen-blue house on the South Side? In situating the work in the museum, we encounter a tepid, Instagrammable architecture, when a more radical curatorial approach to Williams’ work could have demanded more of the observer and the observed.

Creative Destruction

Gordon Matta-Clark, Williams’ architectural and artistic antecedent, famously and desperately tried to flee architectural practice. “You learn to perform according to the rubric, with all the trappings, including kowtowing in front of the cardinals and bishops, receiving the sacraments upon leading the ‘good’ life, and excommunication for heretical behavior...You get the ‘word’...Semper Fidelis,” he said in the 1970s.3 But Matta-Clark was speaking in a different age. Today, to break away from the rigidity of labels is more of an inconvenience than a radical act. Williams’ approach to architecture as art and art as architecture is nonconfrontational to both fields. To hear her speak, it can seem as though architecture is just the most convenient medium—in her case, a ready-to-demolish home that is cheaper than a canvas. But the apparent lightness of Williams’ attitude belies the significance of architecture for her in the same way that Matta-Clark’s disdain for Academic Architecture with a capital “A” belied his own preoccupations with the built environment. What deserves to be preserved, and who decides? This is the subtext of Williams’ work.

Valuable insight into the urgency of Williams’ urban criticism is provided by Ananya Roy:

...I introduce students...not to the innocence of modernism and its heroic protagonists, but instead to what [Paul] Gilroy pinpoints as ‘racial terror.’ The technologies of modern urban planning, be they zoning or preservation, emerged not in the West but in the experimental spaces of the colonies, under conditions of rule and through the exercise of unlimited political power, often action by decree.4

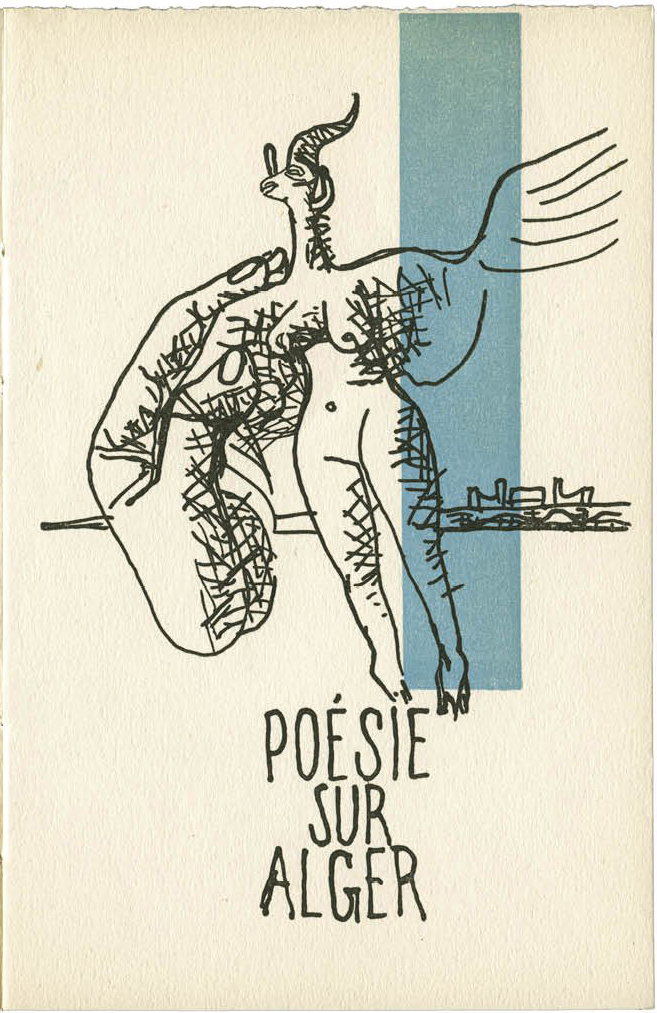

Roy goes on to discuss how the contemporary problem of urban segregation and zoning finds its roots in the modernist ideals of urban planning. She furthers her argument by citing Corbusier’s Plan Obus, specifically “...the sketch that forms the cover of [Corbusier’s] essay, Poésie sur Alger, the hand of the master architect caressing the semihuman, feminized body of the city/colony.”

Corbusier describes cities as a “grip of man upon nature.”5 In his words we read the legacy of modernism as white male colonial practices rendered onto the bodies of black women—both nature and the black female body need to be forcefully controlled. This legacy is perpetuated and preserved in the multiple forms taken by white male privilege today. bell hook’s exegesis on feminism, Ain’t I a Woman?, expands on the grip of white man upon nature and the black female body. It stems, hooks argues, from an anti-woman mythology that allows an identity based on negative stereotypes to be thrust upon black women. Furthermore, she argues, white male power comes from the ability to use and capitalize on technological force.6 This brings us back to Roy’s invocation of “racial terror” and the “technologies of modern urban planning.” What is made evident is that the privilege accumulated across centuries has become institutionalized and writ large onto our modern domestic lives.

Williams renders this heritage visible in the angst of the lonely, chromatic houses of her Color(ed) Theory series, which forms a major part of the Chicago Works exhibition. Knowing the urban planning failures, lack of economic equity, and lack of social capital that gave rise to the houses’ impending demolition, we can read Color(ed) Theory as a bold response to the exploitation of the black home, which is, in turn, a metaphor for the exploitation of the black female. That the first works in Color(ed) Theory are painted to match and then titled after black beauty products is notable. Williams describes the process for finding the colors of Englewood identity as a casual brainstorm with her friends, in which she threw out colors and they responded “yes” or “no.”7 The colors register immediately in the neighborhood, where a discarded package of Newports might sit next to a crumbling Newport-green home, slated for demolition. With this shared palette, the neighborly collaboration of every house painting was a local and ephemeral act of reclamation. Captured in the museum as a series of photographs and short films, however, they become neatly packaged and summarized events. The audience is given enough to acknowledge the content but not enough to understand the context.

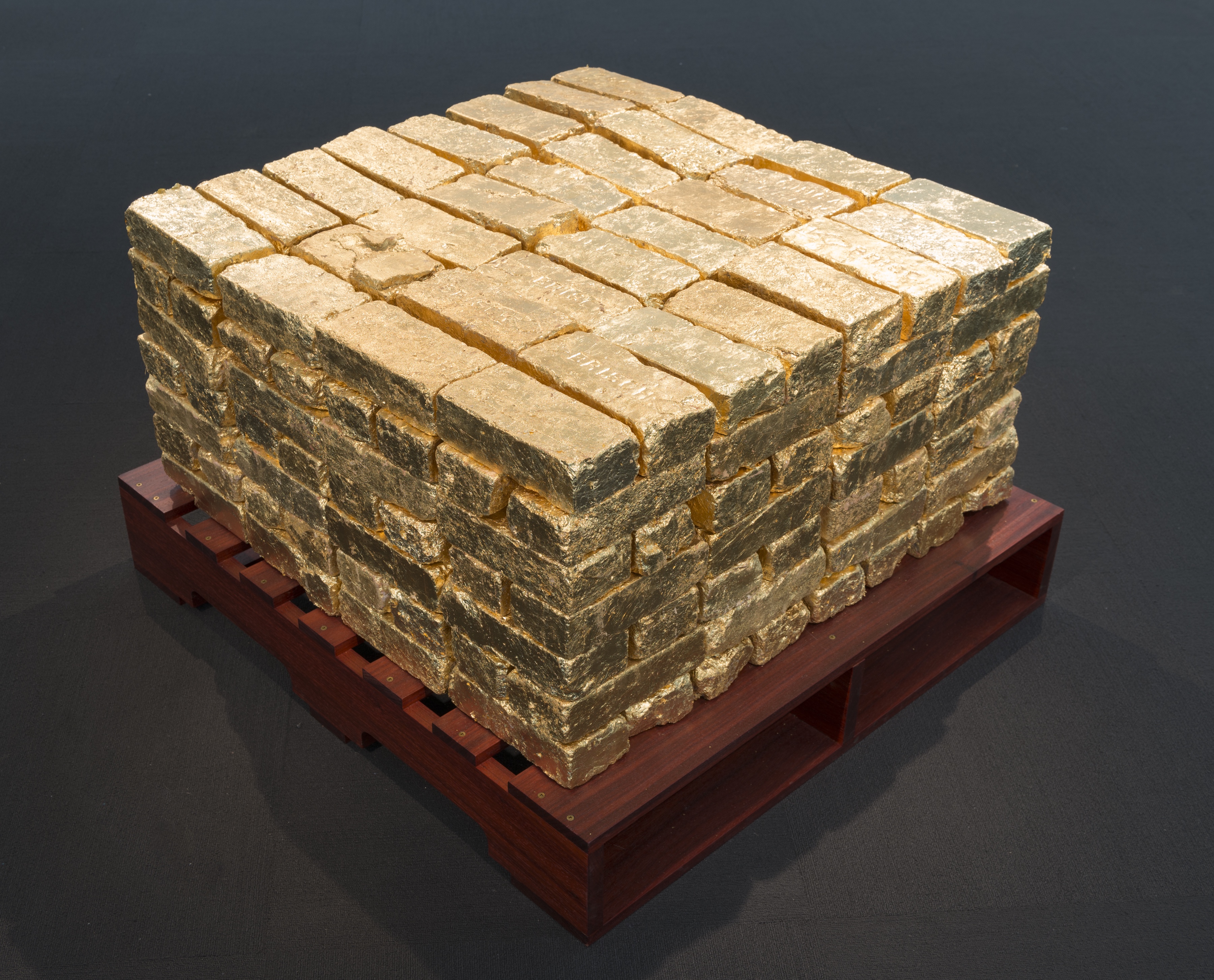

Gold is alluringly portrayed in several ways throughout the exhibition—positioned in the center like an open treasure chest or glimmering from behind a corner, just out of reach. The accompanying text acknowledges the value of this color, describing “material values and abstract notions of success” as well as ideas of “gaudiness and excess.” However, after having attended several of Williams’ lectures, it seems like the gold used in her work can mean so much more. A piece like It’s a Gold Mine/Is the Gold Mine? feels so much richer for the urban context from which its material was drawn (the bricks of demolished Chicago houses). But a site-specific piece built for the museum setting, like the gold-drenched room called A Dream or Substance, a Beamer, a Necklace or Freedom? looks contrived—so much so that it seems a little less brilliant under the pale-blue lighting of the awkward room surrounding it. Presented in the level field of the gallery, the two gold-covered pieces read as equally valuable, with the salvaged brick reduced to the same level of meaning as the new drywall.

Williams is quick to cite Vitruvius’ core elements of Firmitas (firmness), Utilitas (utility), and Venustas (delight) as invaluable to her work. These qualities can all be traced as sources of economic value. When Williams paints brick gold, she is effectively critiquing the value traded at the expense of black communities. In Chicago, where common brick is carefully preserved by black workers, the exchange is crucial. The brick is salvaged because it is valuable, but Williams’ piece asks us to consider who controls that value and why it is ascribed to rubble but not South Side family homes.8

Williams’ fragments, salvaged from demolition sites, draw the urban context into the museum. We can understand their power thanks in part to recent studies exposing the long-lasting effects of redlining practices in the 1930s, which give us a sense of the true meaning of the word “blight.”9 As Brentin Mock writes, “The word ‘blight’ might only be a more polite way to say ‘ghetto’—another word that no longer has one universal definition, but we all know what it is and who it is when we see it. Such terms have historically been applied mostly to spaces where white, Christian families don’t live.”10 By using homes slated for demolition as the material basis of so much of her work, Williams is commenting on institutionalized segregation—in particular, the blight, the neglect, the systematic refusal to provide for Chicago’s majority–African American South Side what is provided for the city’s majority-white North Side. In the case of the exhibition, these fragments should speak louder than words. Instead, they are blocked off, marked with that untouchable quality of museum pieces—put on display and not to be handled, though they were once part of a home, part of a collaboration, and part of a demolition. The vibrant fragments of Englewood, so heavily marked by racial, political, and social acts, are now preserved as sculptural objects, removed from the system that fostered their creation and destruction.

To borrow Joseph Schumpeter’s term, the “creative destruction” that tears down one group in an effort to enrich another is as prevalent today as it was in the 1970s heyday of UltraSheen.11 White women borrow freely from black women—as seen in the casual appropriation of “ratchet culture” and cornrows—but the opposite is almost unthinkable. hooks again clues us into the heritage of white female appropriation of black female aesthetics. The relationship between black women and white women, according to hooks, is rooted in the hierarchy of slavery. A mutually antagonistic relationship emerges, in which both groups feel envy and distrust for each other, though skin color privileges white women. As a result, casual appropriation of black beauty allows white women to don the aesthetic of black women without having to live the realities.12 It follows then that Williams’ beauty product pieces particularly speak to black women. UltraSheen is a product for black women that white women cannot appropriate because they will never have an experience of the reality of black hair. When Williams presses an UltraSheen jar into a wall, she is elevating a product created by black entrepreneurs for an exclusively black market to the status of a work of art.13

To encounter an icon of black female identity, with all its weight and burden, projected into the very architecture of the museum, is revelatory in the sense that it forces a white audience to consider a black narrative. Likewise, the Greener Grasses fragment from the Flamin’ Hot Cheetos house carries in the redlines that engendered blight upon a neighborhood for generations. What is so challenging about this museum experience of Williams’ work is that the ephemeral is forced into a permanent and preserved state. The accompanying videos in the exhibition suggest that Color(ed) Theory houses were not created in angst, though their photographs suggest it. The video documentation shows a lively neighborhood coming together to partake in a fun activity. That the paint they’re using is Flamin’-Hot-Cheetos red is an inside joke or tongue-in-cheek statement shared by the community, not a loaded commentary on obesity, food deserts, and problematic taxation. In a museum setting, however, we can read the remnant of the building academically. The fragment cannot force us to read it as we would in Englewood. We can impose upon it our own cultural understanding of how to read museum pieces.

Curating Destruction

The curatorial approach to the exhibition is especially important because Williams co-curated this edition of the Chicago Works exhibition series with Grace Deveney, a curatorial assistant at the MCA. The decision to include the artist as curator is part of a larger discussion on the expanding role of curatorial practices. Here, Paul O’Neill’s consideration of how these roles fit within the wider history of curation is helpful:

...forms of communication are actively produced and maintained from within the social and cultural field of art by all those who have an investment in it. Further, artists and curators are cooperative producers of culture, regardless of what it is that distinguishes their mode of agency...Hence both artists and curators partake equally in the resistances, conflicts, and divisions that run through the field of cultural production as a whole.14

What we see in the Williams-Deveney joint venture is that an artist and her coterie of collaborators are entering Chicago’s North Side, a space that continues to be culturally and ideologically segregated from the city’s South Side, and placing pieces of their neighborhood—pieces of their lived experience—onto the walls of a world-class museum.15 They are bringing their narrative to the space. This act creates a dual concern for the curator/artist team in that it automatically sparks an unspoken dialogue between the pieces and the institutional building, as well as leaves behind the surrounding struggle in which the works participated and were brought to life.16 Once again, we can turn to O’Neill:

The curator is recognized as the agent responsible for the exhibition as an object of study and experience, and is no longer perceived as merely a part of a chain...[I]nstead he or she is seen to be responsible for extracting art from its position or circulation, opening up a space where individual works of art gather new meanings and values by virtue of their regrouping for public consumption.17

It seems to be in this repackaging for wider public consumption that Williams’ works lose their edge. Bachelard’s Poetics of Space accounts for this loss when he writes, “the positivity of psychological history and geography cannot serve as a touchstone for determining the real being of our childhood, for childhood is certainly greater than the reality.”18 The memory of the events that transpired to create Williams’ work is so much more than the evidence left behind for museumgoers. By entering the MCA, the real being of the fragments is indexed and preserved. A new reality is created for them that allows for the shared conviviality, the shared inside joke of UltraSheen, to be acknowledged by a major cultural institution.

The division between South Side neighborhoods and the Gold Coast museum amplifies issues like site context. In particular, it asks a lot of the architectural components of the exhibition. A fragment of a broken fence, for example, is radically altered into a piece of art.19 The accompanying video made for the installation is an insufficient means of accessing the place of the fragments’ origin. Elisabeth Sussman writes about Matta-Clark, “[W]e have to grapple with what DeBord calls a ‘rather pleasing vagueness’...[The works] had an immediacy at the moments of their making made especially poignant by the fact that they were experienced by a relatively limited number of viewers. Those of us who have come later have to experience what Matta Clark left behind.”20 The same ephemeral quality permeates much of Williams’ work. There is a sense that the museum audience has missed the spectacle and only arrived for the afterglow.

What this mutable experience reinforces is that the museum is not the site of the spectacle but rather the site for the intellectualization of the spectacle. It is a nuance that situates the exhibition in an uncomfortable space, for while the artist can evolve her own relationship with her collaborators and neighbors, the museum appears to be exploiting the social tensions in place as a result of its cultural practices. Namely, the museum appears to excise the pieces of detritus from their South Side landscape to further its own agenda as a forward-thinking institution. It can exhibit both Takashi Murakami and Williams in the same month because it does not expect the exhibitions to be in conversation.

O’Neill presents an alternative curatorial approach that could have produced a different result: “[a] more ‘relational’ and socialized counterstrategy...in which the curator resists the exhibition as a closed-off event-oriented experience by evolving an exhibition-making process through conversations between works, artists, and viewers.”21 To the MCA’s credit, under Madeleine Grynsztejn’s leadership, it has sought to address this imbalance through efforts like free public conversations with the artist, children’s art days, social media outreach, and a “touch tour” of the exhibition. However, walking through the exhibition begins to feel like cultural tourism—to be able to pass through for personal entertainment, without having to consider the baggage. It is easy for the museum visitor to take and post a picture on social media and feel like they participated in the site of the exhibition and encountered Englewood. Uncomfortable situations have resulted, for example, in which white women post on Instagram about their children learning about the “whole concept of an abandoned house” from the exhibition.22 In permitting the difficult experiences of black women to be read as self-exploratory white urbanism, the museum fails the fragments. It suggests what Kate Derickson has coined “the unbearable whiteness of geography.”23 That the “whole concept of an abandoned house” must be explained through a museum exhibition, far removed from the conditions of actual abandoned houses, and far removed from the conditions of blackness, is at the core of the “rather pleasing vagueness” that bothers me about the exhibition.

The exhibition can and should demand more from the viewers. In conversation with president and CEO of United States Artist Deanna Haggag, Williams was pleasantly defiant when asked how she addresses different audiences. “I don’t!” she responded with a shrug.24 But this is where I found the major pitfall of the exhibition. It explains enough so that Williams’ unintended audiences feel like they get it but does not go far enough to actually allow them to understand the context and therefore question their own role in the shared issues it raises.

Finally…

Architecture plays an essential role in ordering physical space and in reflecting cultural identity...[O]ver time it has become more and more vital for neighborhoods like Harlem to protect the cultural and aesthetic significance of the many historical and social values there by preserving the neighborhood’s architecture.25

Spaces and places have an identity of their own. In a city like Chicago, neighborhoods pride themselves on their hard boundaries, and neighborhood pride often barely veils the ethnic pride at its root. As the current presidential administration has repeatedly pointed out, Chicago is a liberal city playing fast and loose with racial politics. The MCA is clearly working to broaden its scope and engage with contemporary radical discourses. But outside the walls of the museum, segregation is still strikingly visible in the city, and the legacies of the Great Migration, white flight, and redlining continue to play a painful role in the resources promised and granted to each neighborhood. Single exhibitions cannot remedy the past. But on the road to the systemic, radical changes that are urgently needed, elevating black female voices like Williams’ and encountering the unspoken yet glaring gap between Englewood and the MCA is a necessary step.

-

The inadequacy of curatorial responses is the topic of digital conversations like #museumsafterferguson, an ongoing Twitter and Instagram project; The Incluseum, a blog that encourages curatorial dialogue and critique; and groups like Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter. ↩

-

Kara Walker: Sikkema Jenkins and Co. Is Compelled to Present the Most Astounding and Important Painting Show of the Fall Art Show Viewing Season!, New York, Sikkema Jenkins & Co, September 2017, link. ↩

-

Spyros Papateros, “Oedipal and Edible,” from Gordon Matta-Clark: “You Are the Measure” (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2007), 72. ↩

-

Ananya Roy, “The Infrastructure of Assent,” the Avery Review 21 (January 2017), link. ↩

-

Le Corbusier, The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning (New York: Dover, 1987), xxi. ↩

-

bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman? (New York: Routledge, 2015), 86. ↩

-

“Amanda Williams in Conversation with Deanna Haggag,” talk, MCA Chicago, October 17, 2017. ↩

-

Brick salvaging in Chicago is a loaded and racially charged operation. For more on Chicago common brick history and race relations, see Tori Marlan, “Brickyard Blues,” the Chicago Reader, January 21, 1999, link. ↩

-

Daniel Aaronson, Daniel Hartley, and Bhash Mazumder, “The Effects of the 1930s HOLC ‘Redlining’ Maps,” Chicagofed.org, 2017, link. ↩

-

Brentin Mock, “The Meaning of Blight,” CityLab, February 16, 2017, link. ↩

-

For Schumpeter, “creative destruction” was about one process that was torn down by a new process in order for the latter to grow. For our purposes we can read that as the dominant financial and commercial success of the white beauty industry using black beauty products and aesthetics while not actually catering to black consumers. See Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (London and New York: Routledge, 2003). ↩

-

In a 2014 article from the Los Angeles Times, Jon Reyman, a Los Angeles hairstylist, said “cornrows are moving away from urban, hip-hop to more chic and edgy”—where “urban, hip-hop” can be read as “black” and undesirable and “chic and edgy” can be read as “white” and desirable. This description of cornrows highlights the way in which appropriation can be considered a laudable endeavor. See Ingrid Schmidt, “Head-turning Hair Fashions for Fall: Bangs, Rows and Tails,” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 2014, link. ↩

-

Anecdotally, several women near me at the exhibition immediately described the Proustian effects of their encounter with “Be the Girl with the Turned-on Hair.” ↩

-

Paul O’Neill, The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s) (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012), 102. ↩

-

In an excellent piece on an early MCA project, Rebecca Zorach asks us to “try a somewhat brutal exercise...take the table of contents of Art since 1900 as our guide to what’s considered important in the twentieth century by art history now...Looking at the chronological table of contents, we would think that African American artists were absent in the fifty years between 1943 and 1993, and that the one thing that happened in art in the entire twentieth century in Chicago is that László Moholy-Nagy died there.” Zorach further argues that the result of this “segregation of knowledge” is simultaneously a mirror and reproduction of a “persistent segregation of artist and activist communities.” See Rebecca Zorach, “Art & Soul: An Experimental Friendship between the Street and a Museum,” Art Journal Open, September 4, 2011, link. ↩

-

Recently Amanda Williams has used the term “thrival” rather than “struggle for survival.” See for example her comments at the “Public Gestures” symposium held at SAIC’s Leroy Neiman Center, November 18, 2017. ↩

-

O’Neill, The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s), 97. ↩

-

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 16. ↩

-

See the above image of Williams’ Greener Grasses. ↩

-

Sussman, Gordon Matta-Clark: “You Are the Measure,” 14. ↩

-

O’Neill, The Culture of Curating and the Curating of Culture(s), 120. ↩

-

Images of social media posts were omitted from this piece to protect the privacy of individuals, but a simple search of #amandawilliams or #MCAChicago will reveal a trove of selfies. ↩

-

Roy, “The Infrastructure of Assent.” ↩

-

“Amanda Williams in Conversation with Deanna Haggag.” ↩

-

Karen Abrams, “Hijinks in Harlem,” the Avery Review 24 (June 2017), link. ↩

Tizziana Baldenebro is an MArch candidate at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She graduated from the University of Chicago in 2010 with a B.A. in anthropology.