“Please do not move.”

The photographer Abbas Shirmohammadi opens the shutter. Thousands stand quietly, waiting. The United Center in Chicago stops as Shirmohammadi makes the official photograph of the 2024 Democratic National Convention. From the floor, I watch him pan the century-old camera around the room, counting the exposure time. At exactly twenty-two seconds, Shirmohammadi places the cap back on the lens.

“Congratulations to all,” he concludes. The space roars back to life.

The photograph will later be displayed at the DNC gift shop, alongside other photographs of past conventions, all strikingly similar1: a wide panorama of the arena, with thousands of attendees surrounding a stage adorned with lights, logos, and American flags. An empty podium stands in the middle, waiting for another round of speakers. Photographed from meters above, the circular room is flattened. The faces of the individuals are no longer discernible. Rather, their bodies converge into a single mass, drawing attention to the crowd itself.

While keepsakes for those in attendance, Shirmohammadi’s images carry a much more subtle yet significant message: They capture the “will of the people”—the foundational principle at the core of “American democracy.” The assembly signals a unified popular sovereignty, which the party needs in order to legitimize its authority. Photographs disseminate the event for the rest of the American public to bear witness, and thereby, reaffirm.

Yet what these photographs do not convey is the orchestration of popular sovereignty. Or rather, how sovereignty is conditioned by a set of spatial controls. Judith Butler describes this mechanism of control as the “spatial organization of power”—“an operation of power that works through both foreclosure and differential allocation.”2 Just as the photographer controls the parameters of the image—framing the spatial field, adjusting the exposure, focusing the lens, choosing what to crop out and when to release the shutter—so too does the party control the spatial parameters in which the image is made, ultimately shaping the visual narrative of popular sovereignty. By restricting the “spatial locations in which and by which the population may appear,” the party regulates “when and how the ‘popular will’ may appear.”3

This spatial organization of power is evident at the US national conventions, which thousands attend over the course of four evenings. First held in 1831, the nominating conventions were seen as a means to make “American democracy more representative and more deliberative.”4 As the conventions have grown in size and complexity every election year since, each party’s national committee chooses a host city based on economic, logistical, and symbolic factors.5 To accommodate such large assemblies, the conventions are often held in sports arenas, where party organizers decide who is and is not allowed to assemble. They control who is and is not allowed into and throughout the venue, allocating color-coded credentials that not only permit entrance but restrict movement between segmented enclosures. The party stages the events and sets the discourse—the lineup of speakers, the words on the teleprompter, the timing of each act, the entertainment between sets, the lighting for dramatic effect. Even the audience is brought into this “orchestrated enactment,” holding signs that correspond to key talking points—provided by party volunteers throughout the night—becoming themselves a prop to frame the party message.

At its national convention in Milwaukee in 2024, the Republican Party constructed a narrative of then-former president Donald Trump as “touched by God” after his near assassination, using his white ear patch as a rallying cry for solidarity. This “divine” narrative was, of course, strategic. In focusing attention on Trump, it created a “gaze-directing regime”6 that distracted supporters from major policy changes to the Republican platform—changes brokered on the periphery of focus, on “the edge of sight.” Meanwhile, at the Democratic National Convention held in Chicago—home to the largest Palestinian community in the country—the Democratic Party staged a televised narrative of inclusive coalition building that disregarded the voices of Arab Americans who were demanding that Vice President Kamala Harris end Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza and assault on Lebanon. Left outside, or rather cropped out, were the uncommitted delegates and protesters who faced multiple barriers to entry, both figuratively and literally. These boundaries define who is accepted into the body politic—the space of discourse, ultimately limiting the diversity of thought, of expression, of true joy,7 and deep grief—a sweeping range of identities that the Democratic Party purports to include but in practice denies.

Policing the boundaries of participation, curating the assembly, and staging enactments works to ensure an image of party unity that obscures the struggle for dominance and the strong-arming of policy. It ensures that the image of the party’s presidential nominee—whether small-town mayor, freshman senator, federal prosecutor, or even convicted felon—is celebrated as an accomplishment of the electoral process rather than the party intervening behind the scenes. The national conventions are not spaces where power is granted by the people but spaces where power is made by the parties themselves, and images work as agents in that power-making. As Butler reminds us, “assemblies are orchestrated by states for the very purpose of flashing before the media the popular support they ostensibly enjoy.”8 Simply put, the conventions are public relations events to self-legitimate power, and photographs are used to spin and circulate the party’s narrative framing.

Yet it is not only a figurative framing of the narrative but also a physical framing of the photograph that those in power condition. Photographs are restricted by the spaces in which they are made. An image relies on the physical architecture and infrastructure to hold the photographer and the camera, which are becoming ever more chained to the conditions set forth by those who control the space. If a photograph “captures” the photographer’s present reality, then reality is whatever the party makes it. Here at the conventions, the borders of the photographic frame are policed as strictly as the boundaries of participation, working to shape every image regardless of who makes it: a spectator in the crowd, a social media influencer, or a press photographer.

Through my press credentials with the Wall Street Journal, I was given access to this space of power-making—a space that conditions the visual frame and self-legitimates authority. It is in this space of struggle, of contradictions, of tension and pressure—where all levels of local, state, and federal government converge for one time only, bringing into view the machinations of American power—that I am tasked with photographing. Documenting what I see, my objective falls under the larger mission of the press: to pull apart the tangled layers of our political system, to expose the creeping shadows emerging from the smoke-filled rooms of Washington, and to hold power to account. But such a mission must also turn inward to critique the media’s own role in aiding those in power, as we have seen repeatedly when party talking points are not fact-checked, misleading headlines are written in passive language, and those with lived experiences are passed over for anodyne government statements.

As a photographer, I am not immune to this spatial organization of power. And yet, as I navigate these spaces of control and learn the techniques with which visual dominance is asserted, I find methods for countering the party framing even as I work within its parameters. In fact, photography may operate within existing structures to subvert them—opening up the possibility of resisting through aesthetic and discursive interventions. Images can work as agents of power-making, but they can also work against the rhetoric of those in power. They are two sides of the same coin—a tension I work through, with, and against at the national conventions.

Focusing the Narrative Frame: The Republican National Convention

“Keep it moving.”

Two men wearing “Trump 2024” hats shout to keep the aisles clear. I am standing against a wall on the convention floor of the Fiserv Forum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, when a woman in the crowd approaches and asks if I would like an ear patch. I respectfully decline but ask if I can make a photo instead. She pulls out two matchbox-sized American flags from a clear plastic bag and flips one over. “We ALL dodged a bullet,” it reads, with the name and website of the businessman who made them. Karen Tirio, an Illinois delegate, had 1,500 paper ear patches shipped to Milwaukee for the last day of the Republican National Convention, where she was distributing them for free.

In a private box reserved for his family and closest allies and overlooking his supporters, Donald Trump wore a large white bandage on his ear9—a reminder of his near assassination. He made sure this white bandage was always on view, centering the spectacle of himself as the focus of the crowd’s gaze and of the photographer’s lens.

The Fiserv Forum is a circular arena with tiered seating and multiple viewing platforms.10 From the front and side risers, photographers were granted unobstructed views of the space, to make clean, sharp, focused images of the speakers, the spectators, and Trump. This visual accessibility is, of course, no accident: Party organizers anticipate the images made at the event, constructing risers and assigning photographers' positions accordingly,11 while a physical and digital media infrastructure, which also includes private studios, workstations, and advanced technologies, facilitates the hundreds of publications that disseminate images of the event throughout the week. The Senate Press Photographers Gallery, a nonpartisan federal office at the US Capitol,12 is tasked with handling the entirety of the photographic logistics. Acting as a liaison between the party organizers and the media organizations, the Senate Photographers Gallery works to create spaces throughout the arena that offer the best vantage points and to secure more media access to the convention floor, which party organizers are often reluctant to give.

Stationed on the risers for the entirety of the event, photographers are physically tethered to cables rapidly transmitting images from their cameras to their editors backstage, while cameras installed in the arena’s rafters—triggered by remote or set timers—capture a panoptic view of the space. These positions, set above the crowd, aim to force an aerial perspective that parallels Shirmohammadi’s panoramic images, where the bird’s-eye view abstracts the arena, “melting” the individuals into a “single great body.”13 The physical act of looking down onto a circular space where the photographer can “see constantly and recognize immediately”14 holds a certain power over the crowd, one that Michel Foucault addresses through Jeremy Bentham’s architecture of the panopticon.15 It is an “invisible power in the service of subtle coercion,”16 where the spatial limitations of the panoptic room force the bodies into the photographic frame, subjugating them into the role of “the masses.” Images edit and select “what and who will count” in the frame, constituting who “the people” are, even when that designation “works through delimiting a boundary that sets up terms of inclusion and exclusion.”17 While tightening on the expressions and performances of individuals in the crowd might create a moment of individuation, when those images of anonymous spectators are used alongside stories relaying the course of events, that individual becomes the paradigm of “the people,” generalizing the collective experience.

With no assigned position, I am put into a floor rotation with dozens of other photographers, giving me access to the delegates and guests. As these rotations are timed, lasting up to one hour, I am always aware that, without a fixed position from which to observe, I might miss key moments on stage. Yet, I am untethered and mobile, not under the party’s direct gaze or control, which affords me some freedom to see the crowd up close.

Those on the floor see us too and come ready to be photographed. As if rehearsed and choreographed, they wave their hats in perfect unison—chanting, shouting, singing, and booing—playing to the cameras. To be “caught” in a photograph, to be recognized on television, on the arena’s video cube, or in a viral social media post, is to be seen and made visible to others, though even more importantly, it is to be seen by the “heroes of the game,”18 in this case, the party’s presidential nominee. The attendees are no longer controlled solely by the camera’s omnipotent and ubiquitous gaze at bird’s-eye view. Rather, they become willing participants in the disciplinary work of the panopticon, subtly coerced by the presence of the cameras through “the promise of being part of a community of exposure.”19

One by one, party loyalists take the stage and speak of the attempt on Trump’s life—“saved by God to redeem America”—praising his courage and propping up his messiah-like image. Each speaker is tasked with keeping to the party message, focusing the audience’s attention on Trump, and building anticipation for his direct address to supporters. When the time does come on the final evening, Trump recounts his “divine intervention.”

With hands raised in praise and heads bowed in prayer, the attendees in the arena fall silent. Working his congregation like a pastor of a megachurch—validating his supporters’ faith in God and “the righteousness of his mission”20—Trump appears onstage as the triumphant “sovereign.” It is at this moment that, as Foucault states, “the role of the political ceremony [is] to give rise to the excessive, yet regulated manifestation of power.”21 In other words, the convention ceremony affords Trump the opportunity to present himself, to perform power, thereby creating himself as the image of power.

This image of power relies on yet another image, made a few days earlier in Butler, Pennsylvania, by pool photographers documenting Trump’s campaign rally moments before and after the gunshots.22 Standing at Trump’s feet that day was Associated Press photographer Evan Vucci, who photographed the moment Trump was carried off the stage by Secret Service agents—blood licking the side of his face, his fist raised in performance for the cameras.23 Their bodies dominate the photograph’s frame while the background is free of distractions, except for a large American flag waving overhead—strategically placed by the campaign at the start of the event. If anything, it was Vucci’s image that was the real divine intervention for the Republican Party.

While campaigns are not permitted to use editorial images for political use, this (and the multiple iterations of the image made that day) frames a holy narrative of Trump as ascendant, elevated through suffering, having just survived an assassination attempt. These images are projected onto the convention stage where the architecture of the arena reinforces an “aural quality,” directing the gaze of his supporters toward a central point, similar to that of a religious ritual where worshipers pray facing the church’s altar. Instead of gathering in reverence to a Higher Being that is beyond sight and beyond the physical building of the church, the circular, tiered spatial configuration of the arena allows each other to be seen, revealing “the crowds not only to their adored heroes... in the centre, but also to themselves.”24 Both the space and the party work to bring Trump's supporters into the projected narrative of the images, a narrative of the “we.”25

As the ear patch reminds us: “We ALL dodged a bullet.”

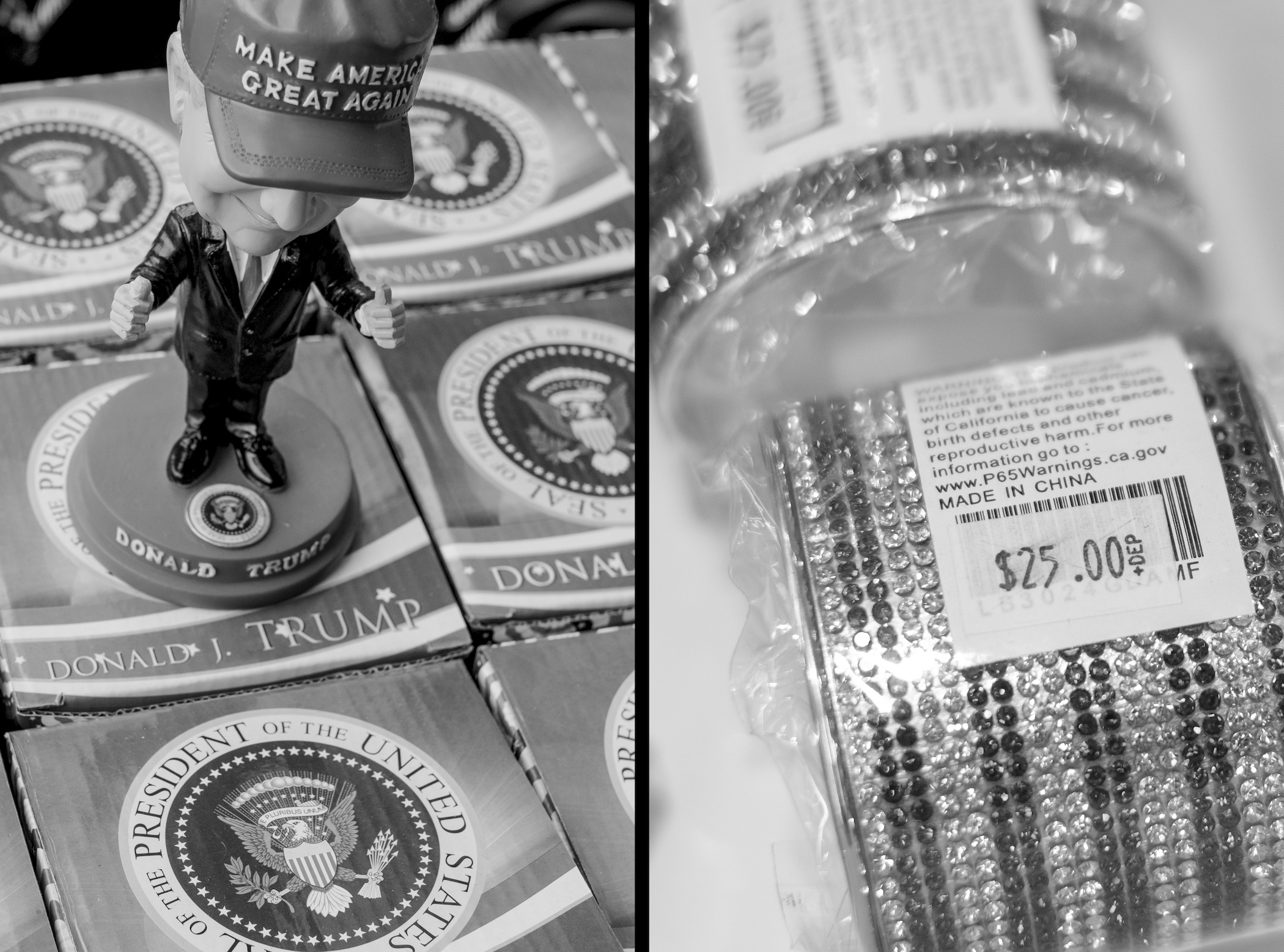

I made my way to “Convention Fest,” the street festival–cum–circus sideshow, located just outside the arena within the barricaded perimeter—a space accessed only by those with credentials. Rows of market stalls lined the streets where local businesses, like Randa Fahmy’s Makeup America,26 sold and marketed their goods and services. As I moved between these stalls, I photographed women sifting through boxes of Republican-themed plastic jewelry at the official RNC gift shop—all made in China—and browsing for shirts that read “I’m voting for the convicted felon.” Printed and framed, Vucci’s photo stood next to a stack of Trump Bibles selling for $75 each.

I watched MAGA supporters sitting behind the president’s Resolute desk in a mockup of the Oval Office and men signing a large pink bus supporting anti-abortion. Some took selfies in front of a one-room schoolhouse—a nostalgic reminder of the Republican Party’s simple origins (and selective amnesia for a party set on closing the Department of Education). Others danced for videos sponsored by the Heritage Foundation and entered an AR-15 giveaway hosted by the US Concealed Carry Association.27 Members of the Trump family came to sell and sign books. Pop-up studios interviewed politicians and party celebrities on their talk shows, which convention goers could watch and participate in, from a roped off distance.

Organized by the RNC, everything at Convention Fest was intended to entertain; to propagandize; to fundraise for the party and by extension, for Trump.28 The party narrative of the “we” expands into this open-air market—again, a space just outside the arena but within its heavily policed perimeter. The spatial arrangement of Convention Fest creates the illusion of choice (and, perhaps, of free movement), when none other than support of the party message exists.

Ending just at the metal barricades, the convention complex is bordered and framed like a photograph, and just as photographs can bring “more into view, they [can] also reinforce the invisibility of some things by overtly focusing on others. What is not represented is further obscured.”29 In this way, the space is not only a means of promoting the message but also a tool for distraction, drawing attention away by hyperfocusing on the party narrative and entertaining their supporters. It is this space outside the frame that becomes just as significant as the space within it, raising the question: What is obscured and hidden beyond the convention frame, at the periphery of focus?

Three miles away from the security perimeter, a private lunch was held at the Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museum, an Italian Renaissance–style house on Lake Michigan. The Iowa delegation was hosting an event with former Speaker of the House and Republican stalwart Newt Gingrich on the last day of the convention. An assortment of pies sat underneath a painting of the goddess Athena, while a woman wearing a Trump 2024 hat played the piano beside a Madonna and Child. In a rarity, I was the only photographer at the event. I was told I was free to move about the villa, where I photographed former Speaker Gingrich with his wife—the former ambassador to the Vatican Callista Gingrich—as they spoke with party officials and plated food at the buffet, dining outside on the veranda. It was a blisteringly hot day.

Florida governor Ron DeSantis walked in and I was immediately met with a hand to the camera. “No photos,” warned a staff member. “The governor does not want to be photographed before he speaks.” Governor DeSantis had come to raise his profile with the Iowa delegation, a custom for the ambitious aiming to run in the next presidential election. His speech was quick—the same stump speech performed on his failed primary race—and his exit even quicker. He took no questions. This was one of many Republican networking and strategizing events taking place throughout the week, held on the edges of the conventions and mostly closed to the press. Hosted by state delegations, political organizations, and corporations, these events work to shape policy, create partnerships, recruit party organizers, train volunteers, and most importantly, win elections.30

Former Speaker Gingrich stood up to speak. Like everyone else before him, he opened by praising God for saving Trump’s life before turning to the Republican platform, which he commended Trump for cutting. “He didn’t listen to anybody. He literally, and personally, went through it and kept editing it down,” Gingrich said of the new platform.31

It was a forced departure from tradition. The party platform is normally drafted, debated, and ratified by the platform committee made up of volunteer delegates from across the country at the beginning of convention week. Yet this time, they were told the draft would be ratified as is. Trump and his party operatives steamrolled any opposition or proposed amendments to the draft, locking their delegates into a room with no outside communication until their version was passed.32

“This tells you where he wants to go,” Gingrich foreshadowed, laying bare a blueprint of Trump’s next four years in power. Behind closed doors and away from public sight, the party operates with little resistance, evading scrutiny and accountability. Sequestering themselves outside the convention framing, they exclude “the popular will” of those who might otherwise challenge their narrative, their authority, and ultimately, their power.

Cropping the Frame of Assembly: The Democratic National Convention

“We can’t let you in.”

I stepped out of a meeting with Senator Bernie Sanders at the Chicago Teachers Union, where he was discussing labor issues faced by working-class Americans to a half-empty room. A small Democratic contingent from Wisconsin had just returned from a demonstration, still holding signs calling for a ceasefire in Palestine. Organizers with the Progressive Coalition were preventing the registered group from entering (conveniently forgetting the public call for more members to join). A police officer was called to the scene.

“It sounds like they want to have us removed,” Heba Mohammed, a member from Milwaukee, explained to me. “We intended to go in there peacefully, which shouldn’t be an arrestable offense.”33

Denied entrance, the contingent requested to speak with Senator Sanders after the event so they could pass along their petition for an arms embargo against Israel. They waited for him in the lobby but were later informed that he had left the event through the back door.

The Democratic National Convention began with protests.34 Large demonstrations calling for the Biden-Harris administration to end the genocide in Gaza and assault on Lebanon drew hundreds of protesters through the streets of Chicago, making their way to the United Center, where two rows of metal barricades marked the convention perimeter. A third row was put in place after protesters breached the first security barrier.35 Officers in riot gear lined the barricades (many of whom were brought in from jurisdictions outside Chicago36)—masks down, batons in hand. Drones hovered above, surveilling the protests and the crowd in yet another panoptic performance of power.

Writing on the tensions between law enforcement and public assembly, Butler highlights the mechanisms by which the state attempts to control public spaces in order to limit a challenge to its authority. “Demonstrations are one of the few ways that police power is overcome, especially when those assemblies become at once too large and too mobile, too condensed and too diffuse, to be contained by police power.”37 Architecture, then, becomes a tool to intensify police power, to control the size, mobility, and concentration of the people in protest. Attempting to create and hold the line between public and private, between an accepted and lawful political assembly and an unlawful, outside threat to the party’s “unified body,” the structure of the DNC’s metal fence was itself a tool for defining “the people.” It was a site for determining who was permitted to participate and who was permitted to appear. As Butler suggests, “the question of justice emerges precisely at the site of entry,” where the barricade—though temporary and mobile—operates as a bordering regime. The DNC’s physical security barrier to control access to the United Center operated in tandem with an abstract credentialing system operated by law enforcement and party organizers.

Photographers covering the protests throughout the week were required to register and credential with the Chicago Police Department or risk arrest. Typically done months in advance to allow for background checks through federal and local law enforcement systems, credentialing can be a form of deterrence—making it too difficult or risky for individual photographers, reporters, and independent media organizations to cover the protests if they fail to secure a pass ahead of time. The process also forces or curates a stream of media coverage that law enforcement can control and monitor. Surveillance is easier when everyone is identified.

Walking from the Chicago Teachers Union to the arena, I was guided by police officers through residential streets reserved for those with layers of colored passes. Cut off from their own neighborhood, residents sat on their stoops, watching as we followed the barricaded path to the arena entrance reserved exclusively for media and guests. I was able to enter the convention perimeter only after a thorough security sweep of my camera gear. Bypassing the perimeter security altogether were the state delegates and party officials, who arrived at the convention grounds by bus, private cars, and motorcade. The spatial controls meant to differentiate, exclude, and limit access to the arena establish a hierarchy of power even among the accepted assembly. This is further established spatially inside the arena—where access to different levels is granted depending on state affiliation, connection to party members, or proximity to the presidential candidate.

On the final day of the Democratic National Convention, the sidewalk at the entrance to the United Center became the site for a 24-hour sit-in led by the Uncommitted Movement of Democratic delegates—mirroring the hundreds of student-led encampments that occupied college campuses throughout the US in the spring of 2024. Abbas Alawieh, a member from Michigan and cofounder of the Uncommitted Movement, had spent the week prior canvassing other delegates to help send a message to the Harris campaign that, unless the Biden-Harris administration committed to an immediate ceasefire in Gaza and an arms embargo on Israel, significant swaths of the party base would not vote for her come the November elections.38 At the start of the convention, the uncommitted delegates numbered 30, representing some 700,000 primary voters across the country.39 And yet their canvassing did not gain enough delegate support to sway the party’s performance inside the arena. “We ran out of options on the inside, so we are standing here on the outside,” said Alawieh.40

Outside the United Center—or “at the site of entry,” to stay with Butler—members of the uncommitted movement contested the party’s conditions of assembly, fielding media questions and making phone calls to party organizers, pushing for a Palestinian American to speak on the DNC stage. Party officials, delegates, and guests were forced to see and hear the calls to end the US-backed Israeli genocide in Gaza. Their appearance—one that has largely been cropped out of the official convention framing—ruptures the image of a unified body the Democratic Party has worked to maintain through “the regulation of the public space,” refusing to become an instrument of the party’s “theatrical self-constitution.”41

Inside the arena, a long procession of speakers took the stage, which included notable progressives, high-profile Republicans, Border Patrol agents, union leaders, Hollywood celebrities, and working-class Americans—all responding to the convention theme: “For the People, for Our Future.” The event showcased a coalition of diverse voices, claiming an inclusive and universal “right to appear,”42 but stopped short at Arab Americans, who were left outside, unable to enter or participate.43 In the final hours of the convention, the uncommitted movement was denied their request for a Palestinian American speaker, none of their other demands met. For the Democratic Party, “the people” is qualitative and “our future” is conditional, a vision of utopia that is, drawing on Ursula K. Le Guin, “closed in upon itself.”44

While restricting participation within the physical enclosure of the arena, the party expanded its reach to the virtual public square by credentialing—for the first time—more than 200 content creators with an estimated audience of more than 350 million viewers across various social media platforms.45 For the DNC, these creators were an opportunity to “loosen the script” and influence people “not just through their content, but through their unique ability to speak authentically to their own communities.”46 The party’s labeling of influencers as “authentic” community members must be understood alongside its denial of many of their own party members’ authenticity and their ability to speak or represent the needs of their communities. In addition, the emphasis on “authenticity”—on “unscripted” content—conceals the reality that these individuals are regulated by the same spatial conditioning as traditional media in the context of the convention. Chaperoned by party officials throughout the week, creators had exclusive access to party officials, private lounges, catered luncheons, and sponsored events,47 and to a creators’ platform on the convention floor where they could make their videos.

As I made my way over to the platform where a group of creators were standing—taking selfies and posting video updates—I recognized a Democratic operative from the Obama White House. She warned me they were about to go live. In just a few minutes, the arena lights went up and a television crew began to film. Deja Foxx, a social media influencer from Tucson, Arizona, with more than 140,000 TikTok followers and 52,000 Instagram followers—as well as a former Harris campaign staffer48—took the mic to share her personal journey. With the other creators standing behind her in a show of support, Foxx ended her speech with a call to action for youth voters: “It’s a fight for our future. We have a responsibility to do this and we have a responsibility to do it right. And that is why we show up for Kamala Harris and Tim Walz.”49 The arena cheered.

Harris’s digital strategist, Rob Flaherty, insisted that the campaign was not replacing traditional media for content creators, stating, “We certainly don’t expect any of those creators who are here to be propagandists for Kamala Harris and Tim Walz.”50 Yet their actions say otherwise. With a large number of media floor passes now allocated to creators, I found my own mobility limited in terms of where I could move and how much time I could spend on the convention floor. Spaces normally reserved for the press were offered to creators. And since Harris was announced as Biden’s replacement, the number of photographers traveling with her was cut from six to one,51 and sit-down interviews with Harris during the DNC were offered exclusively to content creators, including Vidya Gopalan, a North Carolina mom with 3.4 million TikTok followers.52

This pivot is especially true for the Republican Party, which has put a concerted effort into developing a new right-wing media ecosystem53—of content creators, podcasters, YouTube stars, and alt-news organizations—to discredit legacy media and drown out dissenting voices, seeing access to information not as a constitutional right but as a privilege.54 Paradoxically, both parties still rely on a mediator to disseminate their narrative, though instead of relying on traditional media to do so, they now rely on tech companies, whose bottom line is profit. The virtual “public square” the Democratic Party worked to access during the convention is conditioned by algorithms that decide who will be seen and what will be said based on ad revenue potential. Ironically, these algorithms are managed by billionaires who ultimately supported Trump. The boundaries of the virtual space of participation are policed in exactly the same manner as the physical space, creating yet another space of power-making.

Countering Within the Party Frame

“And together, let us write the next great chapter in the most extraordinary story ever told.”

I am photographing Harris onstage with her family as she says these final words. One hundred thousand balloons drop from the rafters into the buffer zone where I am standing, building a wall so high, I can no longer see. I turn and focus my lens on the delegates seated behind me, joyously playing with the falling balloons, none of which were gold—a fact emphasized (underlined in bold) in an email sent out earlier that day by the DNC.55

Red, white, blue, gold: The color makes no difference to me. I am photographing in black and white, stripping away the tribal aesthetics of the two parties, leveling both conventions. These images—messy, blurred, and slightly out of focus—clash with the clean, sharp, and well-lit scenes that heighten the orchestrated performances. For me, photographing on the convention floor at eye level creates a form of “ground-truthing,” a process used by aerial image and remote sensing interpreters “to measure and compare the ground elements with the elements that compose the image.”56 By “anchoring” the panoptic perspective with a perspective at ground level—where convention goers can see me and I them, where we can be in communication with one another—I aim to individuate the attendees: to work against the party’s narrative of “the masses.”

I widen my focus from the stage to its material surroundings—the rafters holding the balloons, the rope managing the crowd, the signs waving for Harris, the cables transmitting images, the keffiyehs breaking the sea of American flags—disclosing the physical assemblage that shapes the space and enables the party’s operation. Staying until the end, I photograph the workers tasked with cleaning up the confetti, collecting the chairs, and popping the balloons, creating images that reveal the often hidden and unacknowledged roles that maintain the party’s vast infrastructure, the continuous wheel of the political machine.

Navigating these spaces of power-making, I am concerned with finding methods for counterframing from within: bringing in what has intentionally been left out; centering narratives of marginalized voices; using the aesthetics of black-and-white imagery to disassociate the colors of tribal politics; turning away from the planned event to focus instead on the larger infrastructure at work; and creating a dialogue between disparate images composed of diptychs and triptychs made at different moments in time and space.

Butler argues that any photograph or series of images that constitute “the people” “would function as a potentially exclusionary designation, including what it captures by establishing a zone of the uncapturable”—those absent or outside or shut out from the camera’s purview. I would argue that photography has the potential to counter the party’s spatial organization of power precisely because it is included and/or emerges from within the contours of this power—it can work within and against to contest, for example, “the distinction between the public and the private,”57 between the home, the street, and the arena. Considering, instead, that the relation between images opens up the space for the democratic struggle to take place, broadening the body politic and creating a more expansive designation of “the people.”

Here, I am reminded of Leviathan, a seventeenth-century work by the political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, in which he laid the groundwork for social contract theory and Western political thought.58 Hobbes opens his influential work with an etched black-and-white triptych illustrating the creature Leviathan, wearing a crown and carrying a scepter, overlooking his empire. A closer look reveals that the Leviathan is composed of many individuals, coming together from different places, creating a larger body politic in the image of this one sovereign ruler.

The American people came together in November to elect Trump for a second term in office. However, the Trump administration is no longer concerned with continuing the narrative of popular sovereignty to legitimize its authority. Rather, it is intent on creating a “parallel information universe” where memes, AI-generated imagery, and social media posts “reframe the narrative,” attacking dissent and aggressively drowning out any opposing messages, especially from the news media.59 Forcing its own revisionist narrative, the administration self-legitimates Trump’s authority and reaffirms his image as sovereign—as evidenced by the White House’s social media post of an AI-generated image of Trump as king60—while cropping out the popular will.

Photographers, therefore, are uniquely positioned to counter the party’s narrative framing and push against these spaces of power-making, practicing a politics of refusal against the regime’s media apparatus. Photographs can champion another narrative, one that does not serve an exclusive elite or reify the party, but reminds the body politic that like the people coming together to support the Leviathan, so too can they walk away and dismantle it, taking its power back with them.

-

Abbas Shirmohammadi has been photographing national political events since 1985, when he established his photography studio, Panoramic Visions. ↩

-

Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 85. ↩

-

Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, 85. ↩

-

Jill Lepore, “How to Steal Elections: The Crazy History of Nominating Conventions,” The New Yorker, June 27, 2016, link. ↩

-

These sports arenas are spatially representative of ancient stadia, where crowds gathered to watch the spectacle of athletic tournaments. Statesmen and politicians were known to take advantage of the “concentration of people to impress and to influence them,” making the stadia “important places for the representation of power.” Bettina Kratzmüller, “Ancient Stadia, Politics and Society,” in Stadium Worlds: Football, Space and the Built Environment, ed. Sybille Frank and Silke Steets (New York: Routledge, 2010), 37. ↩

-

Sybille Frank and Silke Steets, “The Stadium—Lens and Refuge,” in Frank and Steets, Stadium Worlds, 282. ↩

-

Rather than the orchestrated “joy” pushed by Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign. Alyssa Oursler, “A Campaign of Joy Alongside the Horrors of Genocide,” The Nation, August 21, 2024, link. ↩

-

Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, 19. ↩

-

His ear was nicked and did not require stitches. ↩

-

Allowing the gathered spectators to “perceive each other physically and visually.” Frank and Steets, “The Stadium—Lens and Refuge,” 282. ↩

-

Riser positions are guaranteed to wire services and media organizations with large readerships. Smaller organizations will be placed in the risers depending on the number of available positions left. ↩

-

I was on the Standing Committee of the Gallery as the elected freelance representative from 2018 to 2020. My role was to act as a liaison between the press and the federal government, advocating for media access at the US Capitol, though I was also tasked with assisting in preparations for the 2020 US National Conventions, which were ultimately scaled back due to the Covid-19 pandemic. ↩

-

Frank and Steets, “The Stadium—Lens and Refuge,” 282. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977), 359. ↩

-

Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 358. ↩

-

Maurice Berger, “Social Studies,” in James Casebere: Model Culture, Photographs, 1975–1996, ed. Andy Grundberg (San Francisco: Friends of Photography, 1996), 13. ↩

-

Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, 164. ↩

-

Frank and Steets, “The Stadium—Lens and Refuge,” 290. ↩

-

Frank and Steets, “The Stadium—Lens and Refuge,” 290. ↩

-

Stephen Collinson, “GOP Sees Divine Intervention in Trump’s Triumphant Return,” CNN, July 16, 2024, link. ↩

-

Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 337. ↩

-

The “pool” refers to a small group of press photographers who are given exclusive access to the candidates when space is limited, traveling with them to document “official government business.” While the aim is to photograph unscripted moments that may offer the public better insight into the campaign’s inner workings, the campaign will often carefully stage these moments. What the public does not see are the dozens of Secret Service agents and campaign staff who direct photographers to their designated positions at every event, whether backstage to project an image of intimacy and relatability, behind the speaker to depict the masses gathered for the candidate, or in the “well” of the rally—the space between the front row and the stage—to create larger-than-life images of the candidates. ↩

-

Kara Milstein, “Behind the Cover: Interview with the Photographer of the Trump Image,” Time, July 15, 2024, link. ↩

-

Frank and Steets, “The Stadium—Lens and Refuge,” 293. ↩

-

For example, a narrative that says: Just as Jesus died on the cross to save our souls, so too did Trump take on a bullet to save us, save democracy, save America. A narrative that, according to the New Apostolic Reform movement, believes that God is working through modern-day apostles. Stephanie McCrummen, “The Army of God Comes Out of the Shadows,” The New Yorker, January 9, 2025, link. ↩

-

Fahmy credits the popularity of her business to their local production, claiming “all 50,000 people [at the convention] are strong believers of ‘made in America’ and really promoting America.” Marin Rosen, “RNC Convention Fest Draws Attention to Local Milwaukee Businesses,” Daily Cardinal, July 16, 2024, link. ↩

-

Ariana Baio, “RNC Booth Hosts AR-15 Giveaway, Days After Trump Assassination Attempt,” Independent, July 17, 2024, link. ↩

-

Both parties sell merchandise and hire vendors for the week of the conventions. The Democratic Party had theirs off-site, outside the convention complex, with only a few gift shops within the convention arena offering official DNC merchandise. ↩

-

Shawn Michelle Smith, At the Edge of Sight: Photography and the Unseen (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), 14. ↩

-

The Democratic Party runs similar events during its own national conventions. ↩

-

Recorded by the author, July 17, 2024. ↩

-

Jonathan Swan, Shane Goldmacher, and Maggie Haberman, “How Trump Dominated His Own Party on a New G.O.P. Platform,” New York Times, July 18, 2024, link. ↩

-

Heba Mohammed, conversation with the author, August 19, 2024. ↩

-

The RNC in Milwaukee had fewer protests; however, it is important to mention a significant demonstration that erupted after the killing of Samuel Sharpe Jr., a Black unhoused man, by five police officers who were brought in from Columbus, Ohio, specifically for the RNC, raising significant questions about the jurisdictional legality of out-of-state police and the disruption to the local community by their presence. “Our Milwaukee police officers know about this camp and know about the people staging there and understand the issues that go along with experiencing homelessness,” said Shelly Sarasin of Street Angels, an outreach group that provides materials for unhoused people staying at the tent encampment. “He didn’t have to be shot… by an officer who wasn’t from here.” John Diedrich, Ashley Luthern, Jessica Van Egeren, Sophie Carson, Bethany Bruner, Bailey Gallion, Shahid Meighan, David Clarey, Michael Loria, and Michael Collins, “Fatal Shooting of Homeless Man Raises Security Questions About Out-of-State Police at RNC,” USA Today, July 16, 2024, link. ↩

-

Faith E. Pinho and Jenny Jarvie, “Small Group of Protesters Breach Barrier at DNC Protest in Chicago,” Los Angeles Times, August 19, 2024, link. ↩

-

Sophia Tareen, “Chicago Police Chief Says Out-of-Town Police Won’t Be Posted in City Neighborhoods During DNC,” Associated Press, July 25, 2024, link. ↩

-

Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, 74. ↩

-

Vice President Harris would eventually lose Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, key swing states with large Arab communities. Representative Rashida Tlaib, the only Palestinian American in Congress, won reelection in her Detroit district. ↩

-

Joseph Stepansky, “‘Uncommitted’ Delegates Bring Gaza-War Message to Democratic Convention,” Al-Jazeera, August 17, 2024, link. ↩

-

Uncommitted National Movement, Twitter, August 22, 2024, link. ↩

-

Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, 85. ↩

-

Judith Butler reminds us that “no matter how ‘universal’ the right to appear claims to be, its universalism is undercut by differential forms of power that qualify who can and cannot appear.” Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, 50. ↩

-

The fire marshal shut down the arena’s floor access hours before Vice President Harris was to speak, claiming the arena had already reached capacity. ↩

-

In her novel The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Le Guin explores the limitations of utopian societies that push ideologies that are often stifling, rigid, and self-referential rather than open to change and external influence. ↩

-

Almost three times the number, compared to the RNC. Elena Moore, “From Lost Followers to Backlash in the Comments, Content Creators Reflect on the DNC,” NPR, September 1, 2024, link. ↩

-

John Wihbey, quoted in Tanner Stenning, “Social Media Invasion: Content Creators Flood the DNC. Speaking Roster Includes Five Influencers,” Northeastern Global News, August 20, 2024, link. ↩

-

Ken Bensinger, “Free Booze, a Lake Cruise, and Selfies Galore: How Democrats Courted Influencers at the D.N.C,” New York Times, August 23, 2024, link. ↩

-

Sarah D. Wire and Rachel Barber, “Harris Campaign’s Embrace of Social Media Influencers Is Years in the Making,” USA Today, August 21, 2024, link. ↩

-

Elena Moore, “Gen Z Activist Deja Foxx Is the First Content Creator to Speak at the Convention,” NPR, August 20, 2024, link. ↩

-

Stephanie Kelly, “At DNC, Influencers Battle Journalists for Space and Access,” Reuters, August 21, 2024, link. ↩

-

Traditionally, the campaign will accommodate an extended photography pool of six photographers. The Harris campaign cut that number down to just one photographer, citing increased security. The White House News Photographers Association (WHNPA), a 105-year-old member organization of visual journalists based in the Washington, DC, region, sent a letter to the Harris campaign urging them to increase the number of photography positions. The White House News Photographers Association, September 2024, link. ↩

-

Betsy Klein, “Influencers Get Prime DNC Access as Part of Harris’s Campaign Strategy,” CNN, August 22, 2024, link. ↩

-

Kayla Gogarty, “The Right Dominates the Online Media Ecosystem, Seeping into Sports, Comedy, and Other Supposedly Nonpolitical Spaces,” Media Matters, March 14, 2025, link. ↩

-

David Bauder, “The [Trump] White House Has Argued That Press Access to the President Is a Privilege, Not a Right, That It Should Control—Much Like It Decides to Whom Trump Gives One-on-One Interviews,” ABC News, April 16, 2025, link. ↩

-

The balloons at Trump’s Republican National Convention included gold ones. “The balloon drop features assorted red, white, and blue balloons, both standard size 9” balloons and 24” balloons. There are no gold balloons in the Democratic National Convention balloon drop.” Emily Soong, Press Secretary, Democratic National Convention Committee, email, August 22, 2024. ↩

-

Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (New York: Verso, 2021), 125. ↩

-

Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, 71. ↩

-

An actual or hypothetical contract or agreement between the ruled or between the ruled and their rulers, where an individual’s rights are transferred to the sovereign thereby authorizing their power over the individual for the greater society. ↩

-

Drew Harwell and Sarah Ellison, “Inside the White House’s New Media Strategy to Promote Trump as ‘KING,’” Washington Post, March 6, 2026, link. ↩

Gabriella Demczuk is a Lebanese-American photographer, spatial researcher and educator, focused on the issues of political ecology, the proprietary modes of abstraction, and counter narratives. She spent ten years working as a member of the White House press, photographing three presidential administrations, Washington politics, and stories across the US related to immigration and environmental policy for various publications including the New York Times, TIME, and the Washington Post. She is co-founder of Al-Wah’at, an artist-research collective committed to developing spatial, community, and ecological practices of care and repair, centered on arid lands and futures. Gabriella teaches Media Studies in the School of Architecture at the Royal College of Art and holds a graduate degree from the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London.