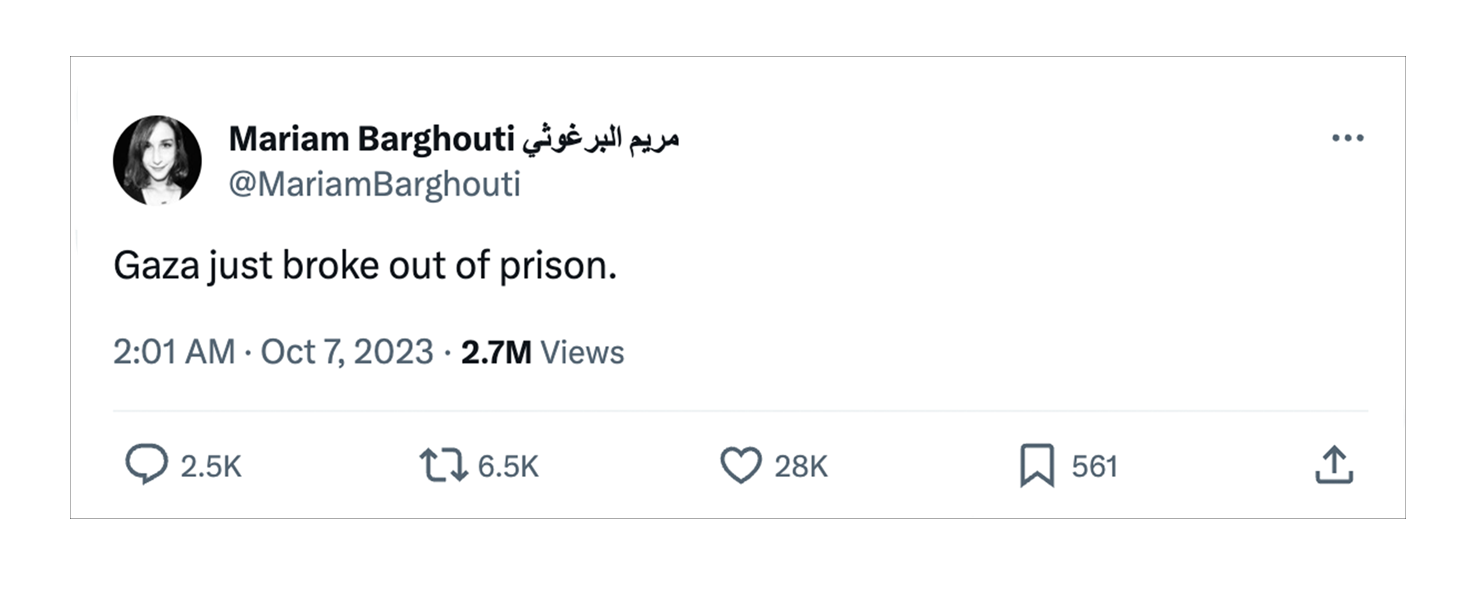

When my four-and-a-half-year-old wakes up each morning, a new day of running, chasing, reasoning, bargaining, giggling, and meltdown aversion begins. In those early moments of getting going, I squeeze in as lengthy a scroll through the headlines as possible; on Saturday, October 7, 2023, my bleary eyes read a tweet by journalist Mariam Barghouti several dozen times: Gaza just broke out of prison.

This, before any correlated images, continuing context, and certainly before any flurry of think pieces.

The initial shock of the statement carried my mind to the Gilboa Prison break of September 6, 2021, when six Palestinian prisoners—Zakaria Zubeidi, Mahmoud Abdullah Ardah, Mohammed Qassem Ardah, Yaqoub Mahmoud Qadri, Ayham Nayef Kamamji, and Monadel Yacoub Nafe’at—escaped through an underground tunnel in the prison’s drainage system, which they dug with spoons, plates, and pan handles. The six men were all recaptured within two weeks, but their mark made on the infinite pathways to freedom endures in our collective imagination, building upon generations of resistance, and on the more recent Unity Intifada.1

The break, the rupture, the escape of October 7 also conjured the feather weight of freedom. Before the subsequent worlds-altering salvo filled my feeds, as documented by journalists like Motaz Azaiza, Hind Khoudary, Wael al-Dahdouh, Moamen Al Sharafi, Mohammed Zaanoun, Belal Khaled, and Plestia Alaqad—tirelessly speaking truth to occupation with their words, images, existence—my mind flashed to the singular minuscule stone that tumbled ahead of an avalanche of heaving earth: a portion of the apartheid wall in al-Ram, Jerusalem, that collapsed in February 2022.2 Sporadically, segments of the sinuous cement partition will cave—typically due to seasonal floods—only to be hastily replaced.

As Shahram Khosravi stresses, we live in a time of wall fetishism: the project of colonial accumulation by dispossession and expulsion that steals wealth, labor, and time.3 Borders take, extract, encroach. They diminish, constrict, and obstruct the temporal and sensorial. Materials and machinery are tested for their life-sucking precision on those pillaged of agency, though never perfected, for the sake of the next development contract for “improvement.” While that section of the wall in al-Ram has since been rebuilt, and the voracity of colonial conquest across al-Quds continues to mount, the wall’s crumbling reassures us of these structures’ material limits, their temporariness—affirming the human and more-than-human rejection of all borders.

Here, perhaps, I should elaborate on Israel’s retaliation on Gaza—and throughout occupied Palestine—that ensued almost immediately after this October’s break. Aerial bombardment across the besieged coastal enclave has flattened hospitals, mosques, schools, gasoline and water reserves, farms and agricultural prowess,4 theaters, archives, universities, churches, bakeries, homes, news bureaus, legacies and livelihoods, entire family lineages. Mothers clutching their torched babies’ corpses, shrieking into our phone screens to end the atrocity, the catastrophe, again. I can’t put numbers here—to the dead and displaced souls, to the buildings toppled, to the scorched earth; any digit as a placeholder is already incorrect as I think through the next sentence. The barrage, at time of publishing, has not ceased—for seventy-five days. For sixteen years.5 For seventy-five years. For 106 years. Fady Joudah reminds us: “each land has its people / each time has its folks and time / for a while now has been standing on our throats.”6

The notion of broke(n), here, contains infinitudes. And I do not dare consider speaking to/of the shattering of lifeworlds that Gazans, and all Palestinians from the river to the sea and across diasporas, have and continue to experience—throughout this war, and all the versions of conquest and pillage they and the land have endured.7

I know for certain, though, that the versions and visions of freedom that Palestinians are showing the world—of breaking out of Zionist settler colonial framings and fearmongering, of imperial domination and plunder—are ones we should study closest and amplify loudest.8 Tareq Baconi insists we focus on how Al-Qassam Brigades:

[Reveal] the strategic poverty at the heart of the assumption that Palestinians would acquiesce indefinitely to their imprisonment and subjugation. More importantly, [Al-Aqsa Flood] laid waste to the very viability of Israel’s partitionist approach: the belief that Palestinians can be siphoned off into Bantustans while the colonizing state continues to enjoy peace and security—and even expands its diplomatic and economic relations in the wider region.9

My fixation on the rupture of the Gaza border, and connecting with borderlands everywhere,10 is to venerate the possibility of a less-bordered world. Everyone’s attention and subsequent reflections as October 7 (and beyond) unfolded fixates on death and destruction wrought by both sides. Perhaps this piece can ask us to consider that the demolition of that wall was actually a physical, visceral action of creation.

Maybe that’s not easy for us all to see. Or maybe just not right now, amid the unending horrors we scroll through. But this creation of new worlds, where we are millions and billions increasingly, collectively, demanding a dismantling of the war machine, is in motion. For some, those demands are made peacefully—and for others, the resistance is by any means necessary. I am not one to judge nor prescribe the/a solution, of course. But my aim is to connect the dots between these borderlands, and beyond.

And so, despite the urgency of the ongoing horrors in Gaza—across Palestine—I offer a pause,11 on possibility—of uprising against and the dismantling of borders. Karim Kattan knows settler colonial conquest is as much about space as it is about time:

The wall speaks to our imagination: concrete that shrouds the sky and towers over the human beings treated like cattle underneath. It is a convenient placeholder for the magnitude of apartheid and colonization. Yet, the workings of the Israeli machine are not usually monumental. The wall is an aspect of Israeli power—and not necessarily the most important one. Indeed, one of its most brilliant achievements is that it is self-effacing, even unassertive in day-to-day life. It is a silent conquest stretching over moments and decades.12

If we consider borders as a consolidation—of power, prowess, profit—materially, spiritually, ecologically, existentially laying ruin to land and its stewards… so too can we consider them a physical and psychological delimitation of the settler colonial imagination.13 So too can we claim power in the pause; extoll the breaking of borders.

We need to remember: they hang glided over the damn wall.

An image so spectacular and sublime, so surreal that I’d imagine its impossibility and implications were nearly immediately squashed in our psyches by the onslaught of the occupier’s assault. I’ll assume that, in some ways, I’ve internalized the border-military-industrial complex’s capacity for stifling and siphoning a future-oriented world—and the ways that it’s wrecked and reordered the pastpresent.14 Meaning: Who among us considers the efficacy of a flitting and flimsy nylon parachute against trillion-dollar walls and machinery?15 A Free Palestine does.

There were brief flashes of the resistance hang gliders circulating on social media; cartoons and silhouettes of the bodies suspended weightlessly by the breeze, slogans of solidarity, singing praises of bravery and potential. For some, historic posters and anecdotes resurfaced, recalling the “Night of the Gliders” on November 25, 1987, when Khaled Akar and Melod Najah, associated with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine—General Command, took flight from southern Lebanon, hang gliding into occupied Palestine, catching the Israeli Northern Command and the Nahal Brigade off-guard.

Absorbed in playtime and snacks for several hours that October morning, away from any developing stories, my mind repeated ad nauseam: they just… went over the wall.

In my nearly 20 years as a Sonoran Desert dweller, I’ve only known walling—bordering—as an additive process. One that is incomprehensibly opaque. Taller, thicker, fiercer versions of fencing continue to reinforce the international boundary between the United States and Mexico, layered with surveillance towers, ground sensors, drones, helicopters, ATVs, and so much more—in the service of violating treaties and tribal sovereignty, constitutional rights, and ecological preservation for the sake of settler colonial spoil.

Here in Tucson, Arizona—unceded Tohono O’odham land—I am approximately 70 miles from the US–Mexico border wall. In June 2022, the US Border Patrol launched an observation blimp in Nogales, intended to add another layer to its matrix of persistent surveillance.16 Area residents and local officials were blindsided; US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) provided zero public notice nor addressed any community stakeholders for consultation prior to its deployment. The 22-meter-long aerostat, filled with helium and tethered to a 7.5-ton mooring platform, was staged on a privately owned hilltop above the Circle K gas station on the Patagonia Highway.

Not unlike the mechanics and methodologies of the Israeli surveillance state that Eyal Weizman elucidates in Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation, CBP’s blimps glaringly demonstrate a politics of verticality, where the borders of settler colonial structure are materialized and manifest across different topographical latitudes. In Gaza and throughout the West Bank, as across the Sonoran Desert—bastardized as the US–Mexico borderlands—the airspace, ground, and subsoil are weaponized for the perversions of those in power.17

The blimp’s liftoff caused a mild stir across this portion of the borderlands—likely because of the arrogance with which it was inserted into the landscape. It was an ostentatious eyesore that forced us all to remember—if only fleetingly—the networks and nodes of draconian border policing throughout the region. Local media coverage riled public outcry, and by January 2023, the blimp was covertly removed with nary a trace.18 During the short span of the low-altitude surveillance craft’s duty, I frequently thought, Blimps. Just hovering up over the border wall. Like this is some Super Bowl arena of detection and death-making.

With its removal, so too the greater community’s conscious awareness of 24/7 surveillance and detectability. Headlines with images of the border wall and conversations about CBP’s abuses of power vanished almost overnight. Those in Tucson and in towns closer to the international divide, like Arivaca and Patagonia, largely sank back into a routine of apathetic arrhythmia, despite the ever-present monstrosity of the wall, and other blimps’ activities.19 Perhaps surprising to many, though, is that the federal government has used aerostatic surveillance balloons across the southwest border since 2013, and the technology dates to the early 1980s, when the US Customs Service initiated a network of blimps to bolster the so-called War on Drugs.20 The second-ever aerostat network site was built at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, in 1983. In 1991–1992, the responsibility of the network was transferred to the US Department of Defense; since 2003, more than sixty-six Persistent Threat Detection System (PTDS) aerostats have been put into action in both Afghanistan and Iraq—overseeing convoys in transit while gleaning intelligence. In fiscal year 2014, US CBP assumed responsibility for the Tethered Aerostat Radar System (TARS) project, the 420K Aerostat System fleet configured across the US–Mexico borderlands.

The 420K TARS is manufactured by Lockheed Martin, one of the world’s largest defense contractors, with half its annual sales to the US Department of Defense. From an October 2020 blurb on its website, the company sentimentalizes:

From afar, it looked like a scene straight out of an H. G. Wells novel. In 2003, a series of blimp-shaped air vehicles began rising, one after another, over the arid terrain of Afghanistan.

The unusual-looking ships—helium-filled aircraft called aerostats—rose to an altitude of 15,000 feet and floated quietly in the sky, each secured to a ground-based mooring system by long tethers.

Insurgents on the ground were perplexed by what they saw. The airships didn’t seem to move, nor did they fire missiles or release bombs.

It was only when insurgents began to notice coalition forces anticipating some of their covert operations that they realized those alien-looking airships had been watching—and recording—their every movement via a new surveillance program called the Persistent Threat Detection System (PTDS).21

The “threats” are categorized as “persistent,” because if there was a functional solution, whatever that was across the spectrum of policy, it would not be in the interest of Lockheed Martin and other insatiable “defense” corporations. There would no longer be demand for divisive, destructive new Research & Development; there would no longer be a demand for “defense.” On October 7, 2023, Lockheed Martin’s AGM-114 Hellfire missiles, eagerly supplied to the Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) by the United States, were unleashed on Gaza. While Lockheed Martin’s PR team unabashedly plays to the imperial imaginary—recounting the panoptic, supranatural capture over Afghanistan—a throughline worth underscoring is how Forever War—rearing its hydra’s head through genocidal logics across Gaza and the West Bank22—is developed, tested, honed, and celebrated in the Sonoran Desert.

If this most recent reign of terror currently being brought down on Palestinians and their land has shown those of us in the United States anything, apart from their sumud in the face of seemingly insurmountable horrors,23 it is that there is no such thing as “democracy” here.24 Millions are protesting, petitioning, boycotting, blockading, defying… in the name of cease-fire, sovereignty, self-determination, and a dismantling of the apartheid regime. Yet, all this lands on the desks of the callous, profit-driven officials purportedly “elected” into office. The US government is nothing more than a handful of defense contractors stacked in a trench coat. Because these borders are business.25 Big business. The border is a billionaire.

A 2019 report co-authored by journalist Todd Miller, “No Más Muertes,” and the Transnational Institute emphasizes fourteen companies that dominate the border security business: Accenture, Boeing, Elbit, FLIR Systems, G4S, General Atomics, General Dynamics, IBM, L3 Technologies, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, BAE, Raytheon, and UNISYS, among several other top firms.26 Tracking defense contracts is a dizzying (nauseating) ordeal,27 but a brief survey of recent contracts awarded by the Department of Defense (September 12, 2023) can provide a sliver of light on the rapacity:

Lockheed Martin Corp., Fort Worth, Texas, was awarded an $841,490,130 firm-fixed-price, cost-plus-incentive-fee modification (P00003) to a previously awarded indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract (N0001923D0010)…

Lockheed Martin Corp., Grand Prairie, Texas, was awarded an Other Transaction Authority agreement with a ceiling of $311,979,039 for Stinger missile upgrades and replacement…

Northrop Grumman Systems Corp., Bethpage, New York, was awarded a $46,705,533 cost-plus-fixed-fee modification to previously awarded contract N00024-17-C-6311 for Littoral Combat Ship Mission Module engineering and sustainment support. This modification includes options which, if exercised, would bring the cumulative value of this modification to $161,210,500.28

These multinational corporations brazenly steal billions, but the wool is pulled over our eyes as this border-military-industrial-complex is rooted in and thrives off the everyday: the seemingly banal spaces of classrooms, administrative buildings, and strip malls in cities like Tucson, where these clusters of “innovation” are concentrated on the University of Arizona campus, the UA Tech Park, along the Interstate 10 corridor, and adjacent to Davis Monthan Air Force Base. “The Old Pueblo,” as Tucson is cheekily coined by gentrifiers, UNESCO-boosters,29 and myriad incarnations of settler colonial schemata alike, is the little-known hotbed of transnational fortressing and death-making manufacture.

The University of Arizona is part of the Borders, Trade, and Immigration consortium, which includes the University of North Carolina, Rutgers, and the University of Minnesota and hosts Centers of Excellence (COEs) for Research & Development, funded by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). COEs undertake research projects for the DHS and other federal agencies, raking in millions for the schools. One such project included aerospace mechanical engineering students studying locust wings, for the development of miniature surveillance drones—“Micro Air Vehicles.”30 The University of Arizona bears down on this collusion with (b)ordering the curricula in the “National Center for Border Security and Immigration” (aka BORDERS), part of the Eller College of Management.

BORDERS touts its design-science research approach to “solve real-world problems” that “respond to DHS identified interest areas and contribute to the public good.” The three “research areas” are: detection, identification and screening; sensor networks and communication; and immigration policy and enforcement.31 The software, demos, and prototypes for these research areas include automated screening kiosks, AVATAR kiosks, biometric cameras for remote surveillance and identification, checkpoint simulations, eye trackers, and the StrikeCOM multiplayer online strategy game. In 2019, the University of Arizona launched a nonprofit corporation, University of Arizona Applied Research Corp., to meet federal demands for security, defense, and intelligence projects. Austin Yamada, president and CEO of the corporation, stated, “We will work with defense, security and intelligence community sponsors to conduct the kind of research that will satisfy the cost, schedule and performance metrics that drive the federal government procurement process… Our nation faces many threats to national security that require the best and brightest minds to help develop solutions to existing as well as emerging problems, and many of the best minds in the country are at the UA.”32

While there’s much to expand upon regarding the nuance of these technologies and their detrimental impact on the safety of migrants, asylum seekers, and Sonoran Desert crossers alike, it’s worth noting that one such “community sponsor”—and by “community,” let’s call it a global aerospace and defense goliath—is Raytheon, the world’s largest producer of guided missiles.

Raytheon Missiles & Defense (RMD) is headquartered in Tucson—boasting a broad portfolio of precision weapons, radars, command and control systems, and air and missile defense systems. According to RMD’s own sources, “it has deployed border ‘solutions’ in more than 24 countries across Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia and the Americas, covering more than 10,000 kilometers of land and maritime borders.”33 The company is Tucson’s biggest employer (more than 13,000 workers run the main manufacturing campus near the Tucson International Airport) and contributes more than $2.6 billion to the Arizona economy.34 It’s no exaggeration to say the company, in tandem with the University of Arizona, is the lifeblood of the city—or, perhaps more apt, rapacious vampires sucking life from the city. In a November 2019 Arizona Public Media interview, Raytheon president Wes Kremer discussed Raytheon’s economic and spatial growth across this desert, including some of its recruitment tactics:

Host: In Tucson, the company’s outreach can begin as early as elementary school. Do you have a hard time convincing students that they want to come to a missile company, and not to an internet company or something like that?

Kremer: So you know, we’re not for everybody. [laughing]

I mean that’s reality. What we do is, we do national defense. And we tend to see that the employees that come here and stay here for a career (um) usually are very patriotic in nature, often have some connection to the military, you know—an aunt, an uncle, a father, a mother, something like that.35

One person’s, one people’s, one corporation’s defense is another’s offense. Raytheon pursues youth in the greater Tucson community, funneling them into the Research & Development pipeline, which manufactures missiles that target Palestinian children and wipe entire families off the Palestinian civil registry. Since October 7, 2023: 19,667 murdered Gazans (and climbing… an incomprehensible undercount when we consider the ongoing media and communications blackouts, kidnappings, mass graves, in addition to those yet to be recovered from the destruction), more than 10,000 of them children.36 Over 300 Palestinians, including 63 children, murdered throughout the West Bank (as of December 14, 2023). Call it what it is: the Israeli Occupation Forces.37

Raytheon produces the Tomahawk cruise missile, the Standard Missile-3 series of ballistic missile interceptors, and the AMRAAM and Sidewinder air-combat missiles in Tucson. While these weapons are currently and relentlessly ransacking Gaza, Raytheon’s hand in the destruction of Palestine and its people, and its complicity with the Israeli regime, extends far beyond the present:

As reported by AFSC Investigate, Raytheon provides Israel with missiles compatible with Israeli F-16 fighter jets, including the AGM Maverick air-to-surface missile, the TOW missile, and the AIM-9X Sidewinder. Raytheon also produces missiles which Israel uses to arm its fleet of F-35A aircraft. Israel spends a significant portion of the billions in USD of military “aid” that the US provides it each year on Raytheon weaponry. In 2015, for example, Raytheon sold 250 AIM-120 AMRAAM missiles to Israel for $1.8 billion through US foreign military sales.

Israel has used Raytheon’s missiles and bombs repeatedly in its attacks on densely populated areas in Palestine. In 2008–2009, Israel used F-16 aircraft armed with Raytheon missiles in its aerial assault on Gaza (so-called “Operation Cast Lead”), in which Israel killed 1,383 Palestinians and injured 5,300. Following this murderous aerial bombing campaign, Amnesty International found fragments of a 500-lb bomb with Raytheon markings amongst the rubble in Gaza. The Israeli military used F-16 fighter jets armed with Raytheon missiles in its 2014 aerial assault on Gaza (so-called “Operation Protective Edge”). The Israeli Navy uses Raytheon Phalanx weapon systems to enforce its ongoing naval blockade of the Gaza Strip, through which Israel deprives Gaza’s [more than] 2 million residents of materials necessary for constructing and maintaining basic humanitarian and civilian infrastructure (such as water purification and functioning sewage systems).38

In August 2020, it was announced that Raytheon Missiles & Defense partnered with Haifa-based defense company Rafael to expedite joint US production for Iron Dome.39 The flow of so-called counterterrorism training, weapons, and surveillance equipment from Israel is far from limited to exchange with the US. Seizing on the present rise of fascist regimes and emboldened colonial expansionism, Israel is capturing the market; in 2022 it exported a record $12.556 billion in defense equipment and surveillance.40 The “Database of Israeli Military and Security Export” (DIMSE) map estimates that Israel exports military equipment and arms to around 130 countries worldwide.41

But aiding and abetting the IOF has become the US’s unique brand—from Cop City42 to the Deadly Exchange;43 lying and gaslighting by pseudo-progressive politicians;44 from the scores of wars on Gaza and beyond in years past; from Obama’s $38 billion package to Trump’s slashing of aid to Palestine… to the additional billions of taxpayer dollars specifically for Iron Dome development in recent years.

Israel is unabashedly a world leader in the design and implementation of security imperialism and is invigorated by bellicose partisans and adjacent profiteers. With consistent congressional backing, Israel models and exports a sweeping surveillance state. P.L. 116-283, the William M. (Mac) Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2021, contains Section 1273 of the United States Israel Security Assistance Authorization Act of 2020, which “authorizes ‘not less than’ $3.3 billion in annual FMF [Foreign Military Financing] to Israel through 2028 per the terms of the Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs)…”45 and ostensibly guarantees at least $38 billion in military aid to Israel. This perennial financial and ideological endorsement all but guarantees Israel’s aggressive expansion of weapons and surveillance technology worldwide, the Zionist settler colonial imperative extended farther and deeper into every terrain of the globe. This impetus for societal and territorial domination signals the next phase of what Catherine Besteman terms “militarized global apartheid” (2019):

The new apartheid apparatus takes the form of militarized border technologies and personnel, interdictions at sea, biometric tracking of the mobile, detention centers, holding facilities, and the criminalization of mobility… It stretches across most of the globe, depends on an immense investment of capital, and feeds a new global security-industrial complex. Because the new apartheid relies on and nurtures xenophobic ideologies and racialized worldviews, it recasts the terms of sovereignty, citizenship, community, belonging, justice, refuge, and civil rights and requires the few who benefit to collectively and knowingly demonize and ostracize the many who are harmed.46

The louder the drumbeat for more border funding here, the more missiles we ship over there, and vice versa.47 In an October 24, 2023, earnings call,

Greg Hayes, the CEO of RTX [Raytheon], delivered an earnings report to investors on Tuesday. He eagerly notified them that increased US funding for Israel will generate fresh contracts for missiles from the company’s Raytheon division. “Across the entire Raytheon portfolio, you’re going to see a benefit of this restocking,” he told shareholders. Kristine Liwag, a Wall Street analyst for Morgan Stanley who was on the call, said the war against Palestine appeared to be an “opportunity” that “fits quite nicely” with the company’s product offerings. Hayes agreed. He characterized Israel’s war as a bonus over and above already-expected U.S. military expenditures. The extra orders for Netanyahu’s IDF, he said, come “on top of what we think is going to be an increase in DOD [US Department of Defense]” funding.48

The more brutal the offensive on Gaza and across historic Palestine, the bigger the boost for shareholders. A grotesquely delayed cease-fire, which ultimately would return us to the untenable status quo of prolonged occupation and apartheid—unless we demand its abolition—means record profits for warmongers. The border is a billionaire.

And then I recall: they plowed through the wall.

A last bedfellow of Tucson’s border-military-industrial complex that I’ll mention here, despite the options being plentiful, is Caterpillar, Inc. Headquartered in Irving, Texas, the American™ construction, mining, and engineering manufacturer brags of over sixty primary locations in twenty-five states; “Caterpillar is a part of the United States infrastructure.”49 2019 saw the completion of Caterpillar’s $58 million, 150,000-square-foot building in the heart of downtown Tucson, along the Santa Cruz River. Local council people and Rio Nuevo development hawks lauded the arrival of the company’s new regional headquarters.50

It is impossible to separate Caterpillar’s presence from flagrant extraction, dispossession, displacement, and desecration on every continent; its mustard-yellow machinery perched on open pit mines… clawing at pipeline routes… boring and blasting for the next NIMBY block. Around Tucson and throughout this desert, Caterpillar equipment cuts/carves/splices through Tohono O’odham and Pascua Yaqui lands in the interest of Sonoran sprawl and the latest iteration of The Border. A cogitation: In the O’odham language, there is no word for wall.51

A lesser-known subsidiary of the company is Caterpillar Defense Products, which develops combat engineering vehicles as well as components for infantry fighting vehicles used by the Finnish, Swedish, Danish, and Swiss armies, among others. Caterpillar equipment in the service of the IOF includes illegal settlement construction, the razing of Palestinian and Bedouin homes and property, the construction of the Separation (Apartheid) Wall, the creation of roadblocks and checkpoints across all of Palestine, and for dispersing anti-occupation demonstrations. As early as 2004, Human Rights Watch urged Caterpillar to suspend bulldozer sales to the Israeli military; its “Razing Rafah” report detailed the systematic abuse of the machinery, frequently employed to demolish thousands of homes in Gaza.52 The Caterpillar D-9 armored bulldozer dominated the IOF’s “Operation Defensive Shield” during the Second Intifada.53 The Who Profits research center details:

The most famous heavy engineering machine used by the Israeli army is the Caterpillar D9 armored bulldozer. D9s were extensively used in the Israeli attacks on Gaza in 2008–2009 and in 2014, and for operational tasks such as large-scale house demolitions in Gaza, land-clearing missions in Palestinian towns and arresting or killing Palestinian suspects using the “pressure cooker” procedure. The “Pressure Cooker” procedure is an Israeli military practice used to pressure a person wanted on a charge of terrorism who fortifies in a house, to come out. In such cases, Israeli military Combat Engineering Corps demolish the structure with the person still inside, even in the case of that person being killed in the process. This procedure has been used against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza. This procedure is performed with Caterpillar excavators models Caterpillar D9 (L/N/R/T), Caterpillar 966 (E/F/G/H), Caterpillar 330, and Caterpillar 349.54

During those few frames from October 7 now etched into our brains—the grapple bucket bursting through steel bollards and layers of concertina wire—the bulldozer forceful and fast through the fencing by Abu Khammash (ابو خماش), clan of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe lands, or so-called Kisufim55… “CATERPILLAR” was displayed across the windshield.

While Audre Lorde instills in us that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house, this death-making equipment can still be a small part of the toolkit to reaffirm life; we’ll soar over it. We’ll plow through it. We’ll tunnel under it. We’ll blockade what builds more of it. This is the presentfuture of all walls.

Millions have taken to the streets since October 7—from Balochistan to Copenhagen, São Paulo to San Francisco and beyond—to decry Israel’s genocidal warfare against Palestine. We are belting the urgent demand for permanent cease-fire… the Palestinian right to self-determination and sovereignty… calling to end US taxpayer funding of Israel’s apartheid regime. A seismic shift in public consciousness is rumbling among us; we’re coming out in droves to oppose carte blanche funding and manufacture for the US war machine and all its abuses—demanding the dismantling of its Zionist settler colonial bedfellow.56 Here, I want to uplift the imperatives from the Palestinian Youth Movement’s “The First Week” communique:

The foremost demand to anyone inside the West, inside the imperial core, is to oppose the genocidal drumbeat waged by Zionist and Western leaders alike. The Palestinian people of Gaza have asked for the bombing campaign to stop, the blockade to end once and for all, and for humanitarian aid to enter. But also and more broadly, what we are asking those who wish to be in solidarity within the West is threefold. First, struggle through organizations and your workplaces and your communities and in the streets to demand an end to both the current genocidal campaign and for an end to the entire system of settler colonialism that has strangled Palestine for the last century. Second, go on the offensive: demand sanctions against Zionism; no more weapons, no more money, no more cultural or institutional cover. We want the total anti-normalization of a Zionism that has once again shown its face to the world. Finally, understand Palestinian resistance as fundamentally just and as a means of survival for our people; it will not stop in the weeks and months to come, and you must be prepared not to waver again.57

Many of us came of age during the Second Intifada and all the perversion of the War on Terror sprung forth from 9/11: a confluence of insecurity, fear(war)mongering, xenophobia, anti-Blackness, anti-Indigeneity… I guess anti-everything, except austerity and unfettered capitalism that stymied our potential before we started to know ourselves. No matter where you’re reading this, you’ve known nothing but War—with varied degrees of privilege that define our relations and proximities to gore. But the bulldozer and hang gliders, those on foot stepping into their land, gifted us all the visuality of a viable borderless present, future. It’s upheaval—a heaving of earth and walls and caging—that certainly did not begin on October 7, nor were the ruptures instants of finitude. Rather, this fracturing of Zionist settler colonial time and space—of borders and ordering—alerts us we’re very much in the throes of profound change. Fargo Nissim Tbakhi writes:

The long middle is not a condition of time; we might be nearer to the end of revolution than the beginning, we might be nearer liberation than defeat, but our experience and our actions exist within the frame we can see, the frame of the long middle. Liberation is the end, but it is a geographical end rather than a temporal one, a soil and not an hour. We move towards it—sometimes slowly, sometimes quickly, but always. It is the location by which we orient our movement. We know it because it gets closer, not necessarily because it comes sooner.

(And liberation moves too, it has its own sort of agency, it can dance a little, as you stare through the hole in the fence you’ve just cut you might feel a hand on your shoulder, someone standing by your side like a friend, liberation letting you know what it feels like, that you’re going the right way.)58

From this middle, the only way is forward. This moment in Gaza and across Palestine—and all these ways of seeing/liking/reposting/creating/co-conspiring, documenting, and disrupting—is our chance to define anti-imperialism, anticolonialism, and the dismantling of Forever War—on our terms.

-

In Arabic, “intifada” translates as rebellion, uprising, resistance movement. Across Palestine and the diaspora, intifada is an invocation of strength and courage in the face of oppression. The First Intifada (1987–1993) and the Second Intifada (2000–2005) provided frameworks, lessons, and visions for the Unity Intifada (2021–present). Al-Shabaka policy analyst Yara Hawari synthesizes: “The ongoing Palestinian uprising against the Israeli settler-colonial regime in colonized Palestine did not begin in Sheikh Jarrah, the Palestinian neighborhood of Jerusalem whose residents face imminent ethnic cleansing. While the threat of the expulsion of these eight families certainly catalyzed this mass popular mobilization, the ongoing uprising is ultimately an articulation of a shared Palestinian struggle in the wake of over seven decades of Zionist settler-colonialism. These decades have been characterized by continuous forced displacement, land theft, incarceration, economic subjugation, and the brutalization of Palestinian bodies. Palestinians have also been subjected to a deliberate process of fragmentation, not simply geographically—into ghettoes, Bantustans, and refugee camps—but also socially and politically. Yet the unity witnessed over the last two months as Palestinians across colonized Palestine and beyond mobilized in shared struggle with Sheikh Jarrah has challenged this fragmentation, to the surprise of both the Israeli regime and the Palestinian political leadership alike. Indeed, popular mobilization on this scale had not been seen for decades, not even during the Trump administration, which oversaw the recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, the normalization agreements between Israel and various Arab states, and the further acceleration of Zionist settler-colonial practices. Beyond mobilizing on the streets, Palestinians have been using creative forms of resistance against their subjugation. This includes the revitalization of grassroots campaigns to save Palestinian neighborhoods in Jerusalem from destruction and ethnic cleansing, the disruption of the Israeli regime’s economy, and the continuous engagement of a globalized world with clear messages demanding freedom and justice for Palestinians.” Yara Hawari, “Defying Fragmentation and the Significance of Unity: A New Palestinian Uprising,” Al-Shabaka, June 29, 2021, link. ↩

-

This spectacular moment circulated briefly during the week of February 4, 2022, when this section of the wall collapsed, following heavy rainfall, due to an accumulation of rubble against it. Al-Ram is northeast of occupied Jerusalem, near the Qalandiya refugee camp and the Neve Ya’akov Zionist settlement. As documented by B’Tselem since 2016, the wall surrounding al-Ram—and its calamitous correlated technologies—severely hampers Palestinians’ access to schools, hospitals and medical clinics, and the movement of labor and merchandise, and severs community continuity; see B’Tselem, “The Separation Barrier Surround a-Ram,” January 1, 2016, link. To view the clip of the wall falling, see link. ↩

-

Shahram Khosravi, “What Do We See If We Look at the Border from the Other Side?” Social Anthropology 27, no. 3 (2019): 409–424. ↩

-

For more on the IOF’s practice of herbicidal warfare against Gaza, see Shourideh Molavi, Environmental Warfare in Gaza: Colonial Violence and New Landscapes of Resistance (London: Pluto Press, 2024); Forensic Architecture’s 2019 investigation “Herbicidal Warfare in Gaza,” link; B’Tselem, “Military Sprays Herbicides along Gaza Border, Destroying Crops in 200 Hectares,” March 9, 2017, link. For more on my use of the term “IOF” when referring to the Israeli military, see footnote 37 in this essay. ↩

-

None of this began with October 7, 2023. It is our responsibility to situate this moment in Gaza, and Palestine more broadly, within the long durée of settler colonial history and its interminable violences. For more on the siege of Gaza and various forms of resistance within and beyond the region, see The Dig, “Hamas with Tareq Baconi” (podcast), link; Jadaliyya’s “Gaza in Context,” link; and the scholarship of Rashid Khalidi, Noura Erakat, Diana Buttu, Maya Mikdashi, and scores more. ↩

-

Excerpted from Fady Joudah, “Tell Life,” Poetry (November 2013), link; to be accompanied with Fady Joudah’s “A Palestinian Meditation in a Time of Annihilation: Thirteen Maqams for an Afterlife,” Literary Hub, November 1, 2023, link. ↩

-

There is no possible way to describe the totality of horror the Israeli occupation of Palestine inflicts upon the land and its people—nor is it my story to tell. But in the interest of building our resources for learning/sharing/advocating/collaborating, some of my recommendations for better understanding this geopolitical moment include: Salman Abu Sitta, The Atlas of Palestine (1917–1966) (London: Palestine Land Society, 2011); Ahmad Sa’di and Lila Abu-Lughod, eds., Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007); Noura Erakat, Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019); Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017 (New York: Macmillan, 2020); as well as projects by Palestine Open Maps, Zochrot, Visualizing Palestine, Forensic Architecture, Akevot, 7amleh, and many others who archive atrocity—and co-create roadmaps for freedom. ↩

-

We are witnessing—participating in—actions… in paradigm shifts of speed and scale not yet wholly grasped. Some of the loudest gestures include blockading ZIM cargo vessels… trade unions and dockworkers disrupting global arms shipments, temporarily shutting down bridges, highways, consulates, and conventions, and demanding accountability for public servants at all levels of government. However, it’s important to remember that solidarity and resistance occur out of the public eye, too. Educators, artists, writers, caregivers, and the world’s nurturers are building spaces for safety… for knowledge production, and for defying the unsound status quo. We can think of community organizing and the role of women during the First Intifada (1987–1992), when radical educational mobilization and redistributed domestic labor sustained the popular uprising. For more, see E. S. Kuttab, “Palestinian Women in the ‘Intifada’: Fighting on Two Fronts,” Arab Studies Quarterly 15, no. 2 (Spring 1993): 69–85, link; Naila and the Uprising, directed by Julia Bacha (produced by Rula Salameh and Rebekah Wingert-Jabi, Just Vision, 2017). ↩

-

From Baconi’s commentary for Al-Shabaka. See Tareq Baconi, “An Inevitable Rupture: Al-Aqsa Flood and the End of Partition,” Al-Shabaka, November 26, 2023, link. See also Tareq Baconi, Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018). ↩

-

This is deeply informed by Nick Estes, Melanie Yazzie, Jennifer Nez Denetdale, and David Correia’s discussion of the “bordertown” in Red Nation Rising: From Bordertown Violence to Native Liberation (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2021): “The bordertown most commonly describes the cities and towns along recognized international borders, such as the US-Mexico border. These are considered the borders that matter in the everyday life of a settler. We draw on Native vernacular, an everyday language of resistance, to recognize the borders that settlers ignore. These borders exist everywhere settler order confronts Native order. And since we find this confrontation everywhere in settler society, everything in a settler world is a border, and every settler is haunted by this border—a Native presence that should not exist, that blurs the edges of settler ontology” (6). ↩

-

Not the insulting “humanitarian” kind of pause. A chance for us to sit with ourselves. With community we have, and that we are continuing to cultivate. ↩

-

Karim Kattan, “Imagining Palestinian Futures Beyond Colonial Monumentality,” The Funambulist 37 (August 2021), link. ↩

-

For a useful, albeit hideously tragic overview of the ecological devastation in Gaza, see Sonikka Loganathan, “In Gaza, Israel Is Waging an Invisible Environmental War,” The Hindu, November 27, 2023, link. ↩

-

Nick Estes, Melanie Yazzie, and others in Red Nation Rising write: “We must remind ourselves that borders on this hemisphere are recent lines drawn by the claws of capitalism. Borders preserve an imbalance, favoring those who benefit from the misery of broken kinship. Capitalism’s insatiable hunger for violence is manifested by every border structure it builds. The suffering and indignity Palestinian people experience when crossing an Israeli checkpoint is similar to that of Yaqui people held at gunpoint by US border patrol agents, with the same company providing walls and surveillance technology for both borders” (x). ↩

-

For a crucial account of the Israeli military industry, see Ali H. Musleh, “Designing in Real-Time: An Introduction to Weapons Design in the Settler-Colonial Present of Palestine,” Design and Culture 10, no. 1 (January 2018): 33–54. ↩

-

Here, as in much of my research, I’m indebted to the labor of Caitlin Blanchfield and Nina Valerie Kolowratnik in “‘Persistent Surveillance’: Militarized Infrastructure on the Tohono O’odham Nation,” Avery Review 40, May 2019, link, and other countercartographies of the Sonoran Desert that help me view my home in indispensable new light. ↩

-

There are over 20,000 ground sensors, part of the webs of technology for the “virtual” wall, across the US–Mexico border. For more, see Erica Hallerstein, “Between the US and Mexico, a Corridor of Surveillance Becomes Lethal,” Coda, July 14, 2021, link. ↩

-

P. Ingram, “Grijalva Urges ‘Transparency’ from CBP after Surveillance Blimp Is Lofted over Nogales,” Tucson Sentinel, July 6, 2022, link. ↩

-

Other CBP TARS operational in the US southwest are deployed in Yuma and Fort Huachuca, Arizona; Deming, New Mexico; and Marfa, Eagle Pass, and Rio Grande City, Texas. ↩

-

“CBP’s Eyes in the Sky,” US Customs and Border Protection, April 11, 2016, link. ↩

-

“Sentinels of the Sky: The Persistent Threat Detection System,” Lockheed Martin, link. ↩

-

While the entirety of the West Bank is under attack, at a range of scales, urgent attention must turn to Masafer Yatta and Jenin. See Ramzy Baroud, “The Ethnic Cleansing of Masafer Yatta: Israel’s new Annexation Strategy in Palestine,” Mondoweiss, June 2, 2022, link; and Mariam Barghouti, “A Nakba Is Unfolding in the Occupied West Bank, Too,” Al Jazeera, November 29, 2023, link. ↩

-

We celebrate sumud (steadfastness), but we cannot overlook the exhaustion (depletion) of remaining on, remaining dedicated to, the land. In an Instagram post on November 26, 2023, Mariam Barghouti quoted Gazan journalist Mohammed Mhawish: “We are wallahy just too much exhausted of being called anything like strong and resilient and steadfast. We are too tired of this hell. Five wars for me a twenty four year old is just too enough. Tired of living it, of anticipating, of surviving, of going through it again and again and again.” For an elaboration on the term, see also Rana Issa, “Nakba, Sumud, Intifada: A Personal Lexicon of Palestinian Loss and Resistance,” The Funambulist 50 (October 2023), link. ↩

-

From the Palestinian Youth Movement’s dispatch in December 2023: “What is clear is that the Western imperial powers desperately want you to believe that this collective punishment is justified; they want you to hate the Palestinian, from fighter to infant, so that you turn away and shrug.” See Palestinian Youth Movement, “Two Months,” New Inquiry, December 8, 2023, link. ↩

-

Decades of US foreign policy aiding and abetting the Israeli regime—including the December 8, 2023 United Nations Security Council veto, December 11, 2023's United Nations General Assembly “against” vote, and the Biden administration's insistence on unconditional billions in aid/weapons for the Netanayhu administration—are demonstrative of the US Government's belligerence towards ambitions of global security and peace. For more: Creede Newtown, “A History of the US Blocking UN Resolutions Against Israel,” Al Jazeera, May 19, 2021, link. ↩

-

For comprehensive analyses of defense contractors and related stakeholders’ involvement/reproduction of the US–Mexico border wall and correlated bordering, see Geoffrey A. Boyce, “The Rugged Border: Surveillance, Policing and the Dynamic Materiality of the US–Mexico Frontier,” Environment and Planning D, Society & Space 34, no. 2 (2016): 245–262; Todd Miller, Empire of Borders: The Expansion of the US Border around the World (New York: Verso, 2019); and Felicity Amaya Schaeffer, Unsettled Borders: The Militarized Science of Surveillance on Sacred Indigenous Land (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022). ↩

-

“As of October 2023, the United States has 599 active Foreign Military Sales (FMS) cases, valued at $23.8 billion, with Israel. FMS cases notified to Congress are listed link; priority initiatives include: F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Aircraft; CH-53K Heavy Lift Helicopters; KC-46A Aerial Refueling Tankers; and precision-guided munitions.” See “US Security Cooperation with Israel: Fact Sheet,” Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, US Department of State, October 19, 2023, link. ↩

-

See “Contracts for Sept. 12, 2023,” US Department of Defense, link. ↩

-

Todd Miller, “Follow the Money: The University of Arizona’s Border War,” NACLA, March 22, 2012, link. ↩

-

“BORDERS Research,” National Center for Border Security and Immigration, Eller College of Management, University of Arizona, link. ↩

-

Pam Scott, “New UA-Affiliated Corporation Targets Defense Research,” University of Arizona News, February 5, 2019, link. ↩

-

Todd Miller, More Than a Wall: Corporate Profiteering and the Militarization of US Borders (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute, 2019), link, 32. ↩

-

“Raytheon’s Economic Impact to Arizona Now Tops $2.6 Billion,” press release, October 2, 2019, link. ↩

-

AZPM, “Raytheon Missile Systems President Discusses Growth and Priorities in Tucson,” YouTube, November 22, 2019, 4:23, link. ↩

-

“Over 10,000 Infants and Children Killed in Israel’s Gaza Genocide, Hundreds of Whom Are Trapped Beneath Debris,” Euro Med Human Rights Monitor, December 9, 2023, link. ↩

-

Here, amplifying the efforts of groups like Al-Haq and Forensic Architecture, whose human rights monitoring, legal analysis, and reporting explicitly utilizes “IOF.” A 2012 analysis by legal scholar Noura Erakat explicates Occupation Law and Israel’s attempts to legitimate self-defense amid its ongoing occupation of Palestine, reposted in Noura Erakat, “No, Israel Does Not Have the Right to Self-Defense in International Law against Occupied Palestinian Territory,” Jadaliyya, July 11, 2014, link. ↩

-

From the Mapping Project’s integral undertaking of “[developing] a deeper understanding of local institutional support for the colonization of Palestine and harms that we see as linked, such as policing, US imperialism, and displacement/ethnic cleansing. Our work is grounded in the realization that oppressors share tactics and institutions—and that our liberation struggles are connected. We wanted to visualize these connections in order to see where our struggles intersect and to strategically grow our local organizing capacities.” See “Raytheon,” Mapping Project, link. ↩

-

For an introduction as to why Iron Dome is integral to Israel’s siege on Gaza, see Dylan Saba, “Iron Dome Is Not a Defensive System,” Jewish Currents, May 25, 2023, link; and Khaled Elgindy, “No, Iron Dome Doesn’t Save Palestinian Lives,” Middle East Institute, September 24, 2021, link. ↩

-

MEE Staff, “Arab States Purchased Nearly a Quarter of Israel’s Record 12.5bn in Arms Exports,” Middle East Eye, June 13, 2023, link. ↩

-

See the Database of Israeli Military and Security Export, link. ↩

-

This reciprocal relationship between US law enforcement and Israel’s police and military has gained tremendous traction over the last twenty years. In a 2018 report by RAIA and Jewish Voice for Peace, in the months following the events of September 11, 2001: “American law enforcement representatives attended their first official training expedition to Israel to exchange ‘best practices,’ knowledge, and expertise in counterterrorism. This delegation included chiefs and deputy chiefs of police departments in California, Texas, Maryland, Florida, and New York, agents from the FBI, the CIA, and future officers of ICE, and directors of security at the MTA in New York City. Participants were schooled in Israeli military approaches to intelligence gathering, border security, checkpoints, and coordination with the media, and met with high-ranking officials in the Israeli police and military, the Shin Bet, and the Ministry of Defense. Since then, US law enforcement exchange programs with Israel have become standard, with hundreds of American law enforcement officials from across the country going to Israel for trainings, and thousands more participating in security conferences and workshops with Israeli personnel in the United States.” It is through this deadly exchange that militarized logics of security and surveillance are normalized, and historically marginalized communities and social movements are increasingly violently repressed amid rampant police abuses of power. ↩

-

Anthony Apodaca and Kellie Kuenzle, “Bernie Sanders Is Failing This Moment,” Mondoweiss, December 4, 2023, link; Ellie Quinlan Houghtaling, “Here Are All the Democrats Who Voted for the ‘Anti-Zionism Is Antisemitism’ Bill,” New Republic, December 5, 2023, link. ↩

-

Catherine Besteman, “Militarized Global Apartheid,” Current Anthropology 60, no. 19 (2019): S27. ↩

-

See “FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Supplemental Funding Request,” Department of Homeland Security, October 20, 2023, link. ↩

-

C. J. Atkins, “US Weapons Makers Tell Investors to Expect Big Profits from Israel’s War,” People’s World, October 27, 2023, link. ↩

-

For more on Rio Nuevo, gentrification, and racialized dispossession in Tucson, see Sarah Launius and Geoffrey A. Boyce, “More Than Metaphor: Settler Colonialism, Frontier Logic, and the Continuities of Racialized Dispossession in a Southwest US City,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111, no. 1 (2021): 157–174. ↩

-

Tohono O’odham Nation, “The Tohono O’odham Nation Opposes a ‘Border Wall,’” YouTube, February 18, 2017, link. ↩

-

“Israel: Caterpillar Should Suspend Bulldozer Sales,” Human Rights Watch, October 28, 2004, link. ↩

-

For more, see Stephen Graham, “Lessons in Urbicide,” New Left Review 19, no. 19 (2003): 63–77; and Eyal Weizman, Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability (New York: Zone Books, 2017). ↩

-

From the Institute of Palestine Studies’ “Real Names of Stolen Villages, Illegal Settlements of the Gaza Perimeter,” see link. ↩

-

Mass movements in Arizona against warmongering corporations like Raytheon, Elbit Systems, Leonardo, and Caterpillar since October 7, 2023 were initially slow-moving, but joyously, they are gaining traction despite Tucson Police Department, Arizona Board of Regents, and University of Arizona president Robert Robbins’s intimidation tactics. On November 30, 2023, actionists successfully blockaded the UA Tech Park (where Raytheon is located), leading to a very temporary closure. It wasn’t without scandal, however, as Senior Field Correspondent for KJZZ Fronteras Desk (and local NPR affiliate) Alisa Reznick was arrested while reporting. Actionists are building local coalitions to demand a “genocide-free economy.” John Washington, “KJZZ Reporter Covering a Pro-Palestinian Protest among Group Arrested by Pima County Sheriff’s Deputies,” AZ Luminaria, November 30, 2023, link. ↩

-

Palestinian Youth Movement, “The First Week,” New Inquiry, October 14, 2023, link. ↩

-

Fargo Nissim Tbakhi, “Notes on Craft: Writing in the Hour of Genocide,” Protean Mag, December 8, 2023, link. ↩

Taylor Miller is a researcher and photographer based in Tucson, Arizona. She earned her PhD in Geography from the University of Arizona. Her creative practices enmesh psychogeography and vernacular mapping—with interest in connecting the Sonoran Desert with global flows, ruptures, and blockages of the imperial war machine. She's motivated by border abolition and cactus propagation.