Braving a rainy afternoon in New York City this past June, I went to see The Absolute Restoration of All Things, an exhibition by artist Miguel Fernández de Castro and anthropologist Natalia Mendoza at Storefront for Art and Architecture. Since its founding in 1982, Storefront has been at the forefront of endeavors to reshape the way public spaces are understood and admired, a mission then pursued, this time, by a display of artifacts that provide a counter-imaginary to prevailing conceptions of the desert.1

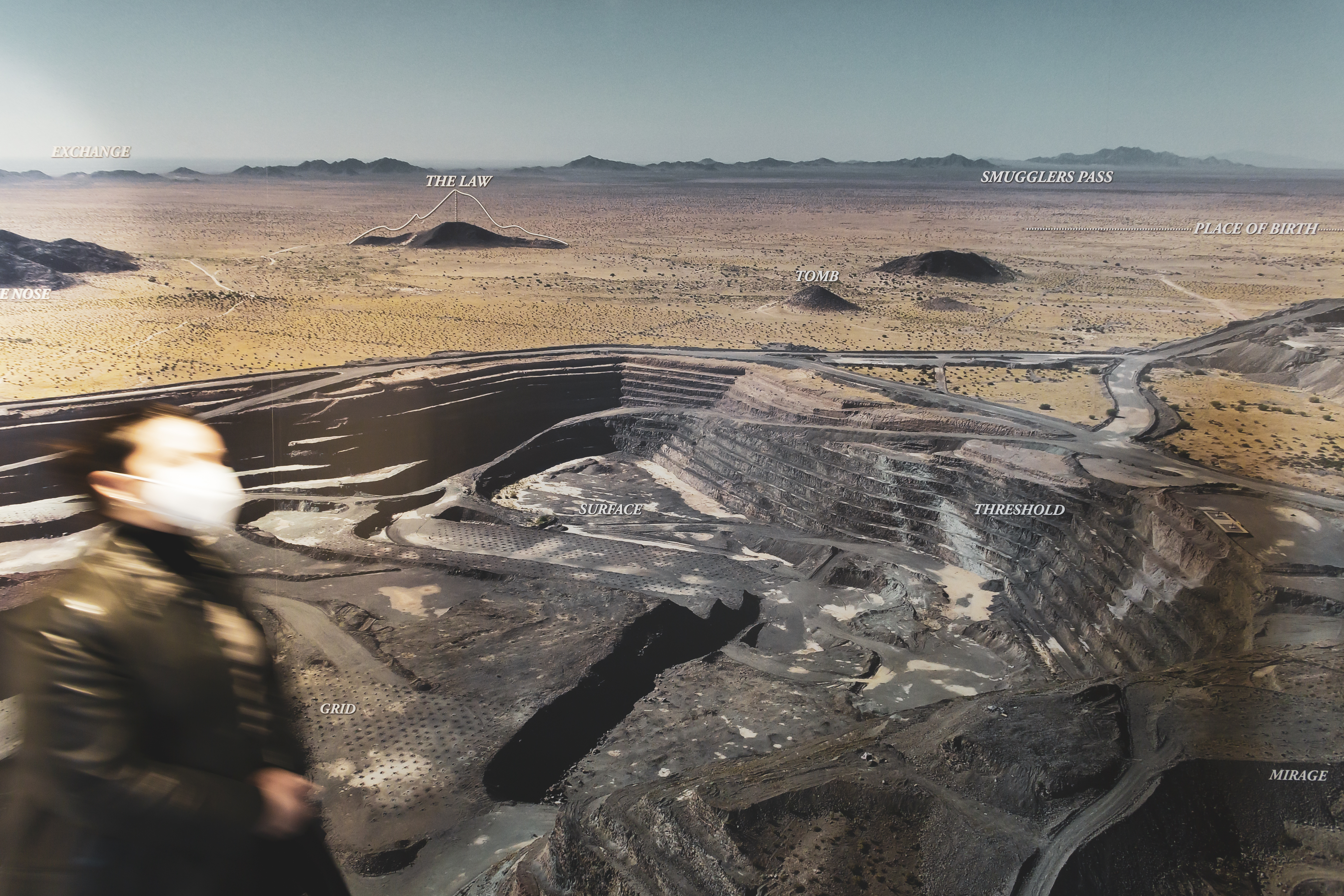

The Absolute Restoration of All Things offered an interdisciplinary and multimedia approach to the Sonoran Desert as a way to rethink established attitudes vis-à-vis built and unbuilt environments, as well as urbanized and non-urbanized spaces. Objects on display could be touched and consulted, including a mill rock once used to crush gold-rich stones, an artisanal sieve, a deer skull collected from the desert, and a wooden mold used in the production of a sculpture that, though located elsewhere, was central to the exhibition. Several wall-sized diagrams, graphs, and aerial photographs captured layers of law, Indigeneity, expropriation, and restoration. A continuously running video presented a history of extractive exploration in this part of Mexico, providing a haunting context for the transformative impact it has had on both people and their environment. Using varied media to narrate a story set in the Sonoran Desert, The Absolute Restoration of All Things ultimately pushed back against Saharanism—a universalizing desert imaginary—to depict deserts for what they are: places where people have long lived, created, and procreated, but which are being disfigured by exploration and capitalistic extraction, altering their environments forever.2

The Absolute Restoration of All Things recentered deserts, which for centuries have been marginalized and imagined as spaces of racialized exploitation, most recently manifested in their transformation around the world into testing grounds for nuclear weapons, “greening” projects, zones of detention and death, and containers for ecological disaster. Today, deserts may evoke images of narcotraffickers, smugglers, undocumented migrants, and terrorist militias. Whether along the US-Mexico border or in the Sahara, these imaginaries override the deep connections that have always existed between deserts, their inhabitants, and their adjoining vital spheres.3 The association of deserts with this criminalizing imaginary has served as a justification for myriad policing, gridding, securitizing, and extractive projects that continue to violently remake them across the world.

Especially since the 1994 launch of Operation Gatekeeper, the United States has transformed the Sonoran Desert into a macabre panopticon where hyperadvanced technologies such as drones, infrared cameras, ground sensors, and electrified fences monitor and regulate human mobility.4 The recent expansion of a wall between the United States and Mexico, in particular, exposes the Sonoran as a space where geopolitical power is leveraged through technologies of separation, detention, and incarceration, despite having accommodated boundless mobility for centuries. Likewise, the flow of sub-Saharan African immigrants has led to the incorporation of the Sahara into European borders, delocalizing the European Union’s “control mechanisms and thus its border, gradually letting it slide the Mediterranean to the Sahara and its Atlantic coast.”5 Europe’s sliding into the “devoided” and “dangerous” Saharan geography has placed Africa in the heart of Europe, making extensions between the Sahara and the Mediterranean even more concrete than Fernand Braudel had ever suggested.6

Against this background of hegemonic, fearmongering desert imaginaries, The Absolute Restoration of All Things grappled with some recent, encouraging, and curious legalese. Rarely does one encounter such significant jurisprudence that sets a precedent for restorative justice in deserts like the one rendered by the 28th District’s Unitary Agrarian Court in Mexico in 2014.7 Mendoza and Fernández de Castro’s exhibit revisited this remarkable ruling against the Penmont Mining Company, which, in the three years between 2010 and 2013, illegally operated the Soledad-Dipolos open-pit mine and extracted 236,000 ounces of gold near El Bajío, a cooperatively-owned community in the northwest of the state of Sonora.8 This extracted gold “would take the shape of a 70 x 70 x 70 centimeter cube and would have a value of 436 million dollars.”9 This gold cube required a massive enterprise that included digging up and moving 10,833,527 tons of rock. The resolution of a lawsuit originally filed by four community members, this milestone court ruling has dramatic ramifications for the conceptualization of the desert at the intersection of judicial thinking and Indigenous understanding of land rights and ecological care.10 This radical decision not only required the company to pay restitution for its extractions, but it also contained an impossible remedial dimension.11 Pursuant to the ruling, Penmont has the duty to “fully restore the ecosystem that prevailed in this place, with its hills, mountains, water, air, flora, and fauna that existed before.”12

The destruction of desert environments around the world has of course previously resulted in different forms of administrative sanctions, fines, and incarceration. A set of cases against Chinese administrative officials who failed to stop pollution in the Tengger Desert around the time of the Penmont case shows that retributive decisions are not unique.13 The Tengger chemical pollution cases began in 2014 and were settled through mediation in 2017, when eight polluting enterprises agreed to “pay CNY 569 million (USD $82,463,768.10) for the restoration of the contaminated soil and for the prevention of future pollution, and another CNY 6 million (USD $869,565) to a public welfare fund for environmental damage.”14 Although significant in its recognition of pollution in the desert environment, the Tengger case is far from the sweeping decision in Mexico that ordered Penmont’s restitution of the extracted gold and restoration of the ecological desert space to a state that existed prior to the company’s injurious extractive activities.15

The Unitary Agrarian Court's injunction operates under the assumption that a landscape can be restored to an original state, but Fernández de Castro and Mendoza rhetorically wonder, “To which natural state?” Demonstrating the impossibility of such an identification, the exhibition featured a large topographic representation of the El Bajío area with words like “law” and “extraction” inscribed upon hills and mountains amid the debris of the remade space. This projection of legal terminology onto topography was accompanied by a graphic that presented the sentencing as a spell, enunciating a new jurisprudence in an area that the state alone had heretofore monopolized as a source of national wealth. Law is spoken into the desert, where its words could have an effect following the total disfiguration of the murdered land, albeit one that is as yet unknown.

Open-pit extraction sites are open wounds. Companies displace colossal amounts of natural materials in their search for valuable minerals. The intensive detonation of rocks, use of poisonous chemicals like cyanide and arsenic, and clearing of mountaintops create new topographic realities that disfigure even the most familiar places. Mining disrupts geological time, and no amount of remedial funds or creative architecture will ever succeed at making whole what Penmont destroyed in its gold-seeking mission. Nonetheless, restorative initiatives have become a standard undertaking all over the world, with states and societies increasingly aware of the need to clean and repurpose decommissioned mines, particularly sites that are close to urban environments. According to Quarry Magazine, “Restoration schemes create opportunities to do something unique and interesting with an area of land, which can meet the policies set by local authorities and also create positive public interest.”16 Accordingly, beyond just eliciting architects’ and designers’ creative responses to anthropogenic damage, remediation projects are situated at the intersection of architectural innovation, landscape design, and environmental awareness. As such, the order by the 28th District’s Unitary Agrarian Court for Penmont to restitute the landscape and its ecosystem has a holistic resonance, validating community members’ right to reclaim the integrity of their desert environment.17

However, given the absence of a concrete plan for the execution of the court’s decision and Penmont’s continued retaliation against the community members who initiated the lawsuit, the exhibit reveals the gap between legal pronouncement and reality.18 A spokesperson for Fresnillo (of which Penmont is a subsidiary) declared to The Guardian that the company “has complied fully with the court order and as a result, vacated 1,824 hectares of land, resulting in the suspension of operations at Soledad-Dipolos since 2013.”19 The company’s purported compliance flies in the face of the court order, which stipulates, similarly, that Penmont has “the obligation to restore the ecosystem to the way in which it was originally found, its hills, mountains, pastures, water, and the original flora and fauna of the place.”20

The keywords here are “compliance” and “restoration,” and while the company seems to understand them in the narrowest sense possible, the crystal-clear ruling orders a God-like geological intervention to return the entire ecosystem to its “original” state. The novelty and the challenge of this historic decision lie herein: the prescriptive language of the law does not have to account for the actual human ability, or lack thereof, to reassemble the product of thousands of years of sedimentation and growth. By requiring this from Penmont nonetheless, the sweeping ruling both acts as a deterrent against future extraction and opens a breach between an impossible restoration and the validation of the community’s demands for the company to end its mining activities, cease the use of chemical contaminants, and compensate the ejidatarios (cooperative community members) for the damages caused.21

Embracing the breach, The Absolute Restoration of All Things drew on this impossibility. And this is key because, in the event it were possible, the total reparation ordered by the court would only foster environmental amnesia. Repurposing and redesigning landscapes that testify to brutal attacks on ecosystems creates a condition of possibility for forgetting the ecocides entirely. The artists adopted an opposite process, which foregrounded the extent to which the environmental space of the desert was mutilated and questioned the very possibility of making earth whole again. It was shocking to discover the egregious toll the production of $436 million worth of gold takes on nature. The short video, which looped and echoed in the gallery, submerged visitors in the trenches, the gaping quarries, and the winding roads once taken by heavy-duty trucks in their three-year unearthing of the desert. The monstrousness of the aftermath of Penmont’s open-pit mining leaves no room for amnesia, for its environmental crime against the people and their land is inscribed in “rocks much older than the dinosaurs.”22 The artists drove a wedge between the seemingly all-curing solution of the law and the amnesiac reparative projects that are expected to make a fragmented land whole again. Visitors were thrust into the ugliness of the quarries that attests to the violence done to the desert by modern machinery, pushing them to reconsider any idealistic understandings they might have had about recovering the land’s original state.

The immensity of this damage is potently reflected in an almost invisible cubical sculpture that now stands as “an anti-monument to the site’s dispossession” at the center of the Soledad-Dipolos mine.23 Conceived by the artists and built by the ejidatarios who still live on-site, the sculpture is an exact replica of the structure that would have been formed by the gold extracted there.24 Anti-monuments and counter-monuments have proliferated worldwide to undo and contest dominant narratives that govern the grammar of memory, offering alternatives to the meanings imposed by grand monuments to given events. James Young has written that a counter-monument in the very specific context of Germany “functions as a valuable ‘counter-index’ to the ways time, memory, and current history intersect at any memorial,” elaborating that counter-monuments aspire to elicit action from viewers.25 But while urban centers are full of pedestrians who may be prodded to act, how might one elicit action in the desert?

In the popular imagination, deserts are isolated by their very nature, and the difficulty of inciting action or at least a public outcry in favor of spaces whose life and environmental significance are not readily visible to ordinary people exacerbates the impact of their ecocides. The anti-monument, which Fernández de Castro and Mendoza helped build and then showcased in their exhibit, resists the possibility of forgetting about the desert population and the related pitfalls of technocratic restorative projects. It is also an anti-monument to discourses of desert emptiness, for it was community members' hands that built and shaped the cube.26 Instead of gold, the earthen memorial is made from the soil of the mining site; and instead of embracing eye-pleasing aesthetics, the sculpture stands in the middle of the monstrous quarry as a witness to extraction’s ability to cannibalize both people and their environment. Since the ruling, a dozen community activists involved in the fight against Penmont have been murdered or were disappeared; the anti-monument thus also stands as a tribute to desert Indigeneity and its “disappeared.”27

An American Saharanism

Beyond the ways the historic decision in favor of the ejidatarios informs The Absolute Restoration of All Things, the exhibit has larger historical and transregional resonances that connect the Sonoran Desert to other deserts around the globe. The imaginary underlying the extraction, legal or illegal, of desert resources against the will of their Indigenous stewards has been in place for centuries. It is the product of a racializing ideology undergirded by military might and knowledge production about desert populations. This imaginary, what I have termed “Saharanism,” entails a universalizing idea of deserts as empty and lifeless spaces, providing the conceptual justification for brutal, conscienceless, and life-threatening actions in desert environments.28 Whether the issue is the transformation of deserts into loci for the storage of nuclear waste or experimentation with sophisticated security technologies for border control,29 a long legacy, both direct and indirect, of Saharanism exists.30 Hence, Saharanism is the ideational blueprint for projects whose existence and survival require that deserts remain fearsome, threatening, and dead in the public (colonial) imagination.

The exhibition demonstrated that Saharanism pervades all desert-focused activities and cultural production and, by extension, so many other aspects of modern societies’ cultural lives. Seemingly unrelated literature (both fiction and nonfiction), enjoyable films, and even breathtaking commercials draw on Saharanist tropes to convey images of athleticism, virility, and superheroic beings who flex their might in the hostile desert space. The more one looks for Saharanism, the easier it is to see that the concept has made deserts everywhere into what they are not. They are portrayed as empty while they in fact teem with life. They are described as hostile while they have long been home to human and non-human existence. They are treated as dead while it only takes one rain shower for the desert to bloom. They are described as barren while their fertility often exceeds that of “ordinary” lands. Nevertheless, the prevalence of images of death, emptiness, and inhospitability has set the stage for deserts to be acted upon as good for nothing but extraction, in both material and nonmaterial senses. In this regard, the exhibition’s powerful message would have been even stronger had it not fully relied on mediating an experience that could have also been relayed through the voices of the ejidatarios themselves.

One could say that Fernández de Castro and Mendoza’s artwork is a de facto response to Saharanism in an American manifestation. However, while many visitors’ attention might have been captured by the powerful artifacts, photos, and video that tell El Bajío’s story, the exhibit’s engagement with the history of American Saharanism may have been too subtle to allow visitors to make this connection. The two artists strategically used quotes from American explorer Carl Lumholtz’s New Trails in Mexico (1912) to frame the video about Penmont’s illegal extractive activities in the Indigenous territories, situating it in the wake of an earlier history of American Saharanism’s approach to the Sonoran as a gold cache.31 Traveling through northwest Mexico between 1909 and 1910, Lumholtz recorded significant data about the people, fauna, and flora indigenous to the area.32 But the underlying logic of his enterprise, as can be easily surmised from the use of the word “new” in his title, was pioneership for the powerful. More concretely, gold and other minerals, more so than people and the land itself, were his main subject, attested by his conclusion that “the mineral prospects of the region, especially as regards gold, are great.” Lumholtz provides a detailed blueprint for extraction, urging American prospectors to mine “free gold” from the Indigenous Mexican desert.33

Lumholtz’s travels and ensuing book are not exceptional in any way. He is part of a long tradition of desert explorers and spiritual seekers—commissioned prospectors, adventurers, spies, geologists, military personnel, and divine prophecy followers—who shared an attraction to deserts, yet helped blaze the path discursively and practically for exploitative endeavors.34 Beyond their individual fascination with desert space, many such Saharanists also belonged to like-minded fellowships and were sponsored by societies that had a vested interest in looting deserts’ wealth, thus contributing to the institutionalization of Saharanism.35 The figure of the Saharanist has changed over time, from the prospector in the American West to that of the oil geologist in Arabia and more recently, with the increased focus on border control and security studies, now includes those who conceive strategies to police migration through deserts. The detour through Lumholtz’s explorations thus helpfully endowed the exhibition with historical resonances of extraction that Penmont’s activities alone would not have clarified.

Saharanist and Counter-Saharanist Futures

Lest readers think Saharanism is merely a Euro-American phenomenon, I hasten to add that attitudes toward deserts and their inhabitants, not geography, are what determines whether one is participating in Saharanism or not. The world has watched how petromodernity, which replaced desert climate−adapted construction with hypermodern buildings in the Arabian Peninsula, has created what novelist Abdulrahman Munif has called “Cities of Salt”: cities that have no ability to survive should the oil reserves, which are their lifeblood, reach depletion thresholds.36 In his 1984 critique of the societal and cultural transformations petroleum brought to the Arabian Desert, Munif depicts a self-devouring system in which the construction of an authoritarian polity accompanied the expropriation and displacement of the dwellers of an oil-rich desert oasis.37 Munif’s description of the traumatic uprooting and proletarianization of Wadi al-‘Uyūn’s inhabitants was a prescient rendering of the coalescence of petro-capitalism, ethnographic-like research, and power-thirsty entrepreneurs in order to lay the foundation for a despotic rule on the ruins of an erstwhile rich, albeit self-contained, desert way of life.

The ongoing development of the 10,230-square-mile Neom City in western Saudi Arabia confirms the prescience of Munif’s fictional articulation of Saharanism. A “smart city” under construction on the Red Sea, Neom boasts plans for “regreening” and “rewilding” projects in a hypermodern megapolis under the vision of its founder, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.38 The unveiling this past summer of plans to build the Line—an area within Neom that extends over 175 kilometers from the coast to the Arabian desert, with 500-meter-high buildings that will house a self-selecting population of nine million people—has been covered extensively by major media outlets.39 Supervised by Giles Pendleton, an Australian citizen, this $200 billion mega-Line in the desert “will be the largest megastructure in the world—a futuristic, mirrored residential and business block that rises over an expanse of desert, pristine, emerald waters, rocky inlets and white beaches of the rugged Tabuk province.”40 Neom is a desert city that forgets its desertness.

In Neom, all the elements of Saharanism intersect in both their local and global dimensions. The vision is grounded in and infused with sci-fi scenes produced by cinema studios elsewhere, in which a lifeless desert is populated with dreamy man-made islands even as Saudi courts are busy issuing death and heavy imprisonment sentences against its recalcitrant indigenous inhabitants.41 There is no stronger testament to Saharanism’s power than its adoption by a powerful local leader seeking to eliminate and “undesert” the ecological nature of his homeland. Saharanist extraction in Neom has its fantastical nuances. The vision here is to be shaped by human hands, hired and directed by petro-wealth to create a country of the future in a mere thirteen years. Saharanism is based on fantasy, after all, and the fascination with which Neom has been received in the international press is also fantastical, for the vision that sustains it speaks to Saharanist dreams.42

In this context, then, The Absolute Restoration of All Things contested the entrenched grammar of Saharanisms worldwide, enforced by colonial forces upon Indigenous subjects who, historically, have been silenced. This silence is of course part of Saharanism’s self-sustenance. Such is the case in the recording of nuclear “experiments” carried out by French officials in the Sahara in the 1960s, which situated the desert biome outside a chart of normal existence.43 On this matter, both jurisprudence and historiography, until very recently, have offered little. Although neither courts nor archives, colonial or postcolonial, could mitigate the harm of carrying within oneself the effects of a simulacrum of doomsday, recent projects that document the experiences of Saharan Indigenous people in their own language are finally articulating the aftermath of a deeply racialized “experimental Saharanism.”44

The Absolute Restoration of All Things shed similar light by orienting its focus on the racializing damage of desert imaginaries and drawing attention to the desert as a place full of life and conflict, where sensitive, complex understandings of the environment exist. Although the vivid urgency of the situation mediated through art and audiovisual materials could have been even livelier with more voices and faces of the people affected, the exhibit certainly succeeded in eliciting this viewer’s (and hopefully others’) indignation at the murder of an environment and its people. More broadly, the project works as a synecdoche for a centuries-old struggle between Indigeneity and Saharanism in desert areas throughout the world, intersecting with larger, increasingly visible activist and scholarly projects. As The Absolute Restoration of All Things and the articulation of Saharanisms elsewhere make clear, such ravaged deserts will never be the same.

-

The exhibition currently being shown, Public Space in a Private Time: Building Storefront for Art and Architecture, marks the gallery’s fortieth anniversary. ↩

-

The author is currently writing a book provisionally titled Saharan Imaginations: Between Saharanism and Ecocare, an intellectual history of Saharanism and its multilayered impact on desert peoples and their environments. ↩

-

I use the term “vital spheres” to refer to any place whose existence is imbricated with and shaped by deserts and vice versa. Deserts do not exist in a void. In fact, they maintain co-existential relationships with their non-desert surroundings. ↩

-

Luis Alberto Urrea, The Devil’s Highway: A True Story (New York: Back Bay Books, 2004), 19; see also Jason de Leon, The Land of Open Graves (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 155. ↩

-

Armelle Choplin, “Mauritania and the New Frontier of Europe: From Transit to Residence,” in Saharan Frontiers: Space and Mobility in Northwest Africa, eds. James McDougall and Judith Scheele (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2012), 165. Ironically, as the EU erased borders between its member states, it pressured the Saharan state of Niger to criminalize the jobs of individuals, such as drivers, merchants, and guides, who historically connected the different parts of Africa across the Sahara. Journalist Ian Urbana has reported on the infrastructures on the southern shore of the Mediterranean created by this immigration system and its border control. See Ian Urbana, “The Secretive Prisons That Keep Migrants out of Europe,” New Yorker, November 28, 2021, link. ↩

-

See Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II: Volume I (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), 171. ↩

-

This ruling was preceded by sixty-seven other court decisions whose outcomes in favor of the ejidos were not executed. The 2014 ruling, the main focus of the exhibition, draws on a precedent (188/2009) in which Penmont was defeated, and the judge used the same language of restoration. This 2009 ruling canceled the company’s permits, thus paving the way for establishing the illegality of its excavations between 2010 and 2013, which is reflected in the landmark 2014 decision. ↩

-

Javiera Martinez and Holly Jones, “The Struggle of a Community in Sonora against the Grupo Fresnillo Mining Company in Mexico,” London Mining Network, March 3, 2022, link. El Bajío is an ejido, a collectively owned tract of land established in the early twentieth century in response to demands for land redistribution by rural communities. The privatization of ejidos had not been possible until constitutional reform in 1992. The origins of the term ejido itself and its imbrications with colonialism and dispossession, particularly in non-native ejidos, is something to contend with, specifically because the ejidos were created under Spanish colonization and served as a form of protection for Indigenous people before their abolition in 1857 by the independent state. For more details about the history of ejidos since their reestablishment by the Mexican Revolution in 1917, see Clara Eugenia Salazar Cruz, “La Privatisation des terres collectives agraires dans l’agglomération de Mexico: L’impact des réformes de 1992 sur l’expansion urbaine et la régularisation des lots urbains,” Revue Tiers Monde 206, no. 2 (2011): 95−114. ↩

-

Miguel Fernández de Castro and Natalia Mendoza, The Absolute Restoration of All Things, exhibition video, Storefront for Art and Architecture, 2022. ↩

-

They are Carmen Cruz Pérez, Abel Cruz López, Jacinto Cruz Pérez, and José Concepcion Cruz Pérez. ↩

-

Article Six of the ruling issued by Justice Manuel Loya Valverde. ↩

-

Fernández de Castro and Mendoza, The Absolute Restoration of All Things, exhibition newsprint, Storefront for Art and Architecture, 2022. In addition to restoring the ecosystem to its original state, the ruling required Penmont to make it free of all contaminating elements caused directly or indirectly by the company. See also “Tribunal Unitario Agrario Distrito Veintiocho,” (188/2009), 3. ↩

-

Chen Jie, “Death of the Desert,” China Dialogue, July 14, 2015, link. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

It is important to note here that the case against the eight companies in the Tengger Desert was filed by the lawyer for the state-sponsored China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation, whereas the case against Penmont was the result of action by people directly impacted by the expropriation and its resultant pollution. Moreover, the implications of the latter case are larger because they reject the state’s philosophy, which considers all territorial riches its property. The ruling thus grants the wealth potential of land to the people who live on the land. ↩

-

“Getting Creative in Quarry Restoration Design,” Quarry Magazine, February 1, 2007, link. ↩

-

The author has preferred the use of “community members” and “communities” instead of “Indigenous peoples” solely as a more representative term for the complex makeup of this particular society that includes both indigenous and peasant elements. Readers can refer to Natalia Mendoza, “Depoliticizing Conflict in Sonora, Mexico: (Il)legality, Territory and the Continuum of Violence,” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 112 (2021): 117-136. ↩

-

According to reports, a couple who was involved in activism against Penmont was murdered and the names of thirteen other activists were found on their bodies as a threat. See “Couple Who Challenged Sonora Mine Murdered; 13 Others Threatened,” Mexico News Daily, May 6, 2021, link. ↩

-

Haroon Siddique, “Mexican Farmers Demand Redress for Illegal Mining and Violence on Their Land,” The Guardian, May 17, 2022, link. ↩

-

Fernández de Castro and Mendoza, The Absolute Restoration of All Things, exhibition newsprint, Storefront for Art and Architecture, 2022. This phrasing is very close to the one found in case (188/2009), which was also issued by the same judge. ↩

-

See “Couple Who Challenged Sonora Mine Murdered; 13 Others Threatened.” ↩

-

Luz Cecilia Andrade, “El Bajío: El Ejido de Sonora Que Resiste Contra la Mina de Oro de Baillères,” Corriente Alterna, January 1, 2022, link. ↩

-

Fernández de Castro and Mendoza, The Absolute Restoration of All Things, exhibition newsprint, Storefront for Art and Architecture, 2022. ↩

-

Email communication with Natalia Mendoza. ↩

-

James Young, “The Counter-Monument: Memory against Itself in Germany Today,” Critical Inquiry 18, no. 2 (Winter 1992): 277, 281. ↩

-

Interested readers should refer to Samia Henni’s edited volume Deserts Are Not Empty (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022). ↩

-

See “Couple Who Challenged Sonora Mine Murdered; 13 Others Threatened.” ↩

-

See the author’s contribution to Deserts Are Not Empty, 32−33. ↩

-

See Judith Sunderland and Lorenzo Pezzani, “EU’s Drone Is Another Threat to Migrants and Refugees,” Human Rights Watch, August 1, 2022, link. ↩

-

Urrea, The Devil’s Highway, 19. See also the author’s contribution to Deserts Are Not Empty, 32−33. ↩

-

Carl Lumholtz, New Trails in Mexico: An Account of One Year Exploration in North-Western Sonora, Mexico, and South-Western Arizona, 1909−1910 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912). ↩

-

Of particular note is Lumholtz’s acknowledgment that he was “commissioned by some influential friends to look into certain economical possibilities of the arid and little known [sic] country along the upper part of the Gulf of California, east of the Colorado River… My mission gave me an opportunity for geographical and ethnological studies, an account of which is here presented in popular form.” See Lumholtz, New Trails, vii. ↩

-

Lumholtz, New Trails, ix. ↩

-

Isabelle Eberhardt (1877−1904) is emblematic in this regard. On the one hand, she loved the desert, married an Algerian, and wrote about living in a desert town. On the other hand, she served as a spy for an enterprise to conquer Morocco, and her encounter with Indigenous communities was characterized as an impudent propensity to extract resources from them without ever paying anything back. Eberhardt’s is just one example of the extraction of desert people’s resources, which has taken many forms, ranging from mining to labor and sustenance. All one needs to do is to read closely to find the racializing biases that govern most Saharanist works. Other Saharanists include René Caillié (1799–1838) in the Sahara, Ernest Giles (1835−1897) and Charles Sturt (1795−1869) in the Australian desert, and Charles Montagu Doughty (1843–1926) and St John Philby (1885−1960) in the Arabian Desert. ↩

-

While connections and similarities exist between Orientalism and Saharanism, it is important to avoid conflating the two, as they are very different in terms of scope and subject matter as well as in the histories of violence embedded in each. ↩

-

Abdulrahman Munif, Mudun al-milḥ: Riwāyah (Beirut: al-Mu’assassa al-‘Arabīyya li-al-Dirāsāt wa-al-Nashr, 1985); Umar al-Shihābī, “Al-Bīy’a wa-mudun al-khalīj al-nifṭiyya,” Markaz al-Khalīj li-Siyyāsāt al-Tanmiyya, Gulf Centre for Development Policies, link. ↩

-

For a study of Saharan Gothic in Arabic literature, see Brahim El Guabli, “Saharan Gothic: Desert Necrofiction in Maghrebi and Middle Eastern Desert Literature,” in Middle Eastern Gothics, ed. Karen Grumberg (Cardiff: Wales University Press, 2022), 187−209. ↩

-

Ali Dogan, a research fellow at Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, has written that “Neom, as MBS’ own megaproject, serves as key tool for him to consolidate his power in Saudi Arabia and foster the regime’s security.” See “Saudi Arabia’s Neom Diplomacy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 3, 2021, link. ↩

-

Just in the summer of 2022, there have been: Business Week’s “MBS’s $500 Billion Desert Dream Just Keeps Getting Weirder,” Slate’s “Line in the Sand, Head in the Clouds,” Financial Times’ “Saudi’s Neom Is Dystopia Portrayed as Utopia,” the Washington Post’s “Saudi Crown Prince Wants You Talking about His ‘City of the Future,’” and NPR’s “A 105-Mile-Long City Will Snake through the Saudi Desert. Is That a Good Idea?,” among others. ↩

-

Mariam Nihal, “The Line in Neom Is ‘the Greatest Real Estate Challenge That Humans Have Faced,’” National News, August 16, 2022, link. ↩

-

Dania Akkad, “Neom: Saudi Arabia Sentences Tribesmen to Death for Resisting Displacement,” Middle East Eye, October 7, 2022, link. ↩

-

As I have already mentioned, most major international news outlets covered the launch of Neom. Several articles noted the unlikely realization of such a costly and science-fictional city (a particularly critical article was written by Henry Grabar for Slate under the title “Line in the Sand, Head in the Clouds”). However, the desert itself as an object of transformation has been mostly absent from critiques. Mohammed bin Salman understands the appeal of Saharanist tropes, stating that “the Line will tackle the challenges facing humanity in urban life today and will shine a light on alternative ways to live.” In other words, the desert is presented as a hyper-modern refuge for those disillusioned with Euro-America. See Naama Riba, “Neom and The Line: Saudi Arabia’s Futuristic City Already Belongs in the Past,” Haaretz, August 2, 2022, link. ↩

-

Historian Benjamin Brower, examining the French encounter with the Sahara in the nineteenth century, has noted French Saharanism’s vision of the desert as an inherently hostile space. Hostility vis-à-vis an inhospitable space, combined with notions of emptiness, enabled practices of “experimental extraction” in the Sahara in the 1960s. Benjamin Brower, A Desert Named Peace: The Violence of France’s Empire in the Algerian Sahara, 1844−1902 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 200. ↩

-

Elizabeth Leuvrey’s 2016 film A(h)ome provides a crucial depiction of the native Saharan’s experience of French nuclear tests and their lasting impact on their lives. ↩

Brahim El Guabli is Assistant Professor of Arabic Studies and Comparative Literature at Williams College. His forthcoming book is Moroccan Other-Archives: History and Citizenship after State Violence (Fordham University Press). He is currently completing a second book, titled Saharan Imaginations: Between Saharanism and Ecocare.