In the forested southeast corner of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, in the mold provided by an underutilized ravine, there is a living memorial.1 It was cultivated in the early 1990s in the midst of the AIDS epidemic and is dedicated to the memories of a generation of LGBTQ+ people who were lost to the disease. The site is maintained in large part by community labor through regular volunteer workdays—a continued practice of care, or tending to the site, that serves as an ongoing trial in community placemaking and collective memory. In 1996, the space was federally recognized as the National AIDS Memorial Grove and designated a national memorial. It is a beloved space, though it has reached a peculiar inflection point: According to factions of the local community, some LGBTQ+ community leaders, national and municipal politicians, design consultants, and the memorial’s governing board, the Grove alone isn’t cutting it anymore as a site of national remembrance. Central to this discourse around the memorial’s design and how it has aged since its inception is an understanding that something fundamental is missing—yet there is little consensus as to what, exactly, that is. Though often seen as a critical step in bringing the AIDS epidemic to the national consciousness, this federal designation also functions as the source of growing anxiety over the Grove’s future.

It is not a fatal act to seal a history in bronze or stone. Rather than kill, it repackages—and that repackaging may, in time, prove insufficient to contain what’s alive within. The dilemma posed by the AIDS Memorial Grove does relate to its design, but it is more nakedly existential. How can a history be (physically) produced, or reproduced? This discourse over the purpose of the Grove—for whom it is intended, by whom it is constituted, and what its responsibilities are as a site of personal, traumatic, and national memory—reveals the profound growing pains of a memorial born in the very midst of an epidemic that has since, in many ways, been quelled. If the Grove must change, then how? Here I engage with other built memory works, specifically Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial as well as another AIDS memory project, the AIDS Quilt, to evaluate the stakes of the given dilemma.

The Grove

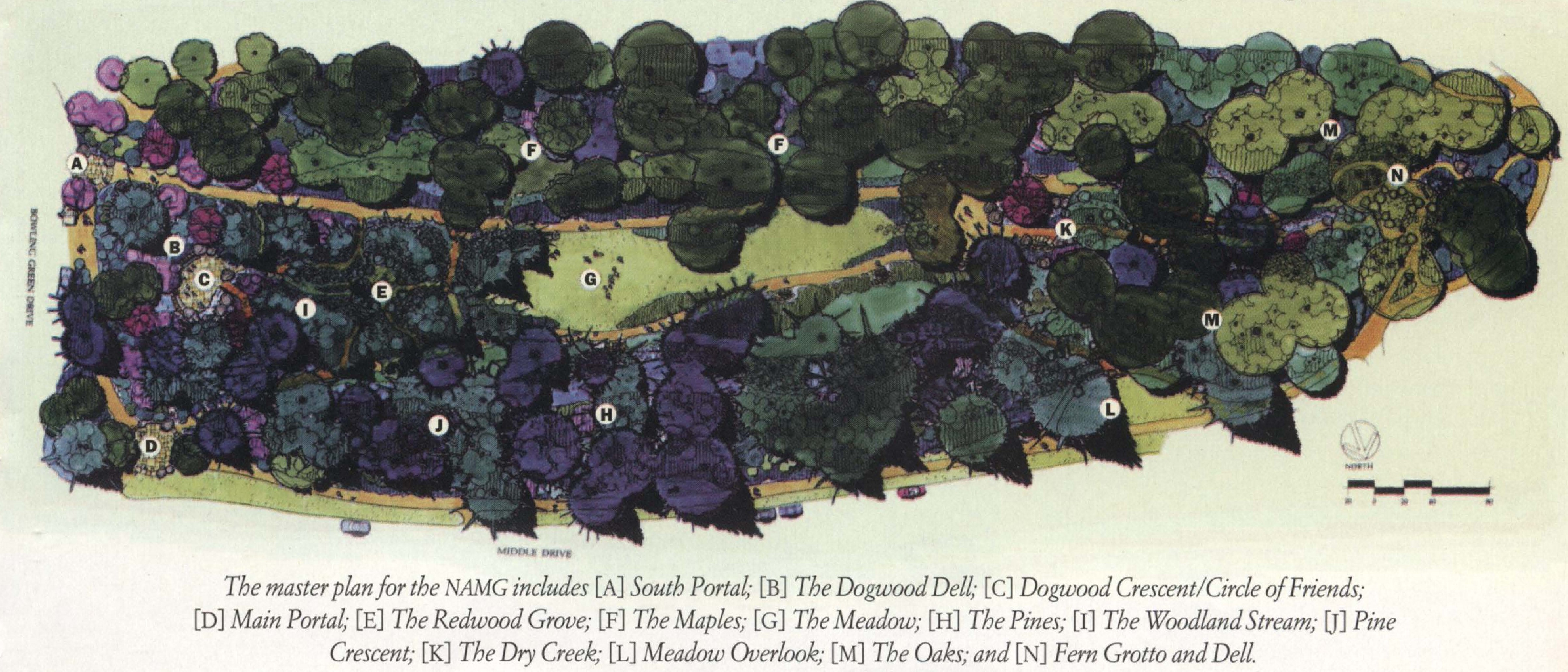

The Grove first took shape in 1988 when six San Franciscans, each involved in urban environmental groups or landscape design, conceived of a space where community members could gather to mourn and remember friends and family lost to AIDS-related complications.2 This group consulted with the modernist landscape architect Garrett Eckbo through the design process, a relationship that, according to landscape scholar Clare Cooper Marcus, was meant “principally to establish credibility for the idea of the grove in the eyes of the Recreation and Parks Department.”3 The team chose as their site the de Laveaga Dell, an underutilized sector of Golden Gate Park, which for the group held great potential. Marcus expands on this point:

[The site] was easily accessible by bus, automobile, and on foot from residential areas of the city; its ravine-like topography created an enclosed setting, from which nearby road traffic could be neither seen nor heard; a central, flat meadow provided a space where large gatherings might occur; tall pines and redwoods and some specimen shrubs provided a vegetative framework; and a dry streambed at the western end of the valley provided varied terrain.4

Construction began in September 1991 with the first of an ongoing series of community workdays.5 The fact that community labor was built into the project from the beginning points to the larger purpose of the space. In a 1999 evaluation for the prestigious Rudy Bruner Award, a selection committee argued that the “central value embodied in the Grove’s development is the importance of process.”6 The Grove was born out of this desire to engage with the local community through collective grieving, or as sociologist Joshua Gamson has expressed so clearly: “taking care of the land was understood as a mechanism for coping with traumatic memory.”7 From the initial construction of the project to its later reception, the space has been widely interpreted as one where community members can exercise grief through the physical reworking of landscape, and through this reworking keep memory alive. Process—as continued upkeep, or as a state of grieving or remembering—is paramount.

The physical result is this: a series of gathering spaces dictated by changes in topography or vegetation. There is an oblong central meadow bounded at the north and south by slopes covered in grasses and trees. To the east, the meadow gives way to a redwood forest set amid a wide streambed. Here, one can typically find cairns assembled by visitors. Beyond the redwoods is the Circle of Friends, a flat stone engraved with the names of some 2,500 individuals affected by the epidemic. West of the meadow is a second meeting point called Fern Grotto, which is reached via two paths set on either side of a stream. Another pathway straddles the height of the northern slope. At one vantage point along this elevated path, a series of seven polished granite plaques are set into the lip of a stone wall. Together they display a condensed timeline of the epidemic—the only overt narrative work within the memorial site. On the July day I visited, I found the fifth plaque was missing. It had been mysteriously plied from its stone base, the effect being that several years were absent from the timeline. Taking the steps that lead down from this overlook brings visitors back into the grassy dell.

The Grove was built at and for a specific scale of use. Because it was conceived at the height of the early US AIDS epidemic, it was intended primarily as a site of individual and collective grieving; the intimate scale of the space is designed to facilitate this grieving process. Upon receiving its national designation in 1996—“H.R. 3193: To recognize the significance of the AIDS Memorial Grove, located in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, California, and to direct the Secretary of the Interior to designate the AIDS Memorial Grove as a national memorial”—the Grove was thrust into an entirely different scale of use.8 As Gamson elaborates, “the functions of semiprivate grieving, healing, and remembrance came into competition with the function of public storytelling, oriented towards a national audience in both the present and the future.”9 Though not mutually exclusive, personal grieving and national memorializing each have their own unique spatial requirements.

This tension between the personal and national—or even international—also has implications for the groups or identities the memorial is intended to serve. Given the “early trajectory of HIV/AIDS in San Francisco,” the Grove is in large part a gay memorial—which, as oral historian Horacio Roque Ramírez argues, can center “particular demographic sectors (the middle and upper classes, typically white and male but not exclusively).”10 The Grove’s governing board has taken some institutional steps to diversify this constituency, particularly through its outreach and public programming.11 The board has also considered the ongoing effects of AIDS more broadly—conceptually and geographically—further expanding its reach.12 The institutional efforts to include these various and potentially overlapping constituencies point to an underlying problem. Historian Susan Crane describes this as the difference between collective and historical memory, where collective memory is by definition multiple, and historical memory runs the risk of flattening this multiplicity within a single narrative.13 National memorials typically require the latter approach. The danger here is that the specificities of each constituency might be “generalized and reduced to simply people who died from AIDS, or ‘AIDS victims.’”14

It has since become apparent to some that the Grove is, in its current form, unable to fulfill these requirements of a national memorial. Board member Mike Shriver gives voice to this challenge: “The grove is like a beautiful poem… it grows, it dies, it follows all the life patterns, it’s all architecturally based on loss and pain… but I think it’s way too subtle.”15 The Grove currently deals in nuance. It provides the space for a particular mode of personal grief but relies on the visitor to fill in the narrative blanks. Such is the apparent limitation of a landscape-sited memorial. As another board member argues, “It is very hard to tell a very complex story outdoors.”16 To those recently tasked with rethinking the Grove’s design, a memorial, “like other ‘memory projects’ or ‘sites of memory’ such as museums and monuments,” must include more overt narrative gestures like signage or built structures.17 In shouldering the responsibility to communicate a national, rather than local and personal, narrative of the AIDS crisis, the Grove’s governing board has looked to augment the space with these or similar additions.

Amending the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

There is a well-known precedent for this kind of problem: Maya Lin’s salient 1982 Vietnam Veterans Memorial, which was criticized in its time for mishandling the responsibilities of a national memorial. This project is a dominant subject for contemporary historians, sociologists, and anthropologists who practice in memory studies, both for its radical subversion of traditional war memorializing and its contested reception. Cultural critic Marita Sturken elaborates:

The traditional war memorial works to impose a closure on a specific conflict… In declaring the end of a conflict, this closure can by its very nature serve to sanctify future wars by offering a completed narrative with cause and effect intact. In rejecting the architectural lineage of monuments and contesting the aesthetic codes of previous war memorials, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial also refuses the closure and implied tradition of those structures; yet it both condemns and justifies future memorials.18

Lin’s design, a physical rift in the ground that exposes a polished, black stone wall with carved names, decenters the political context of the Vietnam War, focusing instead on the loss of the individuals themselves. The design uses landscape to make this point. As the visitor descends the sloped pathway that abuts the wall, the wall grows taller, and the names grow in number. The memorial’s apoliticism is, of course, a political stance. Responses were visceral. According to sociologists Robin Wagner-Pacifici and Barry Schwartz, critics saw Lin’s break from aesthetic tradition as presenting a “nonpatriotic and nonheroic” message, instead imbuing the memorial with a sense of shame.19 In response to these critiques, changes were made to the memorial shortly after its unveiling. These included a flagpole, plaques, and The Three Soldiers, a bronze statue by artist Frederick Hart depicting servicemen in action. Historian Meredith H. Lair argues that each “of these addenda to the memorial represented a constituency that argued that its needs were unmet by the original design.”20 The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is now considered en masse, with Lin’s design and these built interventions linked together under the same header. As a further corrective, an education center that would act as a political and cultural counterpart to the memorial was planned for an adjacent site, though this effort was canceled in 2018 due to challenges with fundraising.21

If each addendum to the site is considered a kind of argument—an additional layer of complexity, a rebuttal, a delayed inclusion, or a deliberate exclusion—they can together be read as a material historiography; here one can see the tensions that arise when a site is challenged with producing a definitive history. It is in this spirit that the AIDS Memorial Grove is so often put into conversation with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, its failings framed by or against the legacy of Lin’s design. Like Lin’s granite gash, the Grove is a nontraditional space that resists easy closure. Its ability to produce a national history of the AIDS crisis is indeed limited by its focus on individual mourning. Yet, if the example of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is to be followed, it might soon become a landscape littered with material amendments.

“Emergent Memory”

In 2005, the Grove’s governing board launched an international design competition styled “Emergent Memory: The National AIDS Memorial Competition.” The brief laid the issue bare: “For many supporters of the Grove, the need for a signature memorial element—a physical manifestation of the status designated by Congress that would broaden the Grove’s power to address the national and global impact of AIDS—came to the fore.”22 The competition drew some two hundred proposals. A jury of artists, curators, and architects (Sunil Gupta, Walter Hood, Mary Miss, Toshiko Mori, and Joseph Rosa) picked a winning entry titled Living Memorial: a “charred-wood viewing deck, a stand of black fiber rods with mirrored tips evocative of burnt trees, and a charred walkway where new plants would grow,” designed by Janette Kim and Chloe Town.23 This winning proposal was abandoned after a vocal public outcry labeled the design intrusive. The outfall from the failed competition fractured the governing board.24

In conversations with John Cunningham, the executive director of the National AIDS Memorial (who came aboard well after the 2005 competition), it’s clear that the ramifications of these proposals are still freshly felt among the current board.25 According to Cunningham, “There wasn’t enough definition in what the board wanted”—and here, familiarly, is the crux of the issue. Interestingly, the open-endedness of the brief gave way to a particular representational style. In what may be attributable to some aesthetic hang-up of the early aughts, many of the highlighted proposals incorporated assemblages of rods, poles, or reeds, some equipped with fiber-optic lighting. A few used topography or angled walls to constrict the visitor into narrowed spaces. Overwhelmingly, the proposals attempted to create a physical experience of discomfort—a mountain of stones in the central meadow, a barrage of sticks one must wade through—as if the emotional distance between the viewer and the historical subject might be bridged through a sensory simulacrum.26

In a subsequent monograph about the competition, an introduction by Neal J. Z. Schwartz speculates on the outcome: “No one can yet delineate the bounds of AIDS or the contours of its meaning. Like trying to imagine the limits of the sky, the best we can hope for are tools for fathoming. Perhaps the Living Memorial will become one such tool.”27 Fathoming suggests a kind of emotional depth and comprehension, and the submitted proposals certainly take that on in their attempt to produce a sensory response via devised installations. The difficulty here is to turn the emotional weight of the Grove outward, to make it legible and perceptible to a larger, unconnected public. With this approach, an AIDS history is conveyed not through direct narrative but rather through metaphor. In the decades-long attempt to find a suitable solution, other language has been used: the Grove should be a shrine (Marcus writes of the “family or friends [who] sometimes inter the ashes of a loved one at the grove…”)28; it should impart a set of values; it should protect memory, or act as a buttress against the inevitable passing of time; it should tell a political story, or maybe an apolitical one. Often these aims are counterintuitively conflated, as if they work toward the same end. Regardless, the 2005 competition made plain that a one-time installation in the Grove wouldn’t do the trick.

A 2017 New York Times article describes a then-nascent effort to construct a national AIDS museum near the Grove, a “place to chronicle the AIDS tragedy more comprehensively, to explore the pandemic’s many facets in a permanent national exhibition and repository.”29 Cunningham has hinted that this is the direction the organization is currently headed, though he is guarded about the specifics—understandably so, given the aftermath of the 2005 competition. The New York Times calls the proposal a museum, but Cunningham says otherwise: “This is not a museum.”30 The anxiety here is to prevent a kind of passive storytelling, or a reliquary, which the idea of a museum suggests. The board hopes for something more active, engaging, and provoking, and so has substituted “museum” with “Interpretive Center for Social Conscience.”31 This name flirts with the passive but has its roots in the “nomenclature adopted by the National Park Service after World War II to identify its interpretive facilities at parks and monuments,” according to historian Russell W. Fridley.32 Interpretive centers are found, notably, at the sites of Japanese Internment Camps, where traumatic and complex histories—histories that confront and question an American morality that is typically found in other national memorials—require a form of active interpretation on the part of the visitor. As the Grove looks to assume its national role, and as it necessarily tells a complex story about government inaction and the ongoing decimation of marginalized groups, the model of the interpretive center seems like a viable path forward compared to traditional forms of national memorializing. But its relationship to the existing Grove and how the two might work together or separately remains unclear. Part of the center’s ambition is to situate the AIDS crisis in “the greater struggle for social justice throughout history,” a narrative broadening that once again puts the Grove’s particular scale into question.33

The AIDS Quilt Comes Home

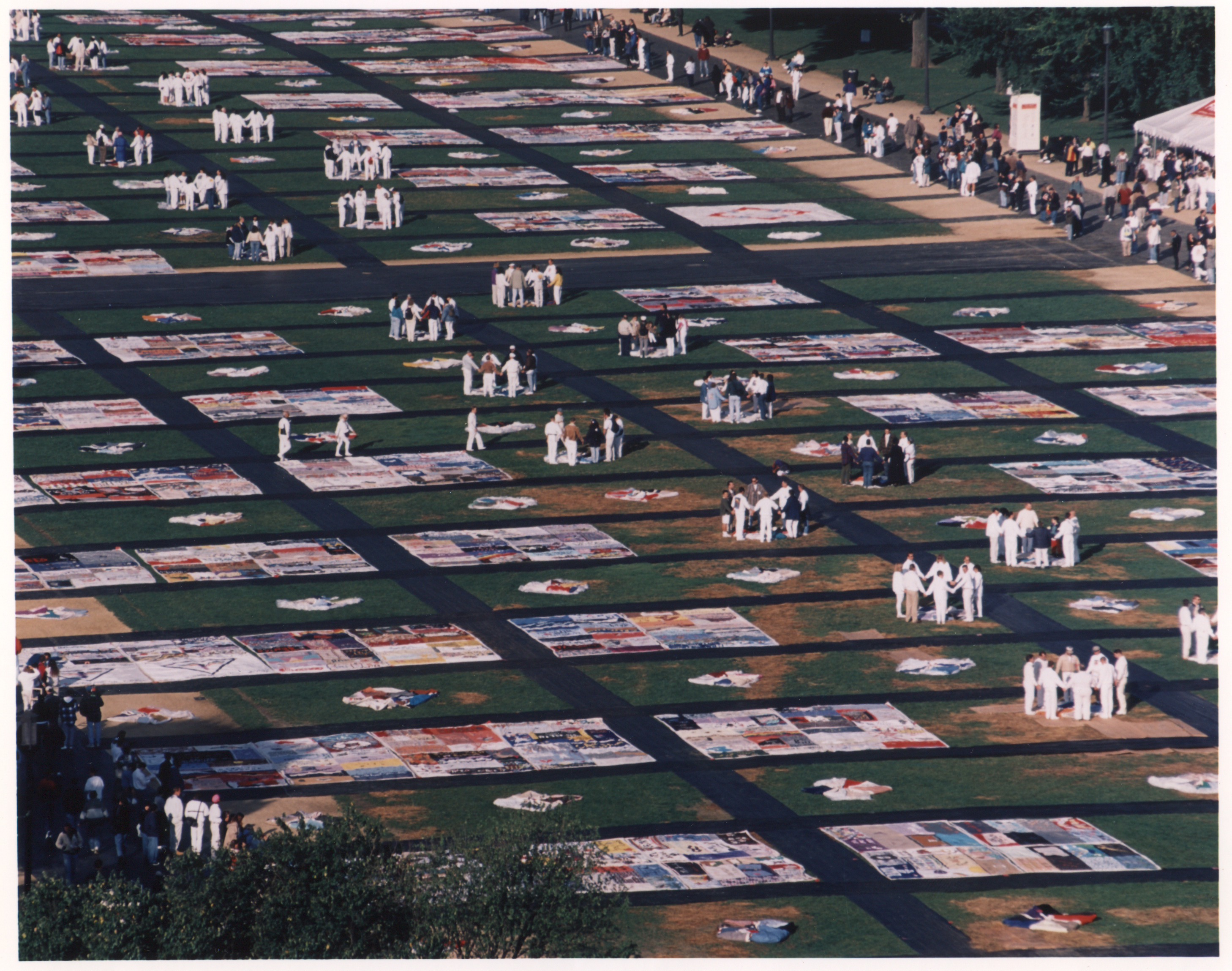

Another AIDS memory project, the AIDS Quilt, was conceived by activist Cleve Jones in San Francisco in the same year that the Grove was taking shape—“just down the street from each other,” adds Cunningham.34 At once a commemorative project and a political instrument, the Quilt is made up of individual 3-by-6-foot stitched panels—a symbolic nod to the standard dimensions of a coffin—that feature the name of someone lost to AIDS-related complications. There may be stitched mementos, memorabilia, or embellishment, or not; it is at the discretion of the maker, most often a friend or family member, but in some cases a stranger. The Quilt’s debut at the 1987 San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Freedom Day Parade featured forty of these panels. Later that summer, the Quilt, then at 1,920 panels, was laid out on the National Mall. This would occur again in 1989, and in 1992, and in 1993, the Quilt having grown in each subsequent appearance.35 In its 1996 installation, the Quilt covered the entire length of the Mall. Now-famous images of the event show an immense assemblage of hand-stitched panels stretching from the Washington Monument to the Capitol.

Here is where the Quilt moves from the commemorative to the political. Its unveiling was an activist response to a callous federal government that refused to acknowledge or act against AIDS because of the stigma attached to it by its predominantly LGBTQ+ victims. Its success as a political instrument is intimately tied to its ability to take up space; the Quilt demands to be seen. Its aggregate form—assembled panels, each year growing larger—conveys a massiveness, an ever-compounding loss, that is deployed toward political ends. But the Quilt also exists at the scale of the panel, of the named, remembered individual. Memory is conveyed through each unique panel; narrative is conveyed when one zooms out. What is remarkable about the Quilt is that it can function so effectively at these multiple spatial scales and so can take on both commemorative and political qualities quite readily.

In November 2019, in a televised conference at the Library of Congress, Julie Rhoad, then the CEO and president of the NAMES Project Foundation, announced that the AIDS Quilt would be returning to San Francisco after a long period of storage in Atlanta, under the new stewardship of the National AIDS Memorial.36 The reception of that announcement is reminiscent of a homecoming. The Quilt will now exist alongside the Grove under the same header: the National AIDS Memorial. There seems to be a reflexive quality to this homecoming as well, where the Quilt—the more well-known of the two—is strengthened as a site of memory in its union with the Grove, and vice versa. According to Cunningham, this acquisition was fortuitous, and plans for the Interpretive Center for Social Conscience were put on hold while the board saw the acquisition through. If or when the Center is realized, it will hold the aggregate Quilt in exhibition and “allow for visitors to request individual panels to be pulled for viewing.”37 This method of display, where the Quilt’s dual scales as a commemorative and narrative project are highlighted, seems equipped to convey a history of the AIDS epidemic—and potentially relieve some of the pressure that has weighed on the Grove for decades.

Is this homecoming a kind of closure? Does it retire the Quilt as a political instrument? And if the job appears finished, will the Grove finally be at peace, able to absorb and reflect memory on its own terms? Curator Timothy P. Brown says that a “history shaped by traumatic violence becomes not a history that is recorded, explained, and resolved for all time but a history that is essentially not over.”38

Unveiling

What was not so fortuitous was the timing of the Quilt’s acquisition. The National AIDS Memorial intended to display two thousand panels in a meadow adjacent to the Grove on April 4, 2020, an event that would coincide with celebrations for Golden Gate Park’s 150th anniversary. These plans were scrapped in early March as the emergence of COVID-19 triggered shutdowns across the country and world. The Quilt remains in storage in the East Bay while the pandemic continues. Meanwhile, the Grove has stayed more-or-less open to the public.

In July 2020 the National AIDS Memorial decided to film a pared-down unveiling of the Quilt.39 The video shows eight volunteers, each clad in white clothing and face masks, as they participate in an unfolding ritual with a small square of connected panels. This ritual is meant to mimic the unfolding ceremonies that occurred in each of the Quilt’s appearances at the National Mall, where teams of volunteers worked to display the Quilt in a piecemeal fashion. Aided by aerial drone imagery, the video zooms out to reveal the central meadow and, later, the Grove itself. The Grove bounds the ritual. It is work to unfold the Quilt; the Grove’s mowed lawn, its measured gravel paths, betray labor.

The Grove and the Quilt are successful memorials because they require this work. They need to be stitched, folded, sowed, watered. This kind of sustained care is one method of negotiating, rescripting, and transferring memory—which can be resolved but is more likely to be wrestled with. The anxieties of past decades, lingering questions of completeness and resolution, are not an indicator that something about the Grove remains broken; rather, they indicate that the Grove is, and has been, working. The video frames the Grove in this capacity, as a living architecture that accepts the multiscalar tensions that are essential to traumatic memory. This is, again, counter to the ideological imperatives of the typical national memorial—but as each now bears that national memorial title, the Grove and the Quilt necessarily call those traditional notions into question.

Thank you to John Cunningham and Kevin Herglotz of the National AIDS Memorial for their time and generous conversations.

-

This research was funded by an SEF Grant from Harvard GSD. ↩

-

This group included Alice Russell-Shapiro, Nancy McNally, Stephen Marcus, David Linger, Isabel Wade, and Jim Hormel. They were joined by landscape architects Michael Boland and William Peters and later formed a larger board composed of architects, planners, and other development professionals. ↩

-

Clare Cooper Marcus, “Act of Healing—At the National-AIDS-Memorial-Grove, Restoring a Landscape Has Helped Comfort and Restore Those Touched by AIDS,” Landscape Architecture 90, no. 11 (2000): 78. ↩

-

Clare Cooper Marcus, “Act of Healing,” 77. ↩

-

The Grove has been largely built and maintained by community efforts, though the space does employ one full-time gardener. ↩

-

Robert Shibley, et al., “National AIDS Memorial Grove,” Commitment to Place: Urban Excellence & Community (New York: Bruner Foundation, Inc., 2000), 96. ↩

-

Joshua Gamson, “‘The Place that Holds Our Stories’: The National AIDS Memorial Grove and Flexible Collective Memory Work,” Social Problems 65, no. 1 (2018): 41. Gamson’s piece is one of the few scholarly works on the National AIDS Memorial Grove. It cogently evaluates the institutional history of the Grove, framing memory production as a complex process of organizational and cultural decision-making. ↩

-

“AIDS Memorial Grove Act of 1996,” 104th Congress, 2D Session, House Report 3193. ↩

-

Joshua Gamson, “‘The Place that Holds Our Stories,’” 41. ↩

-

Joshua Gamson, “‘The Place that Holds Our Stories,’” 41. Horacio N. Roque Ramírez, “Gay Latino Histories/Dying to Be Remembered: AIDS Obituaries, Public Memory, and the Queer Latino Archive,” Beyond El Barrio: Everyday Life in Latina/o America, eds. Gina M. Pérez, Frank A. Guridy, and Adrian Burgos, (New York: NYU Press, 2010), 106. ↩

-

This includes the National AIDS Memorial’s Pedro Zamora Scholarship and Mary Bowman Arts in Activism Award, as well as a recently launched storytelling initiative, “2020/40,” which exhibits multimedia narratives from or about individuals affected by the epidemic. ↩

-

This broadening has most recently taken the form of the Hemophilia Memorial, a 2017 addition in the style of the existing Circle of Friends flat stone, which serves a constituency that is not necessarily tied to an LGBTQ+ identity. Toward the global, the National AIDS Memorial has widely publicized this quote from Rep. Nancy Pelosi: “Thousands of people have died in San Francisco, millions in the world. The point of the National AIDS Memorial Grove is to remember them, one at a time.” This quote is also inscribed in a stone paver at one of the Grove’s entryways. From “About,” National AIDS Memorial, link. ↩

-

Susan A. Crane, “Writing the Individual Back into Collective Memory,” The American Historical Review 102, no. 5 (December 1997): 1,374. ↩

-

Horacio N. Roque Ramírez, “Gay Latino Histories/Dying to Be Remembered,” 105. ↩

-

Joshua Gamson, “‘The Place that Holds Our Stories,’” 42. ↩

-

Joshua Gamson, “‘The Place that Holds Our Stories,’” 42. ↩

-

Joshua Gamson, “‘The Place that Holds Our Stories,’” 36 ↩

-

Marita Sturken, “The Wall, the Screen, and the Image: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial,” Representations, no. 35 (Summer 1991): 122. ↩

-

Barry Schwartz and Robin Wagner-Pacifici, “The Vietnam Veterans Memorial: Commemorating a Difficult Past,”American Journal of Sociology 97, no. 2 (September 1991): 395. ↩

-

Meredith H. Lair, “The Education Center at the Wall and the Rewriting of History,” The Public Historian 34, no. 1 (Winter 2012): 38. ↩

-

“Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund Changes Direction of Education Center Campaign,” Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, link. ↩

-

Neal J. Z. Schwartz, et al., Emergent Memory: The National AIDS Memorial Competition (San Francisco: National AIDS Memorial Grove, 2005), 4. ↩

-

Joshua Gamson, “‘The Place that Holds Our Stories,’” 40. ↩

-

The institutional challenges of this 2005 competition are the subject of the 2011 documentary The Grove, directed by Andrew Abrahams and produced by Tom Shepard. ↩

-

John Cunningham, personal interview, September 23, 2020. ↩

-

A selection of these proposals can be seen in the Schwartz monograph. I am most directly referencing the projects Beyond Quantity, by Raveevarn Choksombatchai, Jacob Atherton, Michael Eggers, and Andrew Shanken; Memory Stones, by Melissa Cate Christ; Fissure, by Joseph Barajas, Michael Boone, Patrick Flynn, and Daniel Robb; and Constellations of Hope, by Johannes Feder, Barbara Wilks, and Alex Washburn. ↩

-

Neal J. Z. Schwartz, Emergent Memory, 14. ↩

-

Clare Cooper Marcus, “Act of Healing,” 95. ↩

-

Scott James, “An AIDS Museum: The Challenges Are Huge, but the Timing Is Right,” New York Times, March 13, 2017. ↩

-

John Cunningham, personal interview, September 23, 2020. ↩

-

Russell W. Fridley, “Interpretive Centers: An Indigenous Minnesota Idea that Is Thriving!” Minnesota History 45, no. 1 (Spring 1976): 32. ↩

-

John Cunningham, personal interview, September 23, 2020. ↩

-

Peter S. Hawkins, “Naming Names: The Art of Memory and the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt,” Critical Inquiry 19, no. 4 (Summer 1993): 757–760. ↩

-

Richard Gonzales, “AIDS Memorial Quilt Is Returning Home to San Francisco,” NPR, November 20, 2019. ↩

-

John Cunningham, personal interview, September 23, 2020. ↩

-

Timothy P. Brown, “Trauma, Museums and the Future of Pedagogy,” Third Text 18, no. 4 (2004): 258. ↩

-

“Message from National AIDS Memorial Executive Director John Cunningham,” National AIDS Memorial, July 4, 2020. link. ↩

Jacob Cascio is a second-year master in landscape architecture candidate at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He holds a BA in history from Reed College.