Emptiness

Arriving in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, the journalist Ian Birrell recounts a luxurious, modern, but strikingly empty city: a lifeless “land of artifice.”1 Traveling with a parliamentary delegation from Britain and taking note of how insulated such excursions are from everyday Equatorial Guineans lives, Birrell was tasked with scrutinizing Equatorial Guinean politics, his Western democratic viewpoint more focused on the autocratic rule of President Teodoro Obiang than on corporate interests that subtend that rule. On his drive from the airport, he passes impressive structures—offices, flats, mansions for each African leader participating in African Union affairs. Yet these buildings remain largely unoccupied. The Sipopo Congress Center, designed by the Turkish architecture firm Tabanlιoğlu Architects, is one of these buildings. Its elaborate patterns and textures, and its transparent façade, are boastful—an aesthetic that highlights how alienated the structure is from the country’s everyday inequalities. The building was constructed in just six months in 2011. Its glass exterior is consistent with other recent large-scale building projects in Equatorial Guinea—which together evidence the cultural, aesthetic, and infrastructural value of oil and the way resource-rich landscapes come to be dominated by a particular breed of “white elephants,” as anthropologist Hannah Appel has argued.2

Driven by profits from oil extraction, the Sipopo Congress Center presents itself as a prototype of the so-called modern development projects emerging in Equatorial Guinea. But the politics and economy of oil complicate the functions of these sites, particularly when the extent of the country’s inequality is foregrounded. The absence of democracy, of adequate critical infrastructure, and of basic necessities complicates the notions of “development” and “modernity” employed by both the industrialists and architects of these projects. Oil extraction enables development while simultaneously reproducing exploitation. In producing excess for some, extractive development actively produces lack for others: “As built responsibility, the conspicuousness of white elephant projects and the haste with which they go up—often cited as evidence of their hollowness—are in fact integral to their function,” writes Appel.3 The Sipopo Congress Center is a site of visible state investment that conceals the conditions of its production. The building detaches itself from its undemocratic landscape, both in terms of Equatorial Guinea’s autocratic government and the global corporatism of oil extraction. Its primary function may be to host political conferences of the African Union, but this stated mission comes into conflict with its effective production of state-citizen relations. This site, then, is inseparable from the modes of exploitation that perpetuate local inequalities in the name of creating a supposedly modern future.

Citizens of Modernity

Contemporary capital investment, and the forms of development that enable oil extraction in particular, have often been described as existing in a space of global fluidity that exceeds the boundaries of the nation-state.4 Projects such as the Sipopo Congress Center, in contrast, sit ambiguously within national space. On the one hand, the building can be seen as an expression of a more general ambition described by David Adjaye as an “architecture of governance,” intended to promote a constructive relationship between governments and citizens.5 While the building maintains a certain image of the state, its elaborate appearance also shows just how far removed it is from the daily realities of Equatorial Guineans. This complicates the intentions of producing a kind of state-citizen unity—an “African Harmony”—that its architects, the Turkey-based Tabanlιoğlu Architects, claim to have had in mind.6

Malabo, the capital of Equatorial Guinea, is situated on the island of Bioko, separate from the country’s continental territory. The design of the Sipopo Congress Center gestures toward this locality. The entrance lobby nods to it, too, with a map of Africa illuminated by LED lights, on which Equatorial Guinea’s Bioko island shines red in contrast to the yellow lights that animate the rest of the continent. Although this is meant to signal a sense of inclusiveness and African identity, this graphic also betrays its attachment to the imagined nation since it is the island rather than the national continental space that is highlighted. Behind the map, a geometric pattern casing the lobby wall is presumably meant to reflect traditional African patterns, while the use of timber and the bark of pine trees references Equatorial Guinea’s natural resources.7 Yet, the emphasis on the larger African identity further deviates from Equatorial Guinean specificities.

Mario Gooden has written about how architecture needs to “become a form of knowledge” rather than a display of “tropes, superficial ‘africanisms,’ and token symbols of a mythologized African landscape.”8 While Gooden is critiquing the architecture meant to represent African American identity—describing how the inclusion and use of graphical patterns associated with Africa have “the intention of maintaining white power structures and social hierarchies”—the thought similarly applies to the geometric patterns implemented by the Turkish architecture firm. Gooden explains that this “preoccupation with the image of architecture and its superficial aesthetics” have placed black Americans on “the minus side of the calculations” against white Americans.9 Equatoguineans are placed in the same way, denying their access not just to history but to political representation. Alongside this, the firm explained their intention to distinguish the conference center from both the colonial architectures distributed across the African continent as well as buildings constructed by “local people without architects.”10 The resulting generalized, Africanized design dismisses the country’s specific history and culture in its imagination of a more “universal” modern future.

The empty aesthetics of the Sipopo Congress Center reveals another dynamic in the absent relationship between Equatorial Guinea’s government and citizens. Just as oil extraction employs few (if any) local residents, the outsourcing of both the design and construction suggests a similar disregard for cultivating expertise or supporting local industries.11 The choice to commission Tabanlιoğlu Architects—made by President Obiang, who has held the office since the coup of 1979—meant that all the participants (architects, engineers, and consultants) were based in Turkey while the contractor, Summa, imported the majority of the materials.12 The complex’s discourse of African unity distracts from the state deployment of infrastructure as a means to justify the present relations between the state and its citizens.13

In positioning their building against both colonial and vernacular forms, Tabanlιoğlu Architects are drawing on a common trope—connecting glass structures to development discourses and temporalities that distance such buildings from a meaningful relationship with the nation. Their dismissal of local architecture evokes “a modern future set against a primitive present,” as the historian Frederick Cooper has put it.14 Although the Sipopo Congress Center is said to be symbolic of a future of economic growth, it is realized at the expense of, and to the exclusion of, the citizens of the nation. The foregrounding of the future, however distant, dominates development discourse and is central to the way in which it allows for the continuation of infrastructural lack in the present. The future imagined by the Center suggests its importance in maintaining and legitimizing the state’s involvement with corporate extraction in the present.

Materials of Modernity

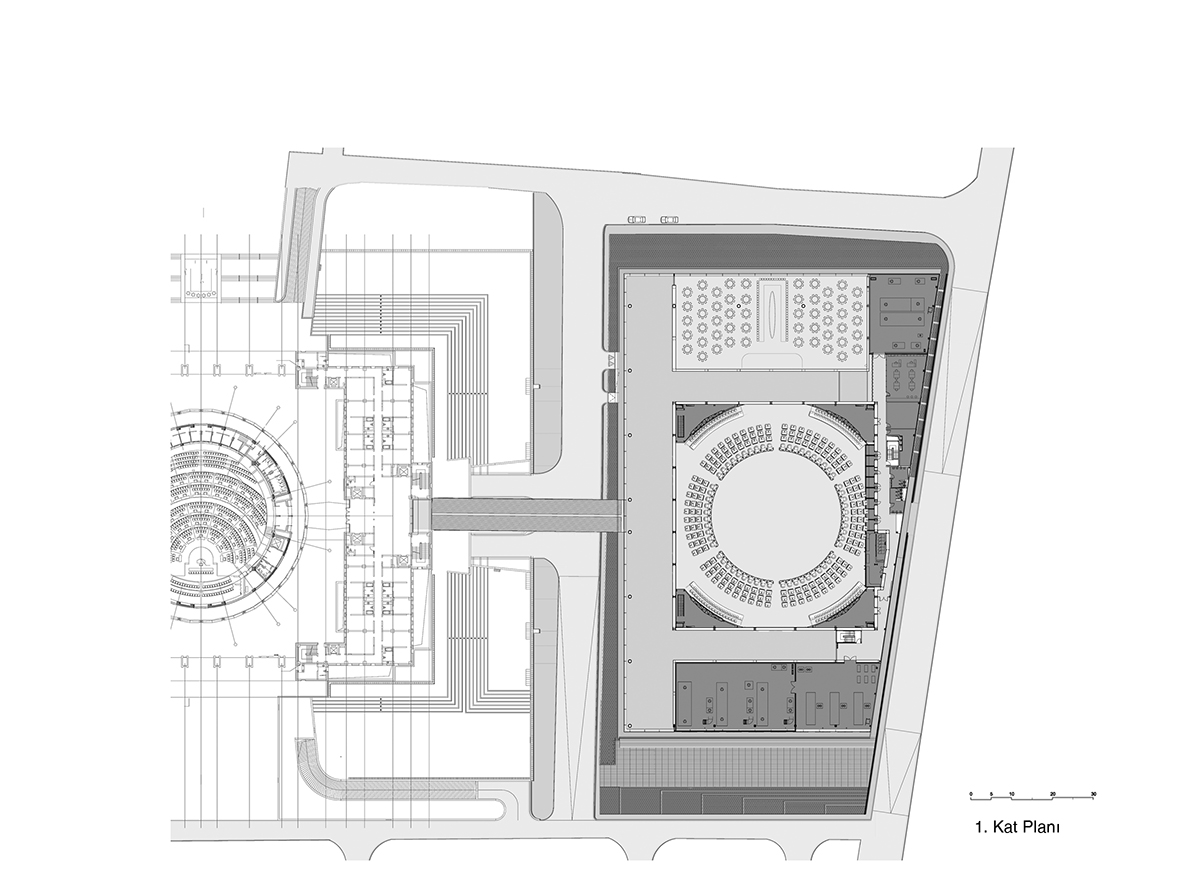

Transparency is deceptive. The firm celebrates its façade as one of “lacy texture” and an “accent of transparency” that balances heat and shade. These descriptions allude to the excessive, elaborate aesthetic that negotiates transparency and distracts from the building’s primary political function. Although the building is transparent from the outside, its main conference hall is not. It is insulated as a “box within a box”—the plans of the Center show two rectangular wall enclosures, forming the main hall and the building, respectively.15 Privacy is hereby designed into the building’s form. The conventional rectangular rooms and the technology concealed within its layered, three dimensionally patterned walls ensure that “confidential talks and important decisions” are carried out in an insulated, detached environment.16 The clear glass of the outer wall pretends to a politics of visibility. As a result, the Sipopo Congress Center, a building meant to facilitate unity through political discussions, not only reproduces an absent relationship with its citizens but does so under the appearance of transparency. And, in fact, this transparency is an inverted one—the inhabitants of the building, representatives of the state and its controlling interests, have a constant and privileged view of the outside while those excluded, the citizens who dwell in the outer environment, risk perpetual monitoring from the inside, should they even attempt to access this purportedly public site. Yet the discourse of modernity allows infrastructural projects to manufacture the “shared goal” of citizens who want to inhabit a modern future.17

The historian James Ferguson has argued that the rhetoric of “development” recognizes the state responsibility to provide services but uses it to extend the state’s reach over its citizens through its implementation of development projects.18 He notes that attention should be paid not only to the end results of development projects but to their “instrument effects”—the ways in which the development of architecture and infrastructure (materially, economically, socially) act as a means to entrench state control.19 The Sipopo Congress Center’s glass enclosure, for example, was consciously chosen as a symbol of modernity, giving it a particular rhetorical role in representing the sovereignty of the state—yet that glass also brings with it a multiplicity of meanings reproduced by this material. If the glass permits for unobstructed views of the ocean and forest, it is also in confrontation with the natural environment, particularly when taking the elaborate metal pattern into account. Brian Larkin has observed how man-made objects, particularly those meant to exhibit the state’s power by controlling the natural world, “become sublime” when they are placed “in relation to other objects.”20 In this case, the presence of the building shifts the focus away from the view and on to itself, becoming a spectacle that makes the Congress Center the main site of observation rather than the natural environment.

This separateness, or a kind of object autonomy amid the tropical landscape of Malabo, is crucial to the structure’s projection of a modern image. Its continuous illumination into the night is allowed by the lights that are “glowing from within” the building.21 This lighting scheme further emphasizes the independence of the building from its surroundings, refusing to be bound to the constraints of time and darkness, a spectacle of perpetual visibility that appears to conquer the environment in the face of modernity. The incongruity of this lighting is heightened by the many gaps of electrification throughout the rest of the island, where many villages still remain off the grid and have become the focus of infrastructural development projects.

Land-Locked: The Contradictions of Development

The Sipopo Congress Center is one among many projects that have been praised as forces of development in Equatorial Guinea. The intended construction of government buildings and a hydroelectric plant in the new capital city of Djibloho, also known as Oyala or Ciudad de la Paz, presents similar notions of developmental modernity, which fundamentally bypass the lived reality of need among the country’s citizens. In 2012, the state began design discussions with Chinese funders for a new hydroelectric plant situated near the Wele River, originally intended to open this year.22 This eight-year timescale is an example of the modes of futurity at stake in the vision of such development projects. The extended time frame allows for the state to delay the responsibilities of the present—providing energy to more remote, rural areas—which, in turn, allows it to extend its reach over its citizens before their “development” can take place.23 Construction in Djibloho might be understood as a product of what James Ferguson has termed an “anti-politics machine”—a way of understanding how the apolitical appearance of development projects participates in the expansion of state power while seeming to depoliticize the status quo allocation of resources.24

Unlike Malabo, Djibloho is a land-locked city, far removed from offshore oil extraction. The shift in focus from Malabo (island territory) to Djibloho (continental territory) indicates the way in which this change allows for an extent of separation between sites of extraction and sites of development in order to maintain a modern image built on resource exploitation. The island, the site of oil extraction that propels development projects, is alienated from the continental nation where these projects are now beginning to be implemented. The relationship between the continental and island space can be seen as a territorial manifestation of the same dynamics between oil extraction and the glass structures. The continental space becomes a site on which to imagine a modern future and a means to exercise political rule while the island, the site of oil extraction, continues to realize projects to maintain economic exploitation. Designating Djibloho as the new capital serves to separate the state’s political and economic functions, allowing the state’s imagined center to disassociate from oil production, its source of political existence. Furthermore, while Obiang has used notions of energy “for all” to legitimize development projects such as the hydroelectric plant, other developments such as The Grand Hotel Djibloho and the Oyala Government Palace that emerged in parallel have exorbitant budgets that disregard inequalities of local circumstances, entrenched by their lavish aesthetics.

As with the Sipopo Congress Center, plans for Djibloho rely on contradictions, on an environmental discourse that constructs particular notions of progress that continues to be put into effect through exploitation. Situated among the dense rainforest, Obiang uses Djibloho’s hydroelectric plant to celebrate notions of “clean energy” suggestive of environmental awareness.25 On the other hand, Equatorial Guinea’s minister of energy was unapologetic about the possibility of exploiting resources to improve the economy and create jobs through oil production.26 These contradictory statements make the discourse of environmental sustainability paradoxical, functioning not only as a means to maintain an image of modernity but also to conceal oil as the source of production and development. Timothy Mitchell’s well-known Carbon Democracy explicates the way in which the extraction of oil requires few workers and how its fluidity enables easy transportation over sea and underground, thereby making its extraction inherently undemocratic. He links this as well to the manipulation of environmental conservation discourse to promote the oil industry. The environment, then, becomes a “set of forces” through which the oil industry can mobilize itself, remaining a persistent player in the emergence of more environmental infrastructure, such as the colossal hydroelectric plant, and distracting attention from oil production by presenting an image of sustainability.27

Legitimacy

“Absence” presents itself in Equatorial Guinea in various ways. The very nature of oil contributes to unequal relations—relations that are made visible through the lack of infrastructure and through “material suffering,” the accumulative absence of basic, everyday necessities.28 Again, oil produces excess and lack that afflicts the majority of residents. Appel has testified to the inadequate access to water, electricity, and health care among local workers in Malabo.29 Comparing these deficiencies to the perpetual electrification of the Sipopo Congress Center, it is possible to see how infrastructural violence is replicated on the “level of everyday practice.” Development projects concentrate the uneven distribution of resources and obscure the inadequacies of civic life. The image of civic life they put forward misidentifies lived reality and fails to address the infrastructural inequalities that undergird it. Since infrastructure is embedded in the everyday, its absences and disparities are central in the subsequent marginalization of the vast needs of citizens.

Sipopo and Djibloho materialize the undemocratic nature of oil. They extend the legacy of modernism in architecture, notorious for dismissing power relations and for breeding social “unevenness.”30 Equatorial Guinea is no exception to these logics: while its per capita wealth is larger than that of Britain, 75 percent of its citizens’ average income is less than one dollar per day.31 This juxtaposition—between the existence and visibility of sites like the congress center and the absence and invisibility of basic necessities—is a materialization of the undemocratic landscape of oil extraction in Malabo. The focus on economic growth as an opportunity for architectural expansion further distracts from the oil driving this expansion in Equatorial Guinea.32

Paradoxically, “illiberal” African governments, exemplified by Obiang’s autocratic rule, have attracted the most investment. “Illiberal” is a term often deployed by the “liberal” West to describe African states that function through undemocratic rule and are often militaristic, such as Angola, another example of an oil-rich country, where unrest continues while simultaneously attracting large foreign corporations. Ferguson explains how this allows oil companies to extract resources without being implicated or appearing as complicit.33 Yet, the government’s continued participation in exploiting capital needs to be legitimized. The total absence of state responsibility or accountability manifests most clearly in the emergence of glass structures. While the country may lack adequate public infrastructures, a condition that would implicate it as an inefficient state, the building of “other” state infrastructures, even those that go unused, serves to give the opposite impression through their modern, glass aesthetics—a state that appears to be actively engaged with its country’s landscape. These “white elephants,” writes Appel, function to abdicate state responsibility.34 In fact, they seem to signal a re-alignment of responsibility: framing not the state but society. Inequalities are subsequently seen as a societal concern where “all members of society are implicated” but “whose effects are ostensibly nobody’s fault” thereby alleviating state responsibility.35

The form of the Sipopo Congress Center embodies this by emphasizing the collective produced by the circular seating within the rectangular rooms—a layout of “concentric layers” that has been repeated by Tabanlιoğlu architects in the Tripoli Convention Center in Libya, similarly said to be a space for progression, exchange, and reconciliation.36 The rigid circulatory pattern and the forced sense of collectivity can be seen as an essential feature of the architecture for autocratic governments such as Libya and Equatorial Guinea, contributing to the materialization and naturalization of displaced state responsibility.

Structures and Systems

The flow of oil sometimes seems to be a secluded system that functions outside geographical, national space while linking isolated points between countries. Since oil extraction works within heavily monitored, “enclaved” spaces, it appears (or wants to appear) as if detached, autonomous from global systems.37 But sites such as the Sipopo Congress Center ground this ostensibly fluid space, housing its capital and providing symbols of the nation’s participation in vectors of globalization. Its focus on the African Union and the outsourcing of its production to Turkish expertise entrenches the centrality of these global relations; the building’s discourse of reconciliation evokes democratic values serves instead a legitimizing function. The disparity between the oil’s concealing relationship with globalization and this site’s explicit interaction with the global indicates the negotiation of narratives required to maintain the systems of capital flow, as these glass structures of “modernity” and “unity” enable both governmental participation in resource exploitation, and architecture firms who would profit from this regime.

The tension between agency and structure is significant in distinguishing the architect’s participation in this process. The necessity of inquiring into the relationship between the architect and the city, where the latter imposes certain constraints, is significant for architectural analysis.38 In the context of Equatorial Guinea, the system of oil extraction has fundamentally shaped the agency of the architecture firm, by enforcing both limitations and opportunities. On the one hand, exorbitant oil profits meant the excessive budget for the Sipopo Congress Center remained undisclosed. However, the firm itself required its own discourses to legitimate its participation in constructing a building for the autocratic Equatorial Guinean state whose rule is synonymous with kleptocracy. In order to do so, the firm said they focused on peace, the African Union, and negotiations.39 The discourses of nature, harmony, and development used to justify their participation indicate the way in which their agency was limited. To this extent, the city as a structure includes the spatial realm of the political and economic that are inseparable from architectural innovations.

Discourses of modernity, futurity, and development enable architects and development planners to produce peace-driven narratives that underpin their participation in oppressive regimes. But as the absence of everyday infrastructural and social necessities that afflict local residents continues to go unrecognized and sites of the future remain unoccupied, the materialization of these visions remains uncertain. At the Sipopo Congress Center, emptiness dwells behind the glass walls, obliging us to question whether it has already become a ruin of the future.40

-

Ian Birrell, “The Strange and Evil World of Equatorial Guinea,” the Guardian, October 23, 2011, link. ↩

-

Hannah Appel, “Walls and White Elephants: Oil Extraction, Responsibility, and Infrastructural Violence in Equatorial Guinea,” Ethnography, vol. 13, no. 4 (December 2012): 454. ↩

-

Appel, “Walls and White Elephants,” 456. ↩

-

I am drawing here particularly on James Ferguson, “Seeing Like an Oil Company: Space, Security, and Global Capital in Neoliberal Africa,” American Anthropologist, vol. 107, no. 3 (September 2005): 379. ↩

-

David Adjaye, quoted in Clifford A. Pearson, “Interview: David Adjaye Revisits Africa,” Architectural Record, vol. 200, no. 8 (August 2012), link. ↩

-

Philip Jodidio, Architecture Now! 9 (Cologne: Taschen, 2013), 430. ↩

-

Mario Gooden, “The Problem with African American Museums,” in the Avery Review, no. 6 (March 2015), link. ↩

-

Gooden, “The Problem with African American Museums.” ↩

-

William Hanley, “Diplomatic Maneuver: A Turkish Firm Combines Natural Forms and Rich Materials in a Meeting Hall for the African Union,” Architectural Record, vol. 200, no. 8 (August 2012): 69. ↩

-

Appel, “Walls and White Elephants,” 447. ↩

-

Hanley, “Diplomatic Maneuver,” 70. ↩

-

Hannah Appel, “Infrastructural Time,” in The Promise of Infrastructure, ed. Nikhil Anand, Hannah Appel, and Akhil Gupta (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 53. ↩

-

Frederick Cooper, “Modernizing Bureaucrats, Backward Africans, and the Development Concept,” in International Development and the Social Sciences: Essays on the History and Politics of Knowledge, ed. Frederick Cooper and Randall Packard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 65. ↩

-

Hanley, “Diplomatic Maneuver,” 70. ↩

-

Christine Schröder, “Kongresszentrum Sipopo in Malabo: Entwurf/Design, Tabanlioglu Architects, TR-Istanbul,” Architektur, Innenarchitektur, Technischer Ausbau 12 (2012): 91. ↩

-

Akhil Gupta, “The Future in Ruins: Thoughts on the Temporality of Infrastructure,” in The Promise of Infrastructure, ed. Nikhil Anand, Hannah Appel, and Akhil Gupta (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 68. ↩

-

James Ferguson, “The Anti-Politics Machine: ‘Development’ and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho,” the Ecologist, vol. 24, no. 1 (1994): 253. ↩

-

Ferguson, “The Anti-Politics Machine,” 255. ↩

-

Brian Larkin, Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 35. The “sublime” is used to refer to phenomena that are beyond comprehension. Infrastructures such as bridges and railways portrayed the sublime through man-made objects, rather than the natural, during the colonial era. The sublime is connected to an exhibition of power where “resistance is useless.” Larkin, Signal and Noise, 36. ↩

-

Jodidio, Architecture Now! 9, 434. ↩

-

PR Newswire, “Equatorial Guinea Inaugurates New High-Capacity Power Plant in Djibloho,” PR Newswire US, October 12, 2012. ↩

-

Yang Yi, “Chinese-Built Hydropower Project to Boost Equatorial Guinea Economy: President,” Xinhuanet, March 25, 2020, link. ↩

-

Ferguson, “The Anti-Politics Machine,” 268. ↩

-

Africa Oil and Power, “Equatorial Guinea: Djibloho Hydropower Plant Completed,” December 3, 2018, link. ↩

-

Libby George and Shadia Nasralla, “No Apologies: Africans Say Their Need for Oil Cash Outweighs Climate Concerns,” Reuters, November 8, 2019, link. ↩

-

Timothy Mitchell, “Carbon Democracy,” Economy and Society, vol. 38, no. 3 (August 2009): 420. ↩

-

O’Neill and Rodgers, “Infrastructural Violence: Introduction to the Special Issue,” Ethnography, vol. 13, no. 4 (December 2012): 405. ↩

-

Hannah Appel, “Offshore Work: Oil, Modularity, and the How of Capitalism in Equatorial Guinea,” American Ethnologist, vol. 39, no. 4 (November 2012): 704. ↩

-

Noëleen Frances Murray, “Architectural Modernism and Apartheid Modernity in South Africa: A Critical Inquiry into the Work of Architect and Urban Designer Roelof Uytenbogaardt, 1960–2009,” PhD dissertation, University of Cape Town, 2010, 46. ↩

-

Birrell, “The Strange and Evil World of Equatorial Guinea.” ↩

-

Cathleen McGuigan, “Africa Today and Tomorrow,” Architectural Record, vol. 200, no. 8 (August 2012): 14. ↩

-

Ferguson, “Seeing Like an Oil Company,” 380. ↩

-

Appel, “Walls and White Elephants,” 454. ↩

-

O’Neill and Rodgers, “Infrastructural Violence,” 404. ↩

-

Blanca Lleó, “Tradition and Modernity,” the Architectural Review, vol. 235, no. 1406 (April 2014): 20. ↩

-

Ferguson, “Seeing Like an Oil Company,” 377–379. ↩

-

Murray, “Architectural Modernism and Apartheid Modernity in South Africa,” 8. ↩

-

Murray, “Architectural Modernism and Apartheid Modernity in South Africa,” 68. ↩

-

Gupta refers to abandoned infrastructure built for spectacle as “ruins” and the “afterlife” of infrastructure. Gupta, “The Future in Ruins,” 69. ↩

Sameeah Ahmed-Arai is a student at the University of Cape Town, majoring in English, history, and French. She has a special interest in spatial histories.