Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art features works by seven emerging Latinx artists based in the United States and Puerto Rico. By inviting artists whose work addresses “indigenous and vernacular notions of construction, land, space, and cosmology,” it shifts what is acknowledged as architecture within predominant Western institutions—the Whitney Museum of American Art chief among them.1 The exhibition is the project of Marcela Guerrero, her first for the Whitney since she was hired as an associate curator in April of 2017 to focus explicitly on Latinx art.2 Guerrero defines Latinx as “a gender-neutral term for people of Latin American heritage,” but the identifier draws polarized reactions.3 It is sometimes seen as dismissive of gender identity and expression. At the same time, many scholars are interested in the potential of the term’s plurality and ambiguity to invite new perspectives and methods to define identity at the intersection of multiple systems of oppression and power.4 With the added emphasis on indigeneity, the exhibition itself is structured with as much complexity as the X in Latinx: It asks the viewer to engage with identity as fluid, uncertain, and contradictory while posing Latinx as a decolonial movement and aesthetic, a linguistic provocation, a people, a politic.

Over the past few years, indigenous activism and ways of thinking have been featured more prominently in popular media outlets and presented as models for securing our shared ecological future. The broader public has much to gain from this fight, not the least of which includes mitigating or slowing the impacts of climate change (a fact the United Nations never ceases to leverage).5 But Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay refreshingly refuses to mobilize indigeneity to serve a universal notion of human rights or to seek mere approval. This show instead forces the broader public to grapple with an indigenous identity as it produces, and is produced by, art and architecture. It puts the topics in relation to an institutional tradition that has relegated this work to the annals of “Pre-Columbian” art history. Even a cursory review of the architectural terms in the exhibition’s title reveals the difficulty of their translation into English and Spanish (“Pacha denotes universe, time, space, nature, or world; llaqta signifies place, country, community, or town; and wasichay means to build or to construct a house”).6 The complexity of the terms demonstrates that indigenous architecture exists beyond the forms previously identified (for example, vernacular housing). It also exists as space-making method, technology, and effect, and achieves architectural goals—the creation of places, times, and publics. The underrepresentation of these practices has kept indigenous architecture at arm’s length and has thus prohibited the inclusion of its architects within the canon.

Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay takes on the problematics of indigenous representation, asking the viewer to ruminate on identity and art at the intersection of indigeneity and migration. Scholars from the emerging field of Critical Latinx Indigeneities, such as Maylei Blackwell, Floridalma Boj Lopez, and Luis Urrieta Jr. point out that the left’s recent emphasis on the United States as a nation of immigrants risks erasure of one of the country’s most significant truths—it is founded on violence toward indigenous peoples and indigenous knowledge of land and life. This violence, across the Americas, produces the conditions that some of the work in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay speaks to (cultural appropriation, an exclusive/elusive American identity, migration, and statelessness). While much of the art in the exhibition is informed by indigenous practices or heritage, not all of the artists in the show identify as indigenous, confronting audiences with the colonial history that separates (or conjoins) indigenous heritage and with the problems of claiming a “national” identity that has been altered by state violence across generations.7

In a moment of increased “national security” and xenophobia toward immigrants, particularly those from Latin America, Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay’s presence within the Whitney Museum of American art formally recognizes works by Latinx artists informed by indigenous cultural practices, as significant pieces of American cultural identity. The works, in dialogue with highly iconic pieces of American architecture, are part of a too-slowly evolving acknowledgment of Latin American and indigenous art as essential to contemporary American experience. As Livia Benjamin Corona, one of the artists in the show, said, “It’s like all of us knew, and the museum just found out... I feel like I’ve always been American.”8

To make these topics visible, Guerrero has shifted the structure of exhibition practice, selecting several artists who work directly with indigenous communities, and with indigenous-identified artists and artisans, including them in events that expand the typical educational infrastructure of the museum.

By titling the show in Quechua, by offering tours, placard translations, and several unique events in both English and Spanish (including a mini-opera designed by Guadalupe Maravilla), she draws a broader audience to the museum. Guerrero also operates as an architect herself, using the design and construction of the exhibition to alter the predominantly visual language of the museum and its typical hierarchies of display. Rather than leaving museum works as objects to be viewed, she collaborates with artists to introduce moments of tactility within the overall experience (for example, floor tiles of gold leaf and linoleum in Ronny Quevedo’s work accumulate scratches as visitors walk over them). She also works with artist Jorge González to introduce objects of use, like furniture and books, to deconstruct the concept of an art artifact as something inaccessible, unusable, and precious.

Together, the work included addresses architecture as body, drawing, event, building, and sociocultural technology. Through these pieces and methods, the show creates an image of and space for diasporic indigeneity and offers possibilities for an American identity not defined by citizenship alone. Fifty-three years after “Architecture without Architects,” Rudolfsky’s controversial exhibition, the designers and curators of many recent shows featuring indigenous architecture have demonstrated that some of the world’s most powerful architectural institutions are capable of naming indigenous architects. But these exhibitions still speak to a narrow architectural audience.9 Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay opens the contemporary art landscape to architecture made from a distinctly embodied perspective. Shows like this one might finally dislodge the long-standing relegation of indigenous art and architecture to museum spaces that have historically rendered them anthropological artifacts, and not part of a common visual culture.

Architectural Bodies

Artists Clarissa Tossin and Guadalupe Maravilla speak to the body as an architecture—as a space that’s constructed and that constructs, and one that put pressure on modernist spatial narratives. Maravilla’s work shows that an American architecture of territory is not just constructed by the settler home—the single-family unit built to be populated by objects from the Sears Roebuck catalog. It is also built by the occupation of the land in other ways. In Maravilla’s case this is built by the immigrant’s search for home across borders, and in Tossin’s case by the body’s occupation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s appropriated Mayan architecture.

Brazilian-born, Los Angeles-based Tossin’s pieces are the first works encountered in the show. A series of sculptures, including Yaxchilán Lintel 25 (feathered serpent) and Ch’u Mayaa (Mayan Blue), a video piece, appear together for the first time, allowing Tossin’s work to build, rather than merely inhabit, the space of the museum.10 Fragments of Mayan ornament protrude alongside hands and hair hewn in a corporal terra-cotta. Recast by her own hand, Tossin impresses upon the visitor the historic use and appropriation of Mayan styles by the sculptor Francisco Cornejo in Los Angeles’s iconic Mayan Theatre and by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House.

In Yaxchilán Lintel 25, Tossin’s hands and feet are cast in terra-cotta and support architectural garments made of silicone molded from Cornejo’s theater facade.11 Tossin hangs iconic corpses of her construction side-by-side: A braid of synthetic hair, adorned with faux-feathers, and the elastic facade, hang emptied of material depth, but centuries of Mayan intellectual and physical labor can also be read within these copies-of-a-copy. These works succeed in constituting a new body—one that speaks of an identity formed from, in resistance to, and despite its appropriation by architecture.

The theater has a storied history as the home for various scopophilic fantasies; built in the Mayan Revival style in the 1920s, during the movie palace heyday, audiences would flock to experience something otherworldly, exotic, desirable. The building later became a center for Spanish-language films, a porn theater, and, most recently, a nightclub. The architectural body and Tossin’s own body are here mutually imbricated as objects of modernist desire and projection. The skins of both material entities are sites of (il)legibility and (mis)interpretation, which contend with modernism’s obsessions with primitivism.12

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House—the setting for the Ch’u Mayaa film is a site of similar fascination, one that also contributes to our shared legacy of racial constructions. In Ch’u Mayaa, the house is rendered as both backdrop and occupied body, captured in Crystal Sepúlveda’s performance against, around, and within it. It’s a fetishist’s architectural creation: Apparent here is the modernist desire for a second skin (the desire to construct another body, an other body against which to identify one’s own subjectivity). And it is this desiring subject that is brilliantly upstaged by Sepúlveda’s performance of multilayered identity taking cues from Mayan ontology.

The epistemology of the skin in Mayan culture, not unlike some feminist formulations of body, problematizes Western notions of a stable body—as either human or animal, dead or alive, woman or man, skin or corpse. Mayan culture traditionally sees bodies, skins, as vessels constructed by an inner soul—one that may, through its own desires and agency, transform its appearance and capacity through actions like drinking, eating, dancing. The act of putting on a mask is not merely a visual act of costuming or concealing the body; it is a way of metaphysically transforming the self—in Sepúlveda’s case borrowing the body of the jaguar to channel its particular strengths.13 Together, the leotard, dress, and tennis shoes—emblems of speed—are worn in ways that honor another being to generate power. Wearing the skin of the jaguar, itself dressed in human clothing, Sepúlveda is both/or, depending on your view.

Wright’s power to control the image of a Mayan Revival Architecture, and to depict it as a private home for a wealthy white owner through the circulation of images of the Hollyhock House, is wrested by Tossin and Sepúlveda’s designed and imaged occupation.14 Sepúlveda expertly harnesses video as a medium to reproduce her own body as architecture, using it to reprogram the private house as public space. It is the space between our own viewing bodies and her multiplicitous selves, depicted on-screen, that enacts this transformation.15 In between the masculine mode of self-creation and the feminine mode of reproduction, Sepúlveda reconstitutes the architecture of the public in the home not built for her, in the white-walled gallery, and in the architectural discourse that continues to celebrate Wright and his spolia.

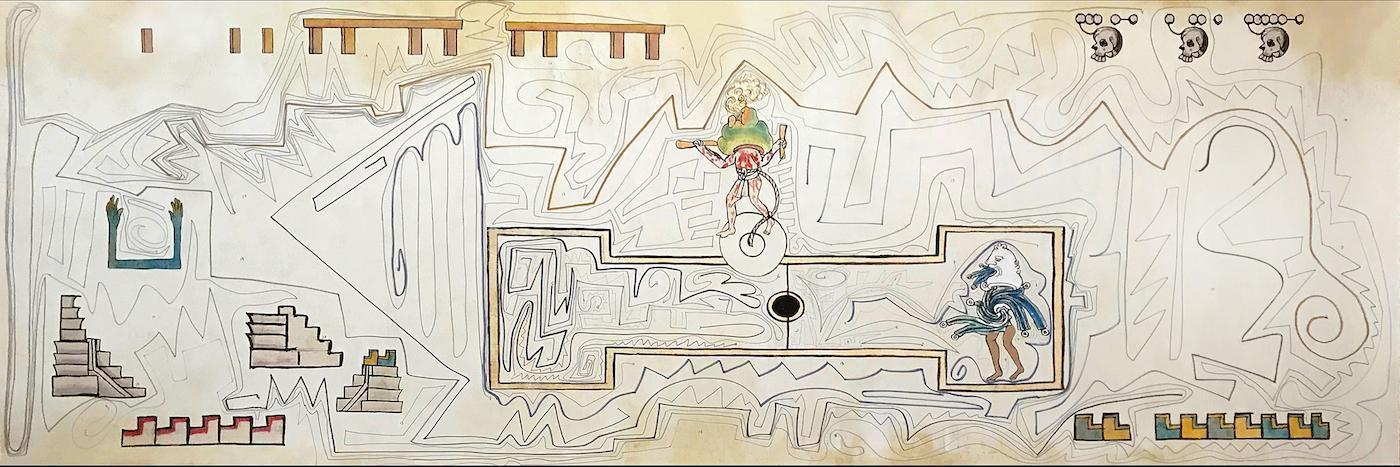

Maravilla’s work similarly invokes an architecture of the body, whose movements, possible and denied, are represented at the elastic scale of the map (it’s handheld, hand-drawn but traverses territories, pasts, and futures). Using photocopies of images from a Nahuatl codex made during the Spanish conquest, he creates a canvas upon which he draws lines that represent his, and other immigrants’ navigation of unknown land. His pieces are made in collaboration with undocumented immigrants to the United States, by playing Tripa Chuca (“Dirty Guts”). Each player starts at a given point, taking turns making lines on a page, careful not to cross the others’ lines, as they continue. Here, a map is a line made by a body, one navigating a fragment from a codex or an unknown terrain, one set within a landscape that’s as much psychological as physical. The site is here neither cleared nor constructed, but navigated, known only through first-person encounter. This is space-making in an era of statelessness, in which space and place are often made in search of home rather than in its permanence. The graphite lines are also drawn directly onto the museum’s walls, turning the corner of the exhibition wall as their language changes from fluid, river-like to a hard, bordering line.

Consumerism and Souvenir Culture

Themes of consumerism introduced by Tossin’s synthetic sculptures are further explored in the work of Ronny Quevedo and Claudia Peña Salinas. Ronny Quevedo’s prints and sculptures speak to the legacy of the Aztec game Ulama, seen in sports like basketball and soccer whose development has typically been associated with Western cultures.16 Quevedo’s Errant Globe is displayed on a pedestal that recalls Mayan architectural forms and references the rubber ball used in Ulama. In the sixteenth century, rubber extraction in the Amazon fueled violence toward indigenous peoples and supported the colonial project. Here, the rubber’s solidity and uniform color obscure the typical elements of the globe as a tool of colonization: the rational grid and its positioning of the equatorial line demarcating global north and south. The globe’s pedestal, designed by Guerrero, also references the monument at Mitad del Mundo (middle of the earth), a primary tourist site in the Ecuadorian highlands, and in so doing, invokes a consumable geography. The Mitad del Mundo is not, in fact, located on the equator, but the authenticity of the location seems to be irrelevant to tourists interested in consuming this experience.

Claudia Peña Salinas’s work also addresses the misrepresentation of traditional cultural sites and artifacts as they are reproduced in multiple forms as souvenirs. Her sculptures, videos, and prints explore the displacement of a sculpture of Tláloc, the Aztec deity representing rain, to the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, where it was incorrectly identified as a male god.17 In its displacement, a Western view of gender was imposed onto the figure—the original stone was moved from adjacent murals depicting the God with feminine and masculine characteristics. The video Tlachacan, juxtaposes many recreations of the statue, working as a kind of anti-monument. Peña Salinas’s work occupies a room that she’s fashioned as a Tlalocán, “the mythical paradise known to the Aztecs and ruled by Tláloc and his consort the water goddess Chalchiuhtlicue.”18 The space re-contextualizes the readings of Tláloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, depicted on enlarged postcards printed on metal. She uses this environment to support a reading of the deities that’s more aligned with their original meanings so that the power of their ambiguity is no longer eroded.

Anti-Monumentality

Turning to the urban scale, william cordova’s work also confronts dislocation. cordova has several works on display in the exhibition, but his largest, huaca (sacred geometries), was specifically commissioned for this show. The piece combines the architectural language of Huaca Huantile—a pre-Incan Ichma temple built in what is currently Lima, Peru—with that of the structures built by dispossessed families occupying the temple before it was declared a heritage site. huaca (sacred geometries) is a commentary on the role of the state in the preservation of heritage. In this case, the state uses the heritage designation to preserve a piece of architecture, ironically displacing people of the same identity the decision claims to support.

From the eighth floor of the Whitney, visitors can look down on huaca (sacred geometries) to see the “Big Dipper” formation that it creates. Called the “Big Gourd” by indigenous people of the Americas, it was used as a navigational device by slaves in the United States to flee north during the Civil War. cordova describes the piece as a “non-monument”: it doesn’t invoke any singular heroic figure or nationalistic event or heritage. Rather, it references an ongoing journey, one with roots in multilocal, concurrent histories.

The structure operates as a “non-monument” constructed atop the new Whitney, a building tasked with presenting a new image of American identity and of the twenty-first century museum. Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay harnesses the building’s reflections and views to the city to layer images of dispossession. huaca (sacred geometries) is made against the Manhattan skyline, an expression of the raw power of real-estate, as it rests on unceded Lenape lands.1920

Labor and Architecture

An anti-monumentality also pervades Livia Corona Benjamin’s projects, which deal with the repurposing of thousands of grain silos built in Mexico through CONASUPO from 1965 to 1999.21 Nearly four thousand silos were built by farmers following the architectural drawings of Pedro Ramírez Vázquez. The silos appeared in newspaper articles and on the lands of thousands aspiring to a more stable life, becoming an architectural symbol of the capacity of agriculture to transform national GDP through individual efforts. In the exhibition, a series of diptychs featuring a photograph and floor plan for several of the silos illustrates a possible (or real, a point on which the artist has been notoriously silent) repurposing of the space, again use an architectural document to change the way we see the programmatic and cultural relevance of the structures. Additionally, filmed interviews revisit the advent of NAFTA and a change of government, which ended the CONASUPO project, subsuming a national image painted by individual labor with one of international trade.

The theme of labor extends beyond Benjamin’s work to the very context of the gallery. Artist Jorge González has refigured the distribution of capital from the museum to indigenous communities in Puerto Rico by hiring artisans to teach him their craft, to work with him to construct didactic exhibits, and to present workshops at the Whitney. Ayacavo Guarocoel (shown below) and the Banquetas Chéveres (Chéveres Stools), for example, were made collaboratively with wood-turner Joe Hernández and hammock weavers Aurora and Luz Pérez in Puerto Rico and brought to the museum. 22 23 Two Taíno amulets dating from 1200 to 1500 are displayed on walls beside a library brought by González. Not unlike the stone sculpture of Tláloc, the amulets have been moved to a colonial institution, but the impact of their presence in this context is very different. Here, they can be seen as contemporary works: their unearthing in Puerto Rico was a part of connecting current inhabitants with a Taíno cultural history and identity previously thought to no longer exist.

Educational Infrastructure and Programming

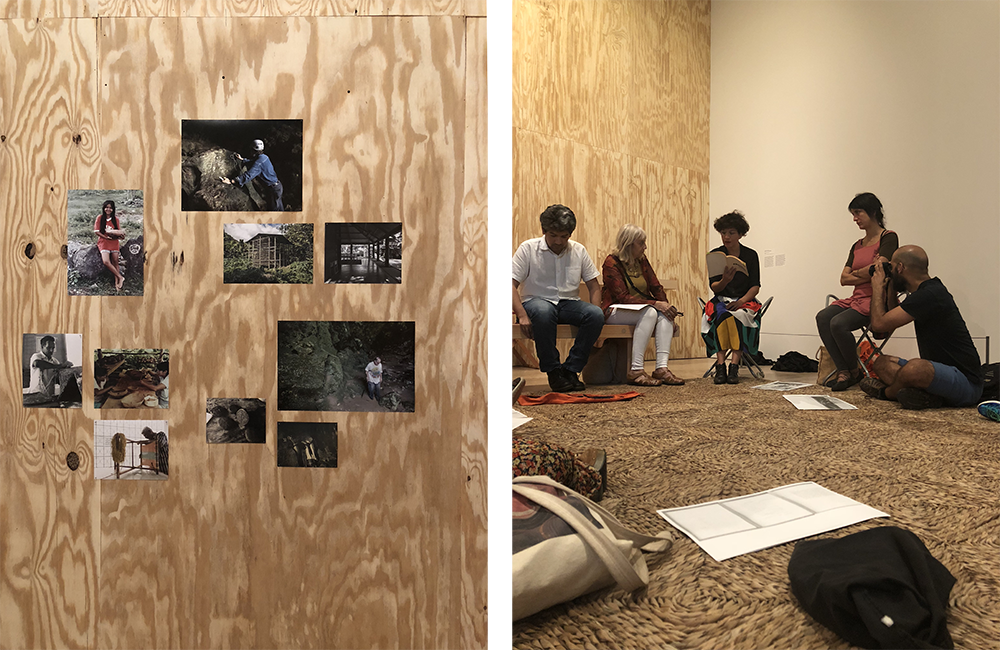

González has long been interested in art’s ability to generate community and in acknowledging artisans as educators. He brings his experience as the founder of the Escuela de Oficios, a mobile trade show that hosts events including conversations, workshops, and exhibitions, to the Whitney to shape its educational programs, including a three-part series titled “Readings under the Cohoba Tree.”24 The event creates an important precedent: it’s one of the first to hold a reading within the space of the art itself, reflecting an attitude that prioritizes the creation of community over the preciousness of the art. Sitting atop a rug woven from enea within the plywood-finished space, next to works built and curated by González, attendees listened to texts read in English and Spanish. Most compelling was the event’s preoccupation with architectural pedagogy: readings from foundational documents of the “Open City” contributed an idea of an architecture “meant to be written and performed in the land, creating a new conceptual foundation of the Americas.”25 The night ended with participants tied together to make a collective serpent, playing one of the games from the Torneos, activities played at the School of Architecture of the Catholic University of Valparaíso. Together, they snaked around the cordova piece, stepping on the concrete tiles of the Whitney.26

Through the creation of these kinds of events, Guerrero acknowledges the museum as more than a site of representation. She, alongside González, asserts and manipulates its existence along lines of exchange: financial economies and affective citizenship are reconstituted by the movement, visibility, and interpretation of artifacts like the Taíno amulets, the enea rug, and the Banquetas Chéveres within a contemporary art museum.

The Whitney has, for the most part, successfully engaged the conceptual and institutional complexities called for by the intersectional politics of Latinx: it’s hired a strong curator, seen that its profits eventually touch the hands of the communities it claims to represent, conveyed ontological and epistemological perspectives robustly, and acted on the appropriating discourses of American art and architectural history through programming and didactic material. These programmatic shifts spoke to a broader audience, but the Whitney’s scant marketing of Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay did not do justice to the work on display. Moreover, the museum failed to sufficiently adapt its docent education program for the show, which could have helped to expand the voices interpreting its content.27 However, additional Spanish-language tours were given by a highly educated and paid guide, an approach that should continue for all exhibitions.

Most disappointing is the absence of a museum catalog. Without it, the documents that will constitute the historical legacy of the show are limited to mostly ephemera: photographs, a playlist, wall text, interviews, and of course the art itself. While the catalog may very well be a stodgy document when compared with the innovative educational formats the show has developed, it is still currently one of the primary artifacts of exhibition canonization. The museum should be committed to creating this document regardless of other programs offered.

Right: “Under the Cohoba Tree,” a three-part performance series organized by González alongside Guerrero and the Whitney’s Department of Performance Studies. For the event on September 15, 2018, González, and artists Felipe Mujica, Francisca Benitez, and Nieves Saah performed readings of texts echoing exhibition themes. This event was led by Mujica. Photograph by the author.

Nevertheless, the exhibition speaks to, and about, a generation of Latinx artists who are for the first time able to articulate identity in this institutional frame. The Whitney’s definition of “American art” is significantly expanded through the inclusion of works by Puerto Rican artists like González, or by the work created by Maravilla’s collaboration with undocumented immigrants. However, the show as written—by critics and in the wall text—defers to nationality in a way that occludes other intersectional identifiers such as queer and indigenous identity, which to some constitute the radical politics of the broader Latinx movement. This preoccupation, for better or worse, leaves the exploration of more complex forms of belonging to the work itself.

Shows that curate based on shared identity must often reconcile the depth of the work presented with a breadth of work that can attest to a movement. In the process, the perspective of an individual artist is subsumed by a framing that appeals to a precise definition, a present moment or a future that regards this work as history. It’s a persistent question: how to mobilize identity without smoothing over the intricacy of personal lives and relations and without erasing the points of overlap and contradiction. Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay generally does this well by simply allowing the work to speak to an expanded architectural definition: architecture is represented as a strategy of reclamation, as technology rather than formal expression, as a space of the body, and as made from an embodied perspective. A pervasive anti-monumentality connects the works—referencing the symbolic and constant construction of space as a negotiation by multiple actors.

While the show is failed by the lack of catalog and sufficient educational infrastructure for its docents, it’s shored up in other ways not so naturalized to the museum. Artists from a broader community are supported; tours are offered in Spanish; work titles are written in Nahuatl, Quechua, and Arawak; and finances are folded into the community through networks of intellectual and physical labor. This show opens the door for a meaningful shift in the institution, its discourses, and its relationship to activism. Guerrero and her collaborators make space for this transition.

-

“Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art,” Whitney Museum of American Art, link. ↩

-

With Alana Hernandez, curatorial project assistant. ↩

-

Marcela Guerrero, “Conceptual Blueprints: Artistic Approaches to Indigenous Architecture,” Whitney Museum of American Art, link. ↩

-

See for instance, Maylei Blackwell, Floridalma Boj Lopez, and Luis Urrieta’s writings on Critical Latinx Indigeneities in “Special Issue: Critical Latinx Indigeneities,” Latino Studies, vol.15, no. 2 (2017): 127; or Claudia Milian’s writing on LatinX identity and the refusal of gender binaries in “Extremely Latin, XOXO: Notes on LatinX,” Cultural Dynamics, vol. 29, no. 3 (2017): 127. ↩

-

The arguments leverage an essentialized identity, stating that indigenous people are “stewards of the land,” have specialized knowledge of how to take care of it, and will preserve it on the world’s behalf. ↩

-

“The three words in the exhibition’s title are Quechua, the Indigenous language most spoken in the Americas. Each holds more than one meaning: pacha denotes universe, time, space, nature, or world; llaqta signifies place, country, community, or town; and wasichay means to build or to construct a house. Influenced by the richness of these concepts, the artworks explore the conceptual frameworks inherited from, and also still alive in, Indigenous groups in Mexico and South America that include the Quechua, Aymara, Maya, Aztec, and Taíno, among others.” From “Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art,” Whitney Museum of American Art, link. ↩

-

In the essay “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color,” Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw describes the organization of women to fight against domestic violence that affects them as a class. This politicization of identity allowed them to “[recognize] as social and systemic what was formerly perceived as isolated and individual [and] has also characterized the identity politics of people of color and gays and lesbians, among others. For all these groups, identity-based politics has been a source of strength, community, and intellectual development.” Yet, this organization also “frequently conflates or ignores intra group differences.” ↩

-

I use American to refer to the Whitney’s mission statement, but I acknowledge the problematics of the term throughout the museum’s history: from its erasure of South American identity, or non-US North American identity, or Puerto Rican identity, among others. The museum’s definition of American does not currently reflect national definitions and the awarding of American citizenship. However, under Thomas N. Armstrong III’s directorship, from 1974 to 1990, the museum only allowed works to be displayed by artists with American citizenship or green cards, even going so far as to de-accession works made by artists who were not citizens. Carol Vogel, “The Whitney Museum, Soon to Open Its New Home, Searches for American Identity,” the New York Times, March 29, 2015, link. ↩

-

See Unceded—an exhibition of work by indigenous architects for the Canadian Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Biennale; Disappearing Legacies: The World as Forest, a show by Anna-Sophie Springer and Etienne Turpin that offers multiple models of world-making against colonial natural histories; or the <i>Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA</i> initiative that funded over seventy projects on Latin American, Latinx, and Chicanx art. See Also Robin Pogrebin, “Museums Turn Their Focus to U.S. Artists of Latin Descent,” the New York Times, April 24, 2018, link. ↩

-

Yaxchilán Lintel 25 is shown alongside A cycle of time we don’t understand (reversed, invented, and rearranged); A two-headed serpent held in the arms of human beings, or, Ticket Window; xojowisaj ja (to make the building dance); Ha’ K’in Xook, from Piedras Negras to Hill Street. ↩

-

George Stein, “Old Mayan Theater May Retrieve Glory,” the Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1989, link. ↩

-

“When it comes to a phenomenon like Modernist Primitivism, what continues to invite reading is therefore not colonial ideology’s repressed content but its expressiveness. What continues to hold our gazes and captivate our minds are those disquieting moments of contamination when reification and recognition fuse, when conditions of subjecthood and objecthood merge, when the fetishist savors his or her own vertiginous intimacy with the dreamed object, and vice versa.” From Anne Cheng, Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 14. ↩

-

Eduardo Viveiros De Castro, “Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 4, no. 3 (September 1998): 469–488. ↩

-

“Wright wanted to invent an indigenous American architecture.” Donald Hoffmann, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House: The Illustrated Story of an Architectural Masterpiece (New York: Dover, 1992), link. ↩

-

“As much as we must insist on there being material conditions for public assembly and public speech, we have also to ask how it is that assembly and speech reconfigure the materiality of public space and produce, or reproduce, the public character of that material environment.” From Judith Butler, “Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street,” in Sensible Politics: The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism, eds. Meg McLagan and Yates McKee (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 117. ↩

-

From Nahuatl. ↩

-

Elsa C. Mandell, “A New Analysis of the Gender Attribution of the ‘Great Goddess’ Of Teotihuacan,” Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 26, no. 1 (2015): 29–49, link. ↩

-

See the description of Claudia Peña Salinas’s work on the exhibition website, link. ↩

-

“Although people have always taken for granted that the Whitney is a museum of American art, we’re trying to signal in a concrete way that who an American artist is has always been open to question,” said Scott Rothkopf, a Whitney curator and its associate director of programs. “Besides, the United States is a country of immigrants, and immigration is one of the most pressing topics in the world today.” From Vogel, “The Whitney Museum, Soon to Open Its New Home, Searches for American Identity,” link. ↩

-

See this resource for more information on indigenous territories, languages, and treaties: link. ↩

-

Compañía Nacional de Subsistencias Populares. ↩

-

As the exhibition wall text explains, González, “took the work’s title from a story written in Fray Ramón Pané’s An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians (1948), the first book written about the Taínos after the Spanish arrived in Hispaniola in 1494; Ayacavo Guaracoal translates from the Arawak as ‘let’s meet our grandfather.’” ↩

-

From the author’s interview with González. ↩

-

From the author’s interview with the artist: As González described, “‘Readings Under the Cohoba’ featured one reading each month of the exhibition, directed by three different collaborators; Francisca Benítez, Monica Rodríguez, and Felipe Mujica. Readings were also organized weekly, in a casual manner among friends, museum’s staff, and visitors.” ↩

-

The second part of the evening was inspired by Jugador como pelota, pelota como cancha, which described Torneos (Tournaments), games played at the School of Architecture of the Catholic University of Valparaíso devised by Manuel Casanueva. ↩

-

Much has been written contesting the role of the docent in communicating art’s value and providing knowledge to the public. Docents at the Whitney spend a single week researching and writing a paper about the show, have a collective meeting with the curator reviewing material, and then set off to give tours. The use of predominantly self-educated volunteers becomes increasingly problematic at the intersection of class and race, as those able to volunteer typically come from a position of privilege. This type of inherent imbalance could be addressed with adequate compensation for docents and the expansion of docent educational frameworks. This becomes even more important when the artworks on display are less likely to have already been written into the canon, meaning docents cannot easily self-educate by researching existing literature. ↩