Nairobi is synonymous with chaos. Ask anyone in Nairobi, and they will tell you, “We lack planning,” as if to say that in the absence of a plan anything goes, or even, conversely, that a document can dictate the nature of city life. In most people’s minds, plan-making is by its own virtue self-fulfilling (if it is planned, it will be built).

A series of architectural renderings allow for speculation as to the spatial and political implications of Winners’ Chapel, an unplanned fifteen-thousand-seater megachurch in Nairobi. The renderings, which were published on the church’s Facebook page and which depict a new multifunctional hall, are an exercise in “planning” but perhaps not in the conventional sense. Instead, Winners’ Chapel is an illustration of how seductive images and a new form of charismatic actors have robbed the state of its role as mediator of urban development. In Nairobi, ecclesiastical transformations have led to a new visioning of the future that is announced, debated, and circulated through the internet. This speaks to the city’s particular form of political development. Nairobi’s elites have attempted to construct a common definition of “the public” since the city was founded just over a century ago.1 In the absence of this collective sense of identity, the “public” has come to be embodied spatially (rather than politically) in singular, compelling variations: the covered shopping center, the church, the government square, the megachurch. These spaces are compelling because they traffic in the myth that Nairobi can be remade through sheer willpower. The exact makeup of these transformative actors, however, remains contested. Is urban transformation in Nairobi captured by powerful elites (religious or otherwise), or is it the result of the collective will of citizens, bound by a singular purpose?

A latecomer to the urban dynamic of Nairobi, the megachurch arrived via Lagos after a long gestation in the American Midwest. The largest, Winners’ Chapel International, sits on a contested strip of land along Mombasa Road—a major artery running between the city, the principal international airport, and the Indian Ocean.2 3 4 The “international” in its name is intentional. Winners’ Chapels can be found throughout Africa, Europe, Australia, and North America.5 The charismatic Bishop David Oyedepo heads the church and flies frequently from the “mother church” in Ogun State to daughter churches by private jet, a fact that does not escape his congregants. The bishop’s ascendancy from the ranks of the decimated middle class in post-oil boom Nigerian in the early 1980s to God’s anointed servant is part of the church’s dogma.6 Before his glorious revelation, the bishop worked as a government architect—a fact that casts the church’s architectural choices in a new light.

Architecturally, Winners’ Chapel Nairobi is unremarkable except for its scale. The roof is made of corrugated iron sheets, a material that is familiar in Kenya but when rendered at this scale takes on a nefarious dimension. These are not the clay tiles favored by the mock-Tudor Anglican cathedral in downtown Nairobi, long since the bastion of class and ethnic supremacy. The Nairobi incarnation of the franchise follows a dramatic architectural pattern. Here the entrance is exaggerated, the columns framing the main doors clearly too small and out of scale for its bulky roof. On either side of the main church doors, mirrored glazing dazzles in the Sunday morning heat, baking the arriving congregation. The church is laid out in a hexagon, a fact that has fueled all manner of internet conspiracies.7 In fact, half of Nairobi is torn between deep suspicion of the church’s ambition (fueled by xenophobia and the melodrama of Nollywood thrillers) and attraction to the magnetic charisma of a roving cast of male preachers.

Despite its generic gaudiness, the church is a masterwork of performance—a delicate choreography between spectator, pastor, and gathered public. It is the transformation of what is, in effect, an aircraft hangar with a magisterial façade, into a site of dutiful co-option. This transformation is possible because of the symbolism encoded not in the building but in the gathering of bodies that takes place within it. Writing on the work of the architect David Adjaye, the curator Okwui Enwezor used the phrase “gestures of affiliation” to refer to Adjaye’s civic buildings—specifically the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., and the proposed Cape Coast Slavery Museum in Ghana.8 They are “gestures” in part because both buildings are twins, spanning space, time, and the wounds of history, and in part because they recontextualize the public’s relationship to buildings weighed down by symbolic value. They are themselves the climax (because they are allowed to exist at all) and the counterpoint (because they do not explain themselves) to a narrative of forgotten history. Unlike those buildings, Winners’ Chapel gestures wildly in Nairobi’s landscape like a corporate logo. It is the symbol the city needs because acute desire can be expressed here, with thousands of simultaneous “amens.” In effect, the church becomes an arena for the transformation of individual desire into a collective and perhaps even political force for urban transformation.

In 2016, Winners’ Chapel announced the “Faith Theatre Project,” a new multipurpose venue that is assumed to complement the mammoth sanctuary building. The architectural renders posted on the church’s Facebook page are illuminating because of the way they galvanize desire and project these desires to the world. Whether the project—which is more shopping mall than faith venue—is built as rendered, or even built at all, is beside the point. Reading the comments section alongside the renders, it is clear that for the congregation of Winners’ Chapel, erecting this mammoth venue is not simply an act of faith; it is an act of reckless rebellion against the values of an increasingly insular and fragmented city. Winners’ Chapel is not the church of Nairobi’s elite (though this is changing), nor is it the church of the old guard, who have encased themselves in Anglicized rituals. A Facebook user summed up the project succinctly when he stated, “This is indeed heaven on earth.” Tempting as it might be to refer back to Bishop Oyedepo’s charitable and democratic mandate to “liberate the world of all oppression,” the implication of this singular statement reveals the consumptive nature of church attendance.9 Heaven is not an exclusive club; it is a state of mind, one that can be built to welcome the newly liberated here on earth.

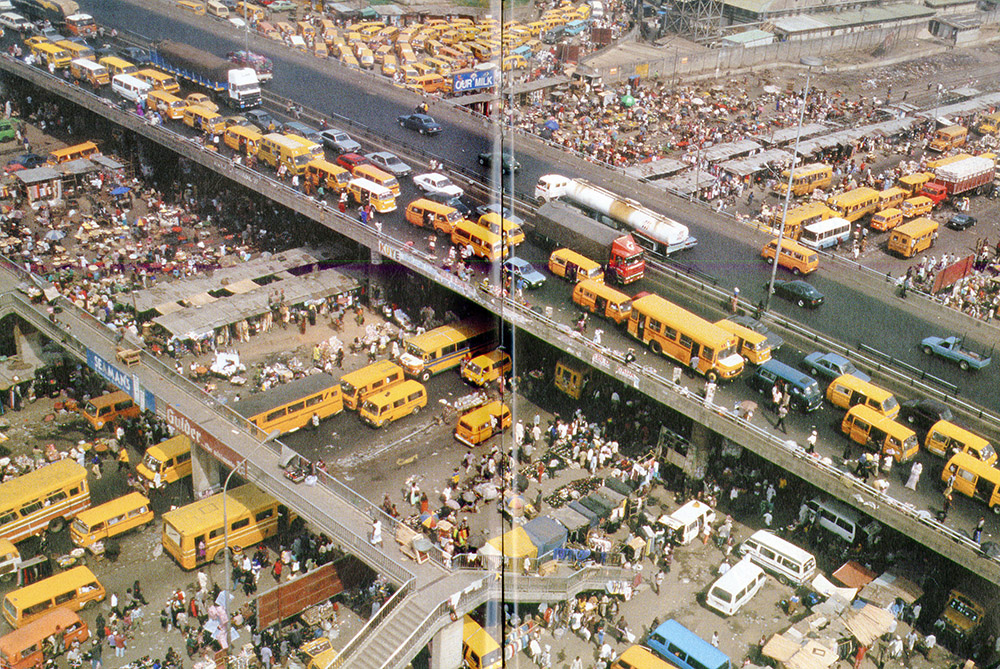

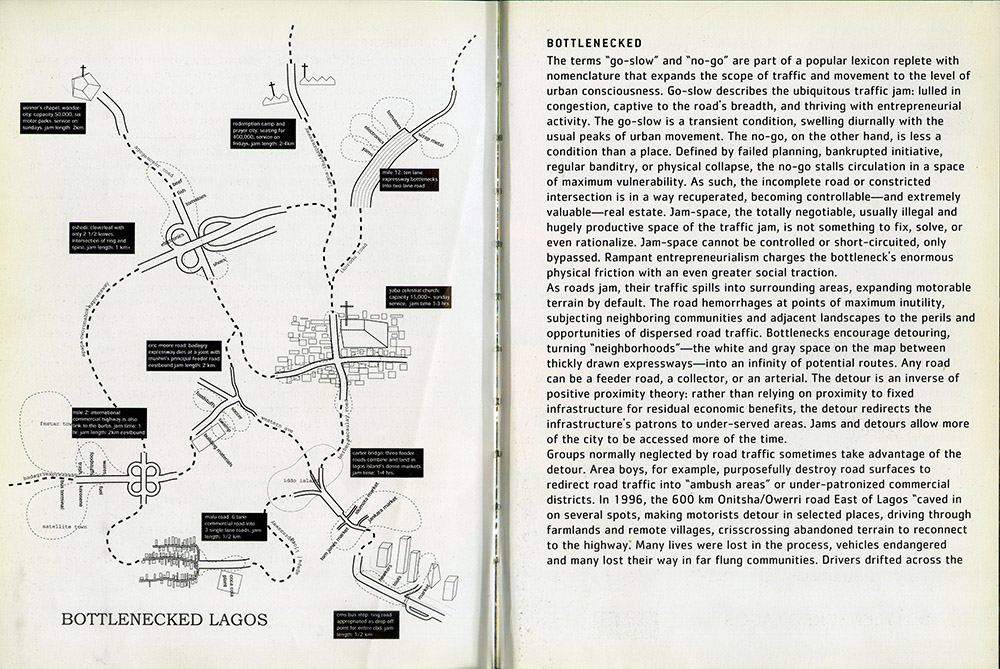

Across the continent in Lagos, where megachurches have flourished since the late ’80s, the patchwork of ecclesiastical nodes has come to dominate the flow and function of the city. The architect Rem Koolhaas was so enamored by the city of Lagos that he produced a series of research projects (one published) that artfully toed on the right side of architectural fetish and the postcolonial imagination.10 11 In Mutations (2001), Koolhaas’ celebrated study of urbanity, the chapter on Lagos includes a series of sublime aerial photos of the Lagos augmented by diagrams of megachurches and their associated traffic jams. Taken together, these images are described by the geographer Matthew Gandy with a sense of urban, mathematic sublime: “There is a faint resemblance here to a giant Mandelbrot, or perhaps a Deleuzian genetic algorithm.”12 The significance of megachurches on the urban experience in Lagos is striking given the legendary failure of the city’s infrastructural skeleton. The megachurch, it could be argued, is a product of monumental urban failure.

It is too early to speak to the restructuring of Nairobi along similar evangelical lines. Certainly, Nairobi’s traffic defies mathematical precision in its wanton disregard of flow and logic. It is, however, not entirely the case that Lagosian urbanity exists at the end of a trajectory upon which Nairobi’s has set off.13 Stuck on Mombasa Road on a Sunday morning, however, one wonders about the city’s social relations and its ever-splintering factions of classes, races, and religions and the attendant urban reimagining; the inversion of public space as enclosure, the intersection of shopping meccas and neo-baroque megachurches. All these buildings are erected in isolation, and the variations in taste and scale say more about their users than anything else built in postcolonial Nairobi.

African Socialism and Its Application to Planning in Kenya is perhaps the most notable government policy paper with anything resembling a spatial framework ever published by the Kenyan Government.14 Unlike some postcolonial states, Kenya has never been drawn to self-aggrandizing architecture or urban planning. In the postcolonial period, attempts have been made at erecting monuments in Nairobi, but very few of these monuments pretend to concretize what Lawrence J. Vale describes at the “the slippery notion of national identity.”15 African Socialism is self-reflective but only goes so far in addressing structural inequality. Because it is inward looking, the document betrays a uniquely Kenyan brand of fatalism, masquerading as common sense. The narrative is simple: the young Kenyan nation is resource-poor, and so it must be thrifty for the sake of development. In the paper, the mitigating circumstance bridging grinding poverty and the searing halo of development is postulated as planning, or better put, it is the power to control a very uncertain future. Except for the Kenyan government’s need to see African faces in all the state and business positions that mattered, African socialism was quickly abandoned as policy.16

However, the document is useful to bear in mind while thinking about the “Faith Theatre” at Winners’ Chapel. Embedded within the DNA of African Socialism is the nascent theory of harambee—the concept of self-improvement through mutual assistance.17 No doubt the spirit of harambee is evoked as Winners’ Chapel seeks to build the Faith Theatre or any other large development. No expense will be spared because, at the end of the day, the church embodies its consciously stratified congregation—in a city like Nairobi, where slum fires and arbitrary evictions are common, the permanence of a church sanctuary is vital. Winners’ Chapel endures because it is built with a spirit more binding than nationalism and more euphoric than political liberation. It is, to paraphrase Koolhaas, the best kind of architecture because it is prepared for the worst catastrophe.18 The catastrophe is not the collapse of society but the opposite—the lack of expectation that the state will act differently, the lack of a concerted nation-building endeavor because that would require public consensus. In this framing, seductively rendered images fill the void left by the absence of the state. Winners’ Chapel lives up to its name knowing full well that the lives of its congregants are precarious. Who knows what tomorrow will bring? Not David Oyedepo and certainly not the Kenyan government. This is radical politics—self-emancipation through the rituals of group-think.

A more recent incarnation of Kenya’s bourgeoisie ambition, Vision 2030, billed as a transformative economic blueprint, attempts to replicate Singaporean state capitalism, taking the rendered image from the idealistic into the fantastic. This is a development project for the postmodern age and departs from earlier postcolonial economic development plans. Here the Kenyan state attempts to construct what Okwui Enwezor characterizes as postmodernism’s obsession with “the grand narrative.”19 The narrative is dramatic spatial transformation through access to global capital; the fantasy is towers flowering upward in the Kenyan savannah.20 Viewed this way, Winners’ Chapel is personal aspiration rendered in steel trusses, corrugated metal, and plaster. It sits comfortably within the prevailing development paradigm. The pastor and the forces of national development are in congress with each other; the congregation is both audience and benefactor.

Nairobi’s bourgeoisie will continue to be ambivalent about these subtle shifts in their city. They have retreated elsewhere to more consciously consume because they have choice to do so, though many of them may turn to Winners’ Chapel for spiritual and emotional sustenance. In this city, nothing is guaranteed, not even class status. And this is perhaps the point. Nairobi’s middle class isn’t a fixed position nor are its values and politics collectively articulated. Winners’ Chapel however, will continue its steadfast mission to literally and metaphorically enrich the lives of its congregants. Its radiant vision of the future may attract a more affluent congregation grateful for the certainty of the church’s message. This is the church’s final incarnation: the church as social condenser and swaddling cloth. At the end of the day, salvation in this world is personal, and it is increasingly distorted by the power of images and the internet. In this era of individually tailored information, there is something to be said about the unifying power of a radiant vision and an individual’s ability to choose whether to buy into it. It is here that the great line from Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil takes on an ominous meaning: “He has chosen to give up his privileges, but he can do nothing about the privileges that have allowed him to choose.”21

-

Nairobi was founded as a railway depot in 1899. ↩

-

Richard Kamau, “Nairobi’s Largest Church, Winners’ Chapel, Set to Be Demolished,” Nairobi Wire, March 18, 2014, link. ↩

-

Winners’ Chapel current church sanctuary was opened by William Ruto, Kenya’s deputy president, in 2013. Increasingly, churches like Winners’ are becoming essential canvassing grounds for politicians. ↩

-

Winners’ Chapel first opened in Nairobi in 1998. The original church could accommodate 3,500 members. See Allen Heaton Anderson, To the Ends of the Earth: Pentecostalism and the Transformation of World Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). ↩

-

Winners’ Chapel alleges to have branches in sixty-five countries, though no comprehensive list is publicly available. While the church was not forthcoming in releasing this information, it appears that each national “branch” of the church is operationally autonomous as is evidenced by the separately maintained websites and Facebook pages. ↩

-

The Church’s website states that following an eighteen-hour vision from God, Bishop David Oyedepo was tasked with “liberating the World from all oppressions of the devil through the preaching of the Word of Faith.” Visit “The Mandate,” Winners Chapel International, link. ↩

-

“Exposing Deception,” emperorundertheking.blogspot.com, January 26, 2016, link. ↩

-

Okwui Enwezor, Gestures of Affiliation (Munich: Haus der Kunst, 2015). ↩

-

Rem Koolhaas et al., Mutations: Rem Koolhaas, Harvard Project on the City, Stefano Boeri Multiplicity, Sanford Kwinter, Nadia Tazi, Hans Ulrich Obrist (Barcelona: ACTAR, 2001). ↩

-

A second book titled Lagos Handbook, or a Brief Description of What May Be the Most Radical Urban Condition on the Planet, was prepared by Koolhaas and students of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design but never published. Critics challenged Koolhaas’ simultaneous view of Lagos as both future and apocalypse. ↩

-

Matthew Gandy, “Learning from Lagos,” New Left Review, no. 33 (May–June 2005): 36–52. ↩

-

Koolhaas and his team of researchers were famous for stating the axiom, “…Lagos is not catching up with us [the West]. Rather we may be catching up with Lagos.” See Koolhaas et al., Mutations. ↩

-

The underlying principle of urban planning is summarized simply as the ordering of “land use and layout, and locational, transport, and design problems in both rural and urban areas.” Government of Kenya, African Socialism and Its Application to Planning in Kenya, session paper no. 10 (Nairobi: Government Press, 1965), 49. ↩

-

Lawrence J. Vale, Architecture, Power, and National Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992). 134. ↩

-

As early as 1965 the paper was described by critics as “neither African nor Socialist;” with some critics in the government openly skeptical of the policy document. David William Cohen, “Perils and Pragmatics of Critique: Reading Barack Obama Sr.’s 1965 Review of Kenya’s Development Plan,” African Studies, vol. 74 , issue 3 (July 2015): 1–23. ↩

-

The concept of harambee was put forward by Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, as a way for society to collectively address the gaps between community need and the government’s limited resources. This evolved over time, expanding to everything from wedding and funeral expenses to school fees (and school building) and medical costs. Interestingly, the newly formed coalition government in 2002 attempted to ban harambee in an attempt to curb corruption associated with the KANU regime that had ruled Kenya since 1963. ↩

-

Koolhaas here was discussing the Cartesian tower’s defense mechanism. Here it can be applied against the more existential threats of urban life in Nairobi. Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (New York: Monacelli Press, 1994), 254. ↩

-

Enwezor makes the distinction between postmodernism and postcoloniality. He states that “…postcoloniality…[seeks] to sublate and replace all grand narratives through new ethical demands on modes of historical interpretation.” Okwui Enwezor, “The Black Box,” in Documenta 11_Platfrom 5: Exhibition Catalogue, ed. Heike Ander and Nadje Rottner (Ostfildern, DE: Hatje Cantz, 2002), 45. ↩

-

Vision 2030’s flagship project is Konza City, a proposed smart city seventy kilometers east of Nairobi, nicknamed the “Silicon Savanah.” The moniker also broadly refers to Nairobi’s tech industry. ↩

-

Chris Marker, Sans Soleil (Argos Film, 1983). ↩

Kahira Ngige is an urban planner and a graduate student currently attending the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). Prior to attending the GSD, Kahira worked as a planning consultant in London—mainly working with local governments across England on developing retail, housing, and economic development plans and policies. Currently, Ngige’s research interests include the globalized dissemination of culture and aesthetics and the role of large-scale infrastructure projects in galvanizing national identity. Kahira Ngige was born and raised in Nairobi, Kenya.