When I was in high school, my dadi ji (paternal grandmother) would recruit me once every few weeks to accompany her around the city to complete random odd tasks. They would range from changing the antifreeze in her silver 2002 Oldsmobile Alero to installing new outdoor lighting for her garden-turned-farm to doing a few hours of seva (selfless service) at the local gurdwara (Sikh temple). Fast-forward nearly a decade, and here I was, preparing myself for another afternoon of work with my grandmother.

Standing in the foyer of my family home in a fading salwar kameez and a pair of heavy-duty Reebok sneakers, dadi ji yelled in Punjabi: “Sajdeep! Go open the back door for me.” She was here looking for the ladder. Upon finding it, I helped her carry the twenty-six-foot steel structure from our toolshed into the back of her car. When I tried to snap a photo of her afterward, she defiantly slapped the camera out of my hands. The plan today was to clean the gutters of her garage.

In 1962, the Canadian government issued reforms to immigration policy that eliminated quotas based on national origin, opening borders to migrants from Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America.1 It is within this context that my grandfather left Bradford, United Kingdom—the current “Curry Capital of Britain”—with his wife and two young sons to settle in Galt, Ontario, in 1966.2 Like other small towns in the area, Galt boasted a thriving textile industry, perfect for the enterprising couple.3 Migrating across imperial geographies of the British textile manufacturing industry, my grandfather had lined up a position for himself as the night-shift foreman at Canadian Synthetic Fibres Limited. Having worked as a seamstress in the United Kingdom, my dadi ji joined him on the factory floor until the company folded in the early 1990s.

In 1973, the aspiring “Manchester of Canada” joined the neighboring industrial towns of Preston and Hespeler to become the City of Cambridge. Entering the late twentieth century alongside an emergent service economy, Cambridge slowly lost its urban manufacturing base. By the early aughts, most factories had closed down, and urban sprawl was turning the city farther away from its original industrial boroughs. New middle-class “ethnoburbs” emerged on the outskirts of the three downtown cores, while Galt, Preston, and Hespeler proper—home to many retired factory workers and their kin—quickly fell into disrepute, written off as hotbeds of “crime” and “drugs.” Old Galt, heralded for its “scenic views, old world charm, towering churches and grand mansions,” remained the only safe haven for the Anglo-Saxon managerial and proprietary class that has long governed the city.4 It is unsurprising that in the past ten years, downtown Galt has become the primary site for urban revitalization efforts and will soon be home to the aptly termed “gaslight” district.

In their early years in Canada, my grandparents moved between apartment buildings near their factory in Northeast Galt. It was only after hikes of the Ontario minimum wage in 1974 that my grandparents were able to buy a split-level home with a two-car garage on the edge of the newly consolidated city. After our family expanded in the early 1990s (two arranged marriages and children on the way), it was time to move again. We decided to move into the heart of Old Galt—in part so that I could attend a better elementary school. Promising classrooms filled with second- and third-generation white legacy students and a robust French immersion program, Highland Public School laid the foundation for a journey toward whiteness that involved extolling the virtues of white liberal multiculturalism that masked an underbelly of xenophobic violence. When I was young, family tensions led my grandparents to move out of our house into a separate bungalow. Newly built in 1997 as part of suburban expansion, my grandparents’ home is located nearby, just slightly southwest of Old Galt.

One of the ways my grandparents carved their racialized migrant sensibilities and eccentricities into the postwar suburban landscape of Cambridge was by repurposing buildings. They have turned garages into courtyards, dens into prayer rooms, and cheap farmhouses into gurdwaras. Old family photographs show how my baba and dadi ji constructed, used, and at times abandoned, these retrofitted architectural spaces.

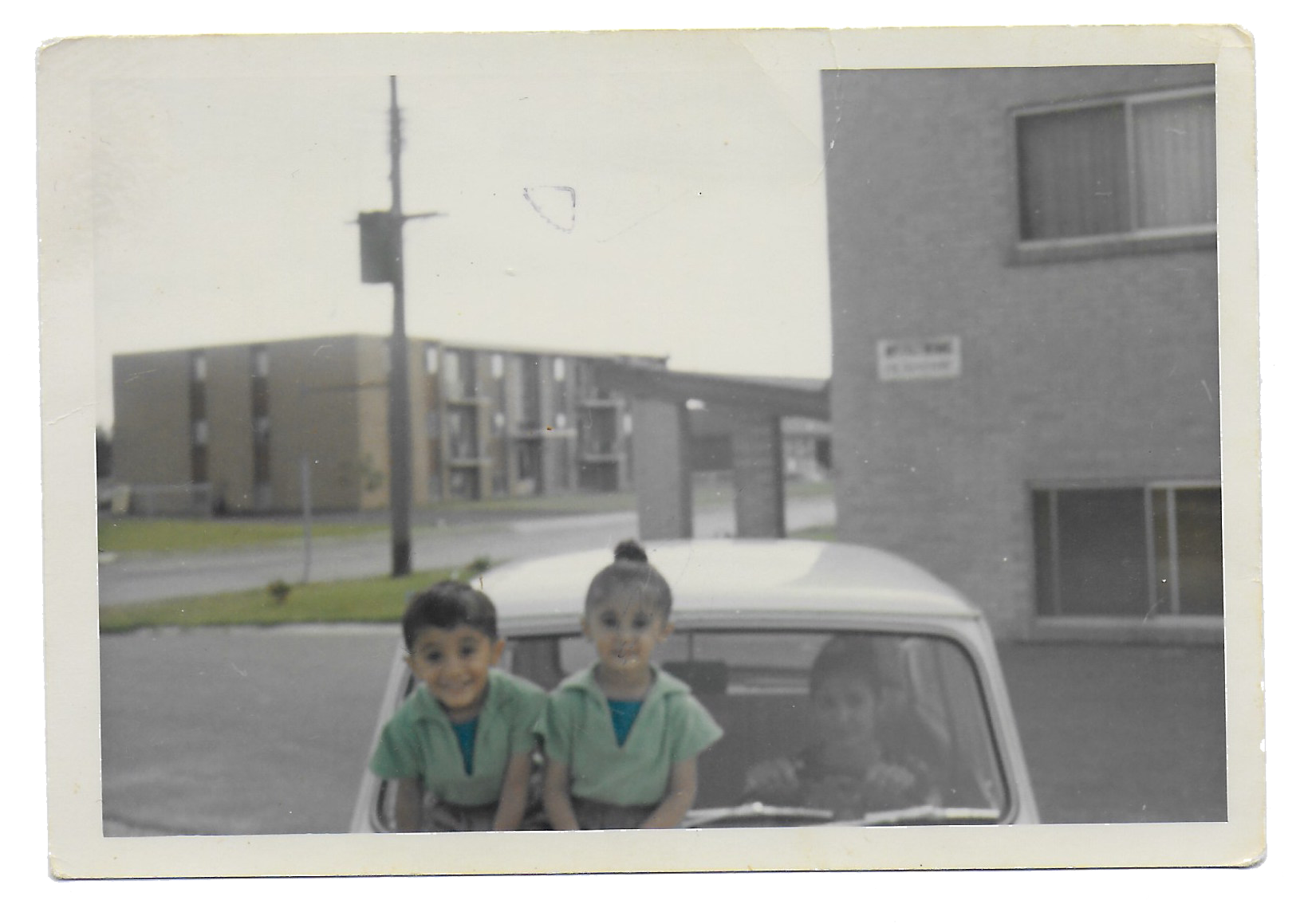

As I placed the ladder into the trunk of her car, I remembered a photograph I had found in my parents’ basement of my dadi ji sitting in the family car, a 1964 “Mark I” Mini, with her two young sons propped up on the hood. Literary scholar Deborah Clarke explains that “in providing access to the public sphere—to work, to escape—the car transformed women’s lives as profoundly as suffrage.”5 My dadi ji first learned to drive after moving to Canada from England. The color photograph, taken outside of their first apartment at 54 Hilltop Drive in East Galt, is visually split down the middle. Either incorrectly developed or fading from time, my grandmother—cast in black and white on the right side of the photo—slowly fades into the background. The photograph marks the labor and sacrifices my dadi ji—long derided as traditional, backward, and anti-modern by her children and grandchildren—put into driving her family forward.

and dad sitting on the hood, circa 1969.

The automobilization of family life tends to strain gender relations.6 While my grandfather and his two sons drove sports cars, my dadi ji was relegated to sharing the family sedan. Because she was living in a household of mobile men, it wasn’t until after my grandfather had a stroke in the early 2000s that my dadi ji gained full access to a car. Becoming the only driver, she took on the responsibility for repairing the family rental properties, restocking the toolshed, and driving her husband around town. Her 2013 Ford Taurus serves as an essential tool in “juggling the everyday time economy.”7 While the car is often treated as a tool that helped to facilitate women’s departure from domesticity, it is also clear that gaining control over the family car gave my dadi ji a newfound autonomy over domestic space—particularly its most coveted space of masculinity, the garage.

Driving up to my grandparents’ house, you notice how inconspicuously the bungalow blended into the cookie-cutter landscape. Looking at the detached bungalow through Google StreetView, you can see how the house remains indistinguishable from its neighborhood context. As architectural theorist Dana Cuff explains, the prototypical postwar suburb “homogenizes a group of strangers through exterior repetition and erodes presumptions of interiority.”8 Entering the interior of the house, you learn that my grandparents have rented out the basement to a tenant, converted the den into a prayer room, transformed the backyard into a mini farm, and retrofitted the garage with kitchen appliances. Eliding formal documentation, the modifications that my grandparents have made to their residential garage are gleaned only by studying other forms of evidence—family photographs, oral histories, collected ephemera, and my own documentary photographs.

The mass distribution of the automobile and the rise of private home ownership during the interwar years encouraged the growth of suburban housing developments across North America.9 Residential garages were first designed and constructed as “do-it-yourself” projects by blue-collar workers outside city centers who built shelters for their new cars—the first generation of cheap automobiles mass-produced by Ford, General Motors, and other American manufacturers.10 Despite the popularity for garages, prominent postwar builders such as Joseph Eichler abandoned these rudimentary spaces in many models, often substituting unenclosed carports.11 Under an emergent “do-it-yourself” ethos, suburban men adapted garages and carports to function as workshops and toolsheds.

J. B. Jackson and other historians have demonstrated how residential garages transformed through the latter half of the twentieth century from simple carports into large, physically connected elements of the suburban home that serve various alternate functions beyond sheltering automobiles.12 Investigating how one particular American family lived in a suburban bungalow built by Eichler Homes, feminist architectural scholar Annmarie Adams describes how this family “preferred to park their two cars on the driveway and street in order to gain an ad hoc ‘games room’ for the kids.”13 While Adams urges us to reconsider how suburban domestic spaces are adapted and used by residents, it has been difficult to fill this disciplinary and archival blind spot. Focused on how migrants have transformed public spaces such as metropolitan centers, religious institutions, and commercial spaces, establishing ethnic enclaves and “ethnoburbs,” scholars of race and ethnicity, cultural landscapes, and vernacular architecture have left the private, domestic interior largely uninvestigated.14

Bringing the private interior into architectural discourse entails developing new collaborative documentary methods. Over the past year, I have worked for the Family Camera Network—a SSHRC-funded collaborative research project aimed at building a public archive of family photography at the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archive and the Royal Ontario Museum. I have learned about the infrastructure and resources necessary to make such large-scale outreach and collection projects operational while witnessing the dedication and care that made this one so successful. Gathering, documenting, and storing residents’ photographs, oral histories, and ephemera to rethink the architecture of domestic space involves researchers entering into the carefully guarded, private, and intimate realms of family life, extracting documents for the public record. It is a task mired in ethical considerations.

Opening the door to my dadi ji’s garage, you confront organized chaos. At the center are two lawn chairs where my grandfather sits from spring to fall, greeting friends, passersby, and visitors in his off-white turban and kurta pajama. All around, clusters of auto parts and pantry items are placed side by side. I watch as my dadi ji locates the gloves and appropriate hose nozzle to clean the gutters with ease. There is a magic to how she navigates the space, scanning the seemingly unidentifiable, useless-looking objects to find the appropriate item. Inquiring further, my dadi ji explains her method: items are arranged according to use and ease of access. In short, things that my grandfather might need—his spare cane, paper towels, a water bottle—are placed at counter height, while replacement parts like ceiling lights and bottles of disinfectant are stacked up top.

Most striking are the kitchen and laundry appliances that are symbiotically installed on the back wall. My grandmother explained that the decision to purchase a front-load washer was intentional so that the machine could double as a countertop for her second kitchen. The stove is helpful for when she cooks tadka (the tempered spices, ginger, garlic, and onions that form the base of most Punjabi cuisine), as well as jalebis, samosas, and other deep-fried snacks so that the smell of the frying oil doesn’t enter into “the clothes, furniture, and carpet.” When I asked about fire safety, she told me that the garage door was always propped open for ventilation when she cooks. When I warned her about the risks of poor ventilation, she replied sternly.

“The firefighters are very good people.”

She slapped my shoulder lightly.

“Knock on wood, you shouldn’t say such things.”

Her “open-door policy” blurs the line between garage and neighborhood. My assumption that my grandparents’ visual and olfactory otherness would press cultural norms past tolerable boundaries for their neighbors was wrong. Rather, the semi-public cooking offered an opportunity to facilitate kinship and mutual understanding. “When I’m working in the garage, those two men who live next to us come every week to visit and we chitchat a bit,” my dadi ji explains. “They are really good and thoughtful neighbors. One of them sometimes cuts our grass and removes the snow with the snowblower.”

Dadi ji’s repurposing of the garage compels us to think about the origins of these practices. Unlike the do-it-yourselfers and suburban men that preceded her, my grandmother did not find inspiration for her garage from popular magazines or television shows. Rather, the modifications reflect life circumstances and signify my grandparents’ sensibilities as Jatt Sikhs—religious landowners and agriculturalists from Punjab, a province in northern India. Describing her childhood house in rural Punjab, my dadi ji recalled family life in the courtyard, where an open kitchen was installed for cooking in the summer, a few manjaas (traditional woven furniture) were laid out as seating for visitors, and a section was reserved for domestic and agricultural tools.15 Inspired by the Punjabi domestic courtyard, her garage reroutes the kitchen, workshop, and living room into a singular space. The documentary photographs that I took reveal how her garage-turned-courtyard straddles public and private, disturbing the monotony of North American suburbia with the particularities of Punjabi diasporic life.

The family life, home, and future that my dadi ji envisions is at risk of disappearing on multiple fronts. As her body ages, it is harder for my grandmother to tend to her husband’s needs and complete household tasks. Her oldest son doesn’t speak with her anymore, and her two grandchildren repeatedly refuse to marry and have children—my dad jokes that he is the only “good boy.” While returning to Punjab again is out of the question, I know that my dadi ji is skeptical of the modernizing province for other reasons. A few years ago, my grandfather sent remittances to his brothers to build up our ancestral home. Decked out with modern luxuries, the house is modeled after a large two-story North American suburban house. Her diasporic garage is a vestige of traditional rural Punjabi life in a world ravaged by colonial capitalist modernity. “Every place is becoming the same,” my dadi ji tells me.

As I held the ladder while my dadi ji removed leaves from the gutter, I considered how these photographs I had taken, presented without context, might confirm racial fears about the “dirty,” “cramped,” and “unkempt” living space of new migrants. In the end, though, architectural photographs themselves hold no clear-cut politics—it is only with context that they can be mobilized for varying political aims, from architectural reform to racial exclusion. While writing about these photographs, it was easy to locate my dadi ji as an endangered figure of racial and gendered exploitation, to write about her garage-turned-courtyard as a story of endurance and possibility. But that would fit too neatly into family myths that quietly weave together Indo-Aryan tribal nobility, Sikh martyrdom, and Jatt liberation into a sacred thread while setting aside the grim reality of caste apartheid in Punjab as an afterthought.

Originally nomadic pastoralists living around the Indus Basin, Jatt tribespeople settled into agricultural life in early modern Punjab due to the proliferation of new architectural technologies of water control such as small basin embankments (bunds), traditional wells, and Mughal canals that made commercial agricultural production economically viable in the face of erratic and undependable monsoons.16 Settling into rural village life, many Jatt people converted to Sikhism during this period. Emerging from anti-caste sant (saint) traditions in fifteenth-century Northern India, Sikhism was rooted in an egalitarian ethic that refused practices of untouchability.17 But despite coalescing across caste lines through the formation of the Khalsa (national Sikh congregation) in 1699, Dalit historian Raj Kumar Hans explains that Hindu caste-centric practices returned to Sikhism during Sikh imperial rule through the rise of Sanatan Sikhism (Hinduized Sikhism) and the appointment of Hindu mahants (priests) to various gurdwaras.18 Under the mahant-system, Dalits were slowly removed from religious administration and prevented from bathing in the sarovar (holy water) at the Golden Temple. It is within this context of Sikh nation-building, imperial militarization, agricultural settlement, religious reform, and caste-based exclusion that the British colonial state sought to fold the Punjab into its colonial-capitalist machinery by allying themselves with the Jatt Sikhs.

In 1900, the British Raj passed the Punjab Alienation of Land Act, which divided the Punjabi people along a new agricultural axis: “traditional agricultural tribes” (including Jatts, Rajputs, etc.) against “traditional non-agricultural tribes” (including Chamars, Churhas/Bhangis, Dalits, etc.). The new system of classification prevented “traditional agricultural tribes” from alienating their land or mortgaging it for extending periods, except to other zamindhars (agricultural landowning castes). Beginning in the 1880s and continuing into the 1940s, the colonial government worked to raise the agricultural productivity of Punjab by irrigating over 10 million acres of arid land. Later known as the Punjab Canal Colonies, the land was distributed primarily to the Jatt landowning families, either through resettlement projects or as rewards for recruits who had served in the British army.19 Together, these shifts laid the foundation for an emergent agricultural, landowning tribe of Jatt Sikhs to enter the upper ranks of South Asian caste society and solidify economic and political power in the region during the twentieth century. Hans explains that after the Dalits of Punjab were dispossessed of land and rendered as a free supply of agrarian labor for the traditional agricultural tribes, under colonial law they became “extremely vulnerable…completely thrown to the mercy of the Jatts.”20 It is through these conditions of possibility and subjugation, as the daughter of propertied Jatt Sikhs, that my dadi ji grew up in her idyllic ancestral home in rural Punjab and first learned how to work the land.

Perhaps we might just as well consider my grandmother’s house as a document of Canadian settler colonialism—another chapter in the expropriation of indigenous land around the Grand River. Issued on October 25, 1784, the Haldimand Proclamation authorized the Six Nations of the Grand River to possess all of the land six miles on each side of the Grand River (O:se Kenhionhata:tie in Mohawk/Kanien’kéha, meaning “Willow River”), from its mouth in Lake Erie to its source in Central Ontario. Amounting to approximately 950,000 acres of land in total, it was supposed to be held in trust by the British, Ontarian, and later Canadian governments for the Six Nations “and their posterity to enjoy forever.”21 Last year Haudenosaunee scholar Susan Hill released “The Clay We Are Made Of: Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River,” a monograph that uses Haudenosaunee knowledge and records to provides a nuanced and accurate account of how parts of the Grand River Territory were expropriated by the Canadian government.22 A comprehensive report published by the Six Nations Lands and Resources Department in February 2015 detail precisely how the British government instead sold those lands and used the revenues to finance Canadian development projects (from cities and universities to dams and railways) with little or no return to the Six Nations.23 Dividing the land into tracks and plots of property ready for sale, settler colonists laid the foundation for industrial, commercial, and residential development along the Grand River. Indigenous protesters have repeatedly blocked these illegal development schemes. In 2006, the Six Nations of the Grand River gained national and international attention for reclaiming a parcel of land that real estate developers were intending to build upon to extend the dormitory community of Caledonia.24 According to Shiri Pasternak and Tia Dafnos, these protests are precisely how “Indigenous peoples interrupt commodity flows—by asserting jurisdiction and sovereignty over their lands and resources in places that form choke points to the circulation of capital.”25

Arriving with zamindhar sensibilities, my grandparents easily found a second home on Ohswe:ken (Grand River Territory). Locating colonialism as the structure that compels settlers and arrivants like my family “to cathect the space of the native as their home,” Chickasaw decolonial scholar Jodi Byrd reminds us not to “sacrifice indigenous worlds and futures in the pursuit of the now of the everyday.”26 While we scattered the leaves from the gutters of the garage in my grandmother’s backyard, I started recounting this story of land expropriation on Turtle Island in Punjabi, using the language of stolen zameen (property) to explain our complicity within the Canadian settler colonial project. Patiently waiting for a response, I was slightly shocked when my dadi ji started talking about her vegetable garden. “I stopped using fertilizer a long time ago,” she told me flatly. Frustrated by what I imagined was a deferral, I steered the conversation back to the issue of stolen property. Reflecting later, I realized what was lost in translation, lost in colonization. My grandmother treated the term zameen as both property and the earth itself. For her, settler colonialism is constituted through both land dispossession and soil degradation. As an ardent agriculturalist whose relatives have experienced the misgivings of the Green Revolution, she witnessed the unsustainable irrigation, chemical mistreatment, and monoculturalization of soil around the Grand River as part and parcel of the Canadian settler colonial project.27 As she opts for precise planting techniques over chemical fertilizer, feeding wild rabbits instead of scaring them away, using organic instead of modified seeds, and veering away from her zamindhar sensibilities, my dadi ji is wary of industrial agriculture and colonial land development schemes. But she is only one person, and dismantling the colonial orders of Ontario and the Punjab is another task entirely.

Hashing it out with my dadi ji on the phone and in her garage, I have found an opening in the void, in the gulf of consciousness, language, and knowledge that separates us. The other day, my dadi ji called me asking if I had heard about the state of emergency that had been declared in Six Nations in late February 2018 due to flooding. My attention elsewhere, I had missed it. After recounting the incident and then talking at length about the architectures of water control in Punjab, she lamented through a hollowed laugh, “The gore (white people) have changed the way the water works here too, haven’t they?” Witnessing the colonial-capitalist linkages that pull Ontario and Punjab into a multiplying story of technocratic rule, perhaps my dadi ji offers an entry point for forging an alternative ethics of diasporic Sikh Punjabi life. An ethics that will be worked out with anyone willing to step inside her garage.

-

Judith M. Brown, Global South Asians: Introducing the Modern Diaspora (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 4. ↩

-

“Curry Capital: Bradford Takes Title for Fifth Consecutive Year,” BBC News, October 20, 2015, link. ↩

-

For history of the British imperial textile industry see Eric J. Hobsbawm and Chris Wrigley, Industry and Empire: From 1750 to the Present Day (New York: The New Press, 1999) and The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200–1850, ed. Giorgio Riello and Prasannan Parthasarathi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). ↩

-

Derek Flack, “This Small Town in Ontario Will Transport You to Europe,” BlogTO, August 2017, link. ↩

-

Deborah Clarke, Driving Women: Fiction and Automobile Culture in Twentieth-Century America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), 3. ↩

-

For more on the relationship between gender and suburban automobility, see Cindy Donatelli, “Driving the Suburbs: Minivans, Gender, and Family Values,” Material Culture Review/Revue de la culture matérielle, vol. 54, no. 1 (Fall/Automne 2001): 84–95. For more general analyses about cars and gender, see Daniel Miller, Car Cultures (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2001), and David Gartman, “Three Ages of the Automobile: The Cultural Logics of the Car,” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 21, no. 4–5 (October 2004): 169–195. ↩

-

Mike Featherstone, “Automobilities: An Introduction,” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 21, no. 4–5 (October 2004): 13. ↩

-

Dana Cuff, “Enduring Proximity: The Figure of the Neighbor in Suburban America,” Postmodern Culture, vol. 15, no. 2 (January 2005), link. ↩

-

Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 39. ↩

-

Steven M. Gelber, “Do-It-Yourself: Constructing, Repairing, and Maintaining Domestic Masculinity,” American Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 1 (March 1997): 95. ↩

-

Karal Ann Marling, As Seen on TV: The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s (Cambridge UK: Harvard University Press, 1996). ↩

-

J. B. Jackson, “The Domestication of the Garage,” in The Necessity for Ruins and Other Topics (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1980): 108–111. For more general studies of the suburban garage, see Gary Daynes, “Cars, Carports, and Suburban Values in Brookside, Delaware,” Material Culture, vol. 29, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 1–11, and David Gebhard, “The Suburban House and the Automobile,” in The Car and the City: The Automobile, the Built Environment, and Daily Urban Life, ed. Martin Wachs and Margaret Crawford (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991): 106–123. ↩

-

Annmarie Adams, “The Eichler Home: Intention and Experience in Postwar Suburbia,” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 5 (1995): 172. ↩

-

Key texts on ethnic space and cultural landscapes in North America include Wei Li, Ethnoburb: The New Ethnic Community in Urban America (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009) and Arijit Sen and Lisa Silverman, Making Place: Space and Embodiment in the City (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2013). For analyses specific to southwestern Ontario and the Greater Toronto Area, see Michael Buzzelli, “From Little Britain to Little Italy: An Urban Ethnic Landscape Study in Toronto,” Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 27, no. 4 (October 2001): 573–587 and Jason Hackworth and Josephine Rekers, “Ethnic Packaging and Gentrification: The Case of Four Neighborhoods in Toronto,” Urban Affairs Review, vol. 41, no. 2 (November 2005): 211–236. ↩

-

For an account of rural Punjabi architecture, see Gautam Bhatia, Punjabi Baroque: And Other Memories of Architecture (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1994). ↩

-

For further information on the Jatts tribespeople and environmental history in the Punjab, see David Gilmartin, Blood and Water: The Indus River Basin in Modern History (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015); Chetan Singh, Region and Empire: Panjab in the Seventeenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); and Neeladri Bhattacharya, “Pastoralists in a Colonial World,” in Nature, Culture, Imperialism: Essays on the Environmental History of South Asia (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995): 49–85. ↩

-

For a detailed history of Sikhism, see Arvind-Pal S. Mandair, Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009). ↩

-

Raj Kumar Hans explains that there is no work on Sikh history or tradition in English that has been written from the Dalit perspective. His work generously offers the insights of multiple generations of Punjabi Dalit activist-scholars to English-language speakers. For further details, see “Making Sense of Dalit Sikh History,” in Dalit Studies (Duke University Press, 2016): 131–151. ↩

-

For more information about the Punjab under British colonial rule, see Rajit K. Mazumder, The Indian Army and the Making of Punjab (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2003); Richard Fox, “British Colonialism and Punjabi Labor,” in Labor in the Capitalist World Economy (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993); and David Gilmartin, “Migration and Modernity: The State, the Punjabi Village, and the Settling of the Canal Colonies,” in People on the Move: Punjabi Colonial, and Post-Colonial Migration (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2004). ↩

-

Hans, “Making Sense of Dalit Sikh History,” 147. ↩

-

E. Reginald Good, “Lost Inheritance: Alienation of Six Nations’ Lands in Upper Canada, 1784–1805,”Journal of Mennonite Studies 19 (January 2001): 92–102. ↩

-

Susan M. Hill, The Clay We Are Made of: Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2017). ↩

-

For a complete list of organization that used Six Nations monies, including the City of Toronto, McGill College, Welland Canal Company, Brantford Episcopal Church, Erie & Ontario Railroad Company, and others, see Land Rights: A Global Solution for the Six Nations of the Grant River (Six Nations of the Grand River, 2015), link. ↩

-

Susan M. Hill, “Conducting Haudenosaunee Historical Research from Home: In the Shadow of the Six Nations–Caledonia Reclamation,” the American Indian Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 4 (Fall 2009): 479–498, link. ↩

-

Shiri Pasternak and Tia Dafnos, “How Does a Settler State Secure the Circuitry of Capital?” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35 (June 2017), link. ↩

-

Jodi A. Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), xxxix. ↩

-

On the Green Revolution, see Vandana Shiva, The Violence of the Green Revolution: Third World Agriculture, Ecology, and Politics (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2016). ↩

Sajdeep Soomal is a writer, researcher, and curator based in Toronto, Ontario. Working out of the South Asian Visual Arts Centre and the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, Saj is currently writing about drone-proof cities, architectures of suicide prevention, and gharanas in diaspora.