Whatever happened to urbanism? asked Rem Koolhaas in 1995, describing the paradoxical demise of the discipline at the moment that the urban condition appeared ubiquitous. Confronted with the global triumph of urbanization, the city ceased to exist, its traditional rules and precedents, its very ontological foundations, transformed beyond recognition. Urbanists appeared doomed to irrelevance, caught up as they were in the “belated rediscovery of the virtues of the classical city at the moment of their definitive impossibility.”1 It is perhaps revealing then that the urban question featured centrally in Al Gore’s Livability Agenda, announced just a few years later, with a focus on preserving green spaces, easing traffic congestion, fostering community engagement—all while enhancing cities’ competitiveness.2 While urbanism may have been doomed to irrelevance, it appeared urbanists had not, newly charged with a task that captivated the popular imagination—designing the livable city.

One of the most vocal and consistent proponents of urban life has been the architect and urban design consultant Jan Gehl, who has ascended to international superstardom in tandem with the growing global popularity of urban livability. The soft-spoken Dane has pledged to reclaim the city for “people,” as laid out in the best-seller Cities for People, published in 2010.3 The book summarized Gehl’s four-decade-long investigation of human behavior in public spaces, dating back to his Life between Buildings, originally published in Danish in 1971.4 The pedestrianization programs of the Danish architect resonate with municipal planning, policy, and marketing departments, promising to tackle the challenges cities face with “quality of life and livability in the city”—as Gehl advised to New York City under Michael Bloomberg’s mayoralty.5 What are the ingredients to the improbable success of the world-leading emissary of sidewalks, bike lanes, and cafés and of the livability agenda at large? If not for people to live in, then who have cities been for all along? And what is the “life” of the livable city?

Livable City, Creative City

For the urbanists of the livable city, the city triumphs not thanks to modernist urbanism but in spite of it. They see homogeneity, monotony, and dreariness of urban environments as a deplorable heritage of modernist ignorance, wickedness, and megalomania, with the names of Le Corbusier, Robert Moses, and the city of Brasilia appearing unfailingly in any and every diagnosis of urban “unlivability.” The view that urbanism is totalizing, dangerous, and inconsistent with the spontaneity of individual freedoms, popularized since the 1970s by postmodern movements, has been further abetted by the spread of “global post-communism” since the 1990s. Yet this very undoing of urbanism has facilitated a new “urbanism of anti-urbanism,” a “hooray urbanism” that turns modernism’s dialectics of order and spontaneity on its head and places the urbanity of city life at center stage.6

From the Triumph of the City proclaimed by Edward Glaeser to Charles Montgomery’s Happy City and Jeff Speck’s City 2.0, the pundits of hooray urbanism lean heavily on Jane Jacobs’s investigation of the life in and of cities.7 For Jacobs, modern urban planning had been built on a “foundation of nonsense,” contributing to economic and social decline that confronted cities in the 1960s.8 What was needed was to learn from the real world, which Jacobs located on streets and sidewalks—the theater of everyday urban life. Her celebration of urbanity as a case of “organized complexity” concurred with the idea that urbanism was universalizing and therefore dangerous, totalitarian, and inconsistent with individual freedoms.9 Jacobs’s ideas would form the foundation of the livable city movement, emphasizing street-level activity and pedestrianization while simultaneously serving as the linchpin of urban competitiveness that Gore described.

Key to this process was the retooling of urban policies around the creative class, popularized by urbanist and economic geographer Richard Florida, himself an avid admirer of Jacobs.10 In the late 1990s and 2000s, Florida’s case was less a struggle against powerful planners like Robert Moses than it was a polemic about the strategy of urban competitiveness. The decades separating Jacobs and Florida brought the retrenchment of the welfare state, precipitating municipal entrepreneurialism in search of capital where national and federal governments failed cities. Giving an economic spin to Jacobs’s argument, Florida argued that the key to urban competitiveness was neither enterprise zones nor spectacular architecture and the “SOB” (symphony, orchestra, and ballet), designed to attract the wealthy upper classes, but the diversity of everyday urban cultures and atmospheres, appealing to the knowledge workers driving post-industrial economic growth. “[T]he more diverse and culturally rich, the more attractive” cities are, maintained Florida; “[p]laces that attract people attract companies and generate new innovations, and this leads to a virtuous circle of economic growth.”11

Put otherwise, the success of urban competitiveness was pending the lure of human capital by means of Jacobs’s urbanity. Creativity was simultaneously an empirical term and regulative idea, describing a particular class of highly skilled labor, who choose to live where its creative urges can be accommodated, but also the productive capacity of anyone, instrumentalizable for specific policy objectives. “Tapping and stoking the creative furnace inside every human being is ... key to greater productivity,”12 Florida argued, “human creativity is the ultimate source of economic growth.”13 The urban allure of creativity rested on the tension between it being a property of some and a universal potential, a class-based policy passing as public-spirited cultural regeneration—the creative city—because everyone was potentially creative.

This same tension stoked the furnace of gentrification, maneuvered by footloose real estate in search of exploitable gaps between actual and potential rent levels. Florida has apparently backtracked some of his claims in the recently published New Urban Crisis, appealing for policies such as affordable housing.14 This generated a lively debate as to whether he was sorry about his crusade for the creative city.15 However, given that Florida’s case for public investment in infrastructure is still justified by the entrepreneurialization of the poor, “leverag[ing] their talent and productive capabilities and enabl[ing] them to become more fully engaged,” we concur, as he maintained himself, that he is not sorry.16

While the creative city agenda has been undermined by the mounting evidence of its structural complicity in rising urban inequality, livability proliferates unabated as a barometer of urban quality, with swelling lists of most livable cities led by the likes of Monocle, Mercer, and the Economist’s Intelligence Unit. Livability grows increasingly prominent in the discourse of architecture schools, as the global circulation of its “best practices” continues to seduce municipal planning, policy, and marketing departments around the world. If the creative city might soon become a subject of historical study, there is a conspicuous dearth of the critiques of livability as it proliferates based on the good intentions of Jane Jacobs. Where modernist city planning was born out of the late nineteenth-century struggle to contain, plan, and organize capitalist urbanization—to plan for order, so as to facilitate life—the “hooray” urbanism of the livable city would attempt to tie the question of urban life to environmental determinism.

Cities for Homo Sapiens

“Sometimes I would say,” maintains Jan Gehl, “we know much more about the good habitat for mountain gorillas or Siberian tigers than we know about the good urban habitat for Homo sapiens.”17 The main protagonist of the livable city is, therefore, the gregarious human of the human scale: no longer l’homme moyen of the Modulor, defined by mean values of measured dimensions, but the sociable creature of Homo sapiens. For Gehl, the failures of urbanism have to do less with the urban conditions of global capitalism (as Koolhaas argued and cunningly exploited) but more with the naivety and ego of modernism. In his books and presentations, the Danish architect contrasts stark black-and-white images of modernist urbanism to lively and colorful photos of urban street life taken from pre-modern urban contexts. Like Richard Florida, Gehl is another confessed admirer of Jane Jacobs. But where Florida has instrumentalized her work to further an agenda of urban competitiveness, Gehl finds in Jacobs’s celebration of urban life a testimony to timeless requisites of the habitat of Homo sapiens—the city, as it were, before it was distorted by modernist urbanism.18

Citing the Krier brothers among his influences, Gehl identifies the street of the classical city to be “the natural organizational form as a logical consequence of the limitations of human movement and a frontally and horizontally oriented sensory system.”19 But even as the virtues of the classical city have been rediscovered, they have been arguably reduced to the barest parameters of human scale. Streets and squares become “natural” extensions of the sensorimotor qualities of the Homo sapiens species, which is for the Danish architect simply “a linear, frontal, horizontal mammal walking at max 5km/h.”20 There is a sense of morphological determinism to Gehl’s disregard of how the formal evolution of streets and squares might have been determined by historically changing forms of social organization.21 “History,” he writes, has instead “proved the virtues of these elements to such a degree that … streets and squares constitute the very essence of the phenomenon ‘city.’”22

Yet if Gehl has recast the livable city as a timeless imprint of human scale (as if all that was needed was to simply rediscover it), he has simultaneously elevated the Homo sapiens’ biologically defined propensity to flock into a critical component of this urban agenda. In a particularly illuminating scene from The Human Scale (2012), a documentary movie celebrating Gehl’s work, footage of roads clogged with cars fades into a sample of his realized projects of pedestrian streets with suitably inoffensive planting and street furniture. Gehl’s vision of fewer cars and more people on streets is disarmingly simple, translating automatically as a recipe for vibrant urbanity—because if you congregate in cars, you create a traffic jam, not urban life.

The correspondence of street typology and the sensorimotor apparatus of Homo sapiens drives, consequently, the argument for pedestrianization as a ground for reviving urbanity in the livable city. In the words of Gehl, “Man was created to walk, and all of life’s events large and small develop when we walk among other people. ... But in cities there is so much more to walking than walking! There is direct contact between people and the surrounding community, fresh air, time outdoors, the free pleasures of life, experiences, information.”23 For if Homo sapiens’ dimensional parameters justified the street typology, then its gregarious nature has predestined it to become a pedestrian.

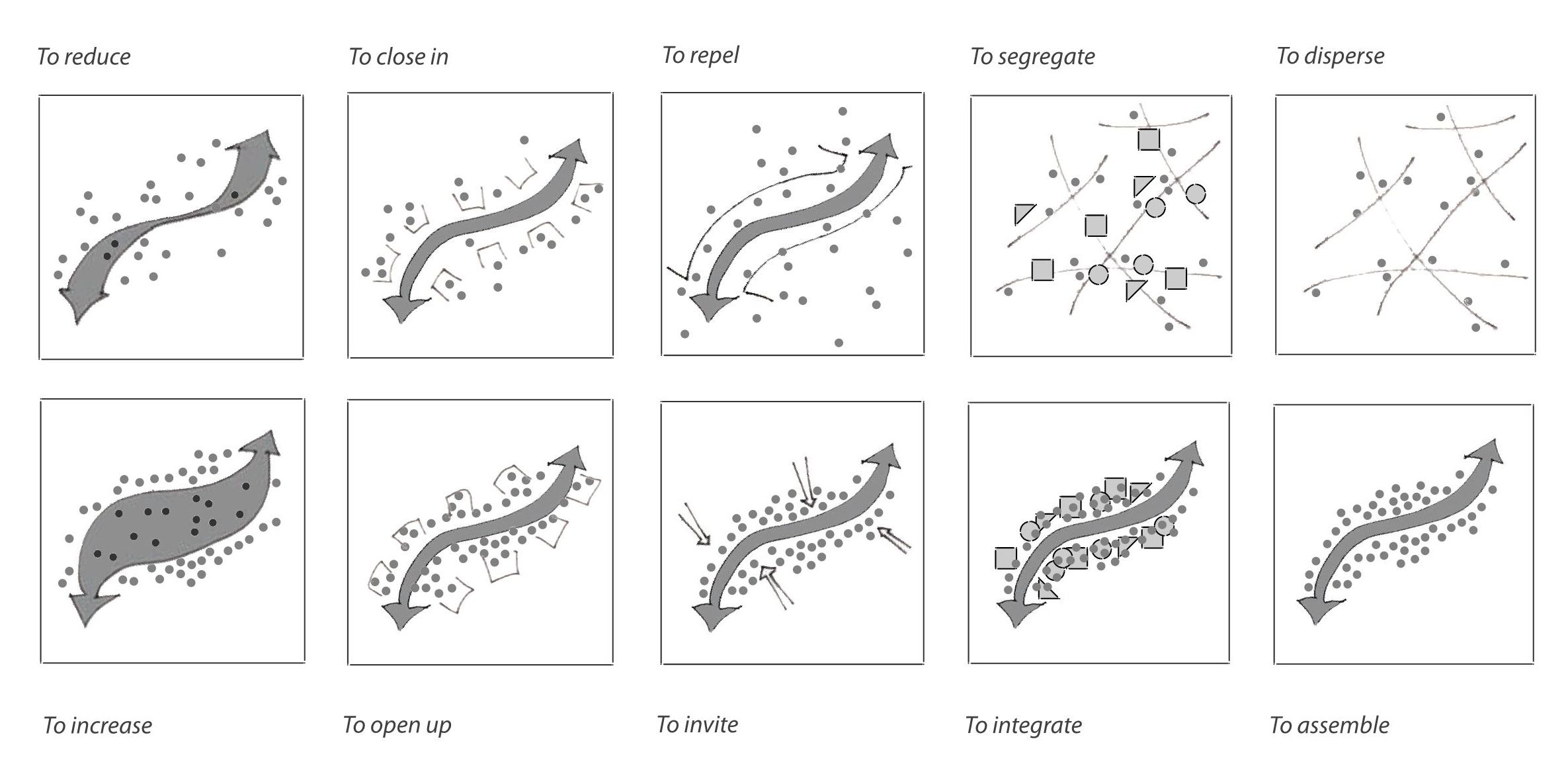

On account of redefining the citizen as a moving and gregarious animal, the ideal conditions for the flourishing of human life can be created by simply adjusting the physical formal parameters of the space between buildings. Gehl’s books read as authoritative texts for (re)creating this ideal habitat for Homo sapiens with checklists such as “12 quality criteria concerning the pedestrian landscape”24 or “5 rules for designing great cities,”25 and binary pairs such as invite or repel, integrate or segregate,26 and predictably enough, “people rather than cars.”27 There is a tangible glee with which Gehl rattles off the list of municipal clients he has worked with from Moscow to Singapore, Helsinki to São Paulo; the livable city is thus presented as one that transcends ideology, culture, race, and class.

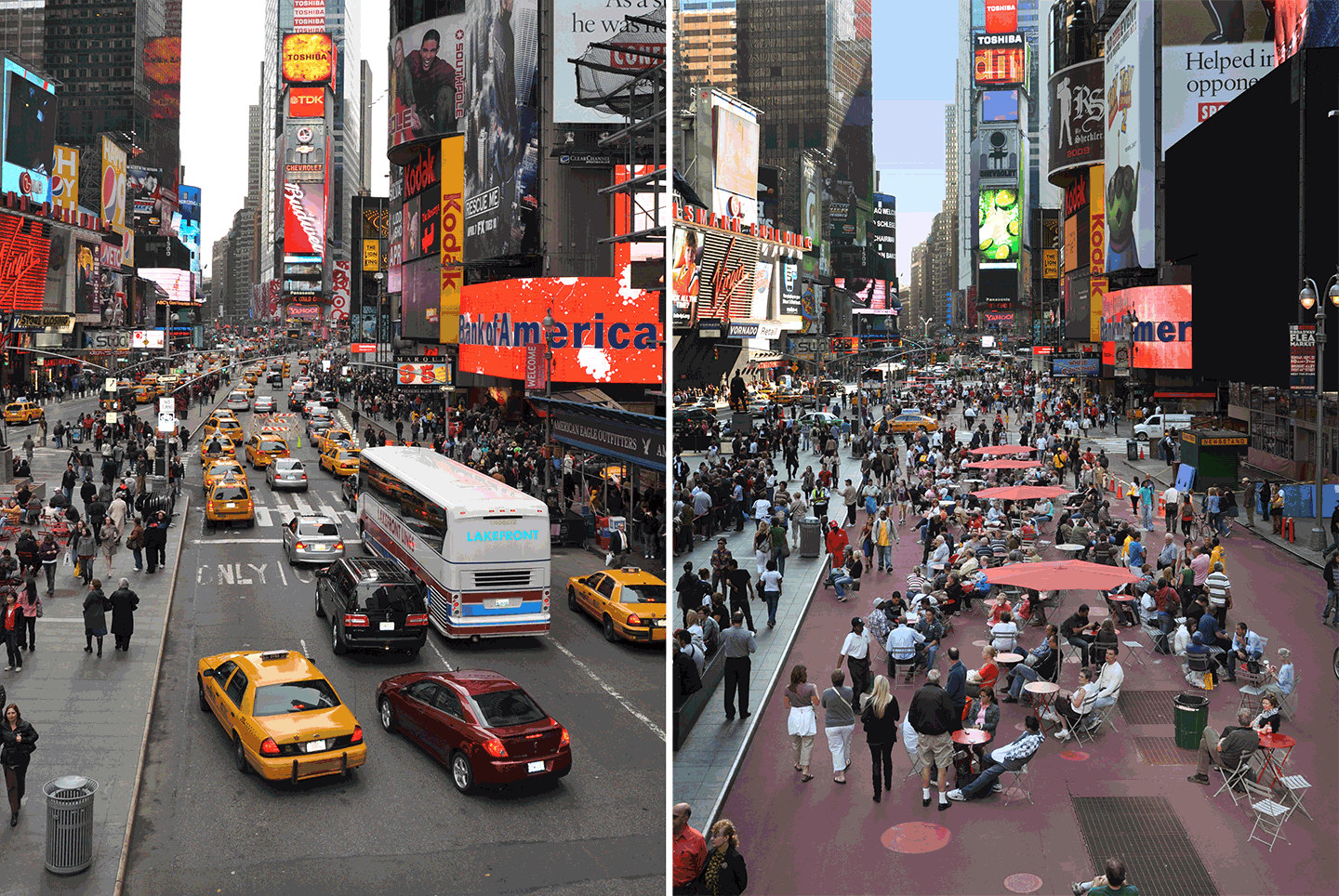

Gehl’s practice, does not define itself as a planning office but as an “urban quality consultant.” Established as a partnership between Gehl and his former student Helle Søholt in 2000, the office focuses less on traditionally defined urbanism than on reports, visions, and design studies on pedestrianization, leading to and improving ostensibly deficient, failing urban spaces. The office, for example, served as the main consultant on Michael Bloomberg’s PlaNYC initiated in 2007, brought on board to conduct their trademark Public Place/Public Life survey for the city. Applying behavioral observation and questioning techniques borrowed from psychology to the analysis of urban space, the survey was the opening salvo in Gehl’s mission to reclaim New York for “people,” providing figures on pedestrian traffic, demographics, and usage. It was followed by “1:1 pilot projects” that were eventually made permanent, such as the experiment with closing off Times Square to cars in 2007 leading to its pedestrianization in 2015. Observations such as “86 percent more people stop up—meet, sit down, talk or people watch—and 26 percent more leave their offices for breaks” reaffirmed this process through the very same survey techniques that initiated it in the first place.28

First undertaken in Copenhagen in the 1960s, Gehl’s Public Space/Public Life survey has evolved into a corporate service package. Its prestige has been secured by the story of the Danish capital’s gradual pedestrianization, paralleling its alleged rise to “the happiest city in the world.”29 The results produced from the survey are remarkably consistent across diverse cultural contexts and appear invariably in almost every urban project today. Whether this can be attributed to Gehl’s proclaimed universality of human behavior or to the survey’s schematic setup, the observations on overly dominant vehicular traffic networks, the lack of diversity in street-level zoning, and insufficient open “public” space have made tackling those same issues the chief concern of planners and politicians worldwide. Though one can speculate on the continued uncritical acceptance of Gehl’s work, there is a distinctly convenient alignment between his methodology and the challenges that take place at the highest levels of municipal planning and decision-making. Gehl’s studies, checklists, and easily repeatable mantras make it easy to relieve the burden of political decision-making fraught with democratic opposition and social inequality. Indeed, who would argue against making cities more lively and pedestrian-friendly?

Hygge Urbanism

Famously hands-off, Gehl travels the world as a brand ambassador of “cities for people,” lecturing against the technocracy of modern urbanism.30 It is perhaps then with a certain irony that Gehl himself hails from Denmark, where postwar modernism shaped the country’s progressive development of the Nordic welfare model. Much of the urban qualities that Gehl champions would not have been made possible without the progressive political and spatial values of Scandinavian modernism—the equality of opportunity, wealth redistribution, and public responsibility, the values on which the Nordic welfare state was founded. Faced with a migrant crisis, rapidly aging demographics, and enduring neoliberal reforms, this model appears more precarious than ever.

Symptomatic of these conditions is the recently popularized concept of hygge. Originating in Denmark, and globalizing as the country’s export brand, hygge aims for the creation of cozy and convivial atmospheres, promoting a life of quietude consisting of burning candles wrapped in woolly blankets. This word image has been more or less inadvertently transposed from a cultural trope to a socio-political model, sustaining the substitution of communitarian well-being for collective welfare.31 Critics of hygge have argued that its spread as a desirable form of being-togetherness forecloses difficult discussion and democratic agonism while accelerating social exclusion and xenophobia, as if to say “let’s just be hyggelig,” lest we disturb the convivial atmosphere.32

Herein lies the danger of the continued stigmatization of modernist urbanism as a mere technocratic folly. While the modernist city could at least lay claim to a belief in the emancipatory potential that industrialization and modern urbanization could hold for the working class, as in the case of German Siedlungen and European postwar housing programs, the livable city makes no such claim. Sustained by the rhetorical capacity to offload any and all urban problems onto a putative image of aberrant modernity, the livable city casts aside the history of diverse struggles for social equality in favor of a universalizing image of urban street “life.” The notion of public space by virtue of being accessible has become the self-fulfilling prophecy of livability. By appealing to the universal gregariousness of Homo sapiens, Gehl’s cities-for-people agenda effectively performs as a hygge urbanism—as any attempts to raise questions of gentrification or affordability can simply be cast aside as a matter of policymaking or structural problems in the market, foreclosing the political from urbanism itself. Moreover, reclaiming scraps of space in the pursuit of “cities for people” is then recast as progressive action in the face of market development. Yet in the single-minded pursuit and celebration of the life between buildings, what then of the life in buildings?

The Value of Livability

Discussions of the livable city inevitably turn on the promise of a win-win scenario: “people-centric” environments for diverse and flourishing urban life facilitating cities’ competitiveness and unlocking their populations’ entrepreneurial potentials. Livability therefore factors prominently in public decision making, with many an ambitious mayor seeking to raise the stock of their respective cities. Though many would acknowledge that livability is indeed a design complement (if not component) to the creative city, the copious evidence of the latter’s gentrifying effects has only bolstered a conviction that cities need to become livable nonetheless. There is an enduring sense that the pleasures of urbanity and pedestrianization are real in some immediately tangible way. Urban competitiveness is consequently staked on a broad consensus of livability, ostensibly absolved from the divisive implications of urban policies catering to more or less narrow segments of the creative class.33

That pedestrianization facilitates individual consumption would be nothing new in itself. From the writings of Kevin Lynch to the consulting practices of organizations such as Space Syntax, the championship of street has turned invariably onto its retailing potential.34 Manfredo Tafuri observed the same phenomenon playing out already in the nineteenth-century metropolis, with shopping arcades as places where crowds learned the “correct use of the city.”35 Today, however, the public of shopping pedestrians is no longer simply “an instrument of coordination of the production-distribution-consumption cycle,” as it was in pre-Fordist and Fordist capitalism.36 What is historically novel about the livable city is that the social itself has become productive from the perspectives of real estate capital and entrepreneurial municipalities that coalesce around the latter.

The social deepens the contradictions of Florida’s creativity, even as it consolidates them for a new round of urban accumulation. When mayors consult Jan Gehl, it is rather them, as it were, who are “shopping” for pedestrians, as a somewhat capricious yet still conveniently predictable polycephalous subject spawning an atmosphere of sociability, or so they hope—an atmosphere that functions as a cultural marker of centrality and ergo as an economic lever of real estate and landed capital, a fictitious form of valorizing potentialities percolating through these atmospheres. 3738 The livable city gives the creative city and real estate industry’s mantra “location, location, location” another turn of the screw by tying it to the gregarious behavior of Homo sapiens. If urban land values rise in the proximity of “nature,” as near Manhattan’s Central Park, then they are skyrocketing today near places “where it happens,” as near the High Line, with “it” simply standing for suitably innocuous forms of walking and sitting around—ideally with a cappuccino in hand, lest one appear as a creepy stalker disturbing the hyggelig urban atmosphere between buildings.

Homo Cappuccino

In a recent public talk, Gehl was adamant about the importance of cappuccino to urban livability: “Cappuccino is a pretext for sitting [and] having a good time in the city. You can just not sit in the city for three hours and pretend that you are not queer. If you just sit there, police will say ‘what are you sitting there for?’”39 As this deeply uncomfortable statement bespeaks, the livable city is a rampant normalization machine. Just as Michel Foucault observed that the making of Homo œconomicus through neoliberal governmentality entailed a particular form of subjectification, so, too, does the enlisting of Homo sapiens in the service of urbanism constitute a hegemonic “grid of intelligibility” through which urban subjects are produced.40 Indeed, as we have outlined here, if Homo sapiens’ sensorimotor qualities constitute the necessary condition of the livable city, then its complementary sufficient condition is this species’ gregarious nature. In the end, however, the subject of the livable city is not simply Homo sapiens, nor even that of Homo ludens for whom play was distinctly separate from ordinary life.41 The life promised by the livable city is rather the life of a nascent Homo cappuccino, a subject both consumer and producer—a prosumer of the lively atmosphere of streets and squares, for whom sociability appears as the categorical imperative.

In perhaps one of the most enduring quotations from Whatever Happened to Urbanism, Koolhaas concludes that “if there is to be a ‘new urbanism’ it will not be based on the twin fantasies of order and omnipotence; it will be the staging of uncertainty [and ...] the irrigation of territories with potential.”42 While the pundits of hooray urbanism appeal to the spontaneity and “potentials” of urban life, the outcome of such a project is far from uncertain. In instrumentalizing the social behavior of its users, the livable city is fundamentally a form of governmentality that promises nothing less than the full extraction of the potential of Homo cappuccino.

We certainly do not intend to criticize Homo cappuccino on moral and individual grounds, likely only to further the cultural-conservative critique of Homo œconomicus while obscuring the way in which this subject has been institutionally and intellectually produced. Rather, our contention is that designerly sensibilities for the presence of Homo cappuccino belie an internal rift within that caffeinated species itself. It is a rift that opens between the precarious and upwardly mobile, as well as within the anxious subjectivities of precarious “dividuals” themselves—internalizing rather than overcoming the ambiguities of the creative city policies. While the livable city is complicit in the poverty of citizens who can’t afford to promenade and sip cappuccinos, it lives off the labor of an increasingly precarious class of urban dwellers.

The urbanity of the livable city, produced, consumed, and produced again requires the active participation of Homo cappuccino as a distinct type of unwaged surplus labor. The “immaterial” labor of animating urban atmospheres and galvanizing real estate value, appropriated without any compensation, nor even allocation for subsistence, has thus been brought forth by the livable city in an unmistakably tangible way. Faced with austerity, unaffordable housing, and rising debt, responding with wider sidewalks and bicycle lanes becomes so banal that it is almost insulting. While the cappuccino surely goes along with conversations and being social, its emphasis also leads to politically despondent phenomena such as latte art and other Instagrammable diversions. “In the dismantled … welfare state,” wrote the journalist Gabriella Håkansson, “the only thing that has happened is that more coffee shops have opened.”43

The Neoliberal Social

The early neoliberal critique attacked the “social,” claiming it was incompatible with free markets. For Friedrich Hayek this term was “a parasitic fungus of a word” and a cause of “the general degeneration of moral sense in the world.”44 It is then a bitter irony that the social has been more recently revived from within a neoliberal governmentality as a putative marker of its distinction from individualistic and materialistic economy, and as “something which can be quantified, nudged, mined and probed.”45 The term’s revival has coincided with the rise of sharing economy and social media and consequently with what Michel Feher described as an imperative of self-appreciation.46 Unlike his utilitarian counterpart maximizing individual satisfaction and profit, the neoliberal Homo œconomicus measures its value in terms of worth and potentials. The social is then the environment of his esteemed worth.

What then does livability hold for Homo cappuccino? We can interpret the livable city as a tangible complement to platform capitalism, where the social is produced under the guise of a hygge urbanism.47 Livability appears so seductive to municipalities around the world because it promises to facilitate an atmosphere of urbanity, conveying a spontaneously unfolding everyday urban life. Such an approach is embraced as more ethical, because it is ostensibly less about maximizing returns on investment and more about appreciating the stock value of their respective cities, a docile norm conforming to the body of Homo Cappuccino. The role of the latter, as the main protagonist of the livable city, is to conduct itself as a living proof that cities are for people. Yet if Homo cappuccino has been cherished as the active agent of appreciating real estate values—a foam, as it were, atop the lively pedestrian brew—any and all concerns for the imperative of self-appreciation imputed to this protagonist herself have been discarded.

To remake the life between buildings for people is therefore less of a humanistic remainder to arguably technocratic forms of neoliberal governmentality, than a full-fledged component of its most recent iteration. The speculative valorization of the social is not simply a form of “pacification by cappuccino,” nor is it reducible to the concept of gentrification as an immediate monetization of rent gaps to their highest and best use. 4849 While these processes surely continue to structure uneven urban development, the livable city is now superimposed on them as a cunning mediator between people and finance, giving us a trinity of Homo sapiens, Homo œconomicus, and Homo cappuccino. By addressing only life between buildings, and only in terms of people-centric design, livability extracts the intense flavors of Homo cappuccino even as it renders ordinary life inside buildings irrelevant to urbanism, intractable to urban policies, and inaccessible to ever larger numbers of people.

As powerful as an ideal the right to the city has become, its progressive potential may now have reached a limit of efficacy.50 On the one hand, it has been appropriated by politically neutered slogans such as “the right to space,” as well as the good intentions of bottom up, participatory spectacles.51 While on the other, governments and municipal decision makers, concerned primarily with making their cities livable, and ergo potentially competitive and worthy of investment, invariably acquiesce to the demands of the market, fearful, for good reason, of a declining credit rating.

However, there is an undeniable pressure with which to confront the vision of the livable city today. As fewer can afford to live in the city, the very image of livability comes under threat as well. As the case of Richard Florida illuminates, the survival of the neoliberal city now paradoxically depends on ostensibly social democratic and socialist policies, such as affordable housing provision.52 Might then the livable city, in bringing the value of urbanity forward in such a direct way, offer new tactical opportunities at the scale of the city itself, or should it be challenged in more strategically direct ways? At the very least, if there is to be a new urbanism, it may well not be one of order and omnipotence, but it will also need to be one that no longer surrenders itself to the spontaneity of urban life.

-

Rem Koolhaas, “What Ever Happened to Urbanism?” in Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, S, M, L, XL (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1995), 958–971, 963. ↩

-

Al Gore, “Remarks as Prepared for Delivery by Vice President Al Gore,” speech at the American Institute of Architects, January 11, 1999, link. ↩

-

Jan Gehl, Cities for People (Washington: Island Press, 2010). Published with a preface by Richard Rogers. ↩

-

Jan Gehl, Life between Buildings (Washington: Island Press, 2011). The appearance of Life between Buildings in Danish coincided with the publication of the psychological investigation of the urban living environment by his wife. See Ingrid Gehl, Bo-Miljø (Copenhagen: Statens byggeforskningsinstitut, 1971). Life between Buildings was translated to English in 1987. In 2011, the seventh revised edition was published. ↩

-

We adopt this expression from Ernst Bloch’s term “hurrapantheistich,” which he used to describe the neo-vitalist philosophy of Hans Driesch. Erns Bloch, “Über Naturbilder seit Ausgange des 19. Jahrhunderts,” in Literarische Aufsätze, vol. 9 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1985): 456. Thanks to Sandra Jasper for the reference. ↩

-

Edward Glaeser, Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier (Penguin Books, 2011); Richard Florida, Cities and the Creative Class (Routledge, 2005); Jeff Speck, City 2.0: The Habitat of the Future and How to Get There (TED Books, 2013); Charles Montgomery, Happy City: Transforming Our Lives through Urban Design (Penguin Books, 2015). ↩

-

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961), 18. ↩

-

Jacobs drew on the cybernetic classic Warren Weaver, “Science and Complexity,” American Scientist 36 (1948): 536–544. ↩

-

Brian Tochterman, “Theorizing Neoliberal Urban Development. A Genealogy from Richard Florida to Jane Jacobs,” Radical History Review 112 (2012): 65–87. ↩

-

Richard Florida, Cities and the Creative Class (Routledge, 2005), 139. ↩

-

Florida, Cities and the Creative Class, 4. ↩

-

Florida, Cities and the Creative Class, 22. ↩

-

Richard Florida, The New Urban Crisis (New York: Basic Books, 2017). ↩

-

On the debate, see Sam Wetherell, “Richard Florida Is Sorry,” Jacobin, August 19, 2017, link; Cardiff Garcia, “Richard Florida on Geographic Inequality,” Financial Times, October 13, 2017, link, where Florida says: “It’s not a mea culpa and I’m not sorry”; Oliver Wainwright, “‘Everything Is Gentrification Now’: But Richard Florida Isn’t Sorry,” The Guardian, October 26, 2017, link. ↩

-

Florida, The New Urban Crisis. ↩

-

Gehl, in Andreas Dalsgaard (director), The Human Scale (Denmark: Final Cut for Real, 2012), 02:12. ↩

-

Gehl’s interest in Jane Jacobs is characteristically limited to The Death and Life of Great American Cities, unlike Florida who draws also on her Economy of Cities and Cities and the Wealth of Nations. ↩

-

Gehl, Life between Buildings, 87. The work of Krier represents for Gehl an “interesting renaissance of the proven principles of cities built around streets and squares,” Gehl, Life between Buildings, 89. Even as postmodern neo-classicists attacked the universality of modernism they came forth with their own version. Léon Krier hoped to reground the discipline in “universal human principles which have provided architecture’s foundation for thousands of years.” Krier, cited in Joan Ockman, “The Most Interesting Form of Lie,” in K. Michael Hays, Oppositions Reader: Selected Readings from a Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture, 1973–1984 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 412–21, 414. ↩

-

Gehl, Cities for People, 33. ↩

-

See Maria Giudici, The Street as a Project. The Space of the City and the Construction of the Modern Subject (PhD diss., TU Delft, 2014). ↩

-

Gehl, Life between Buildings, 89. The change is consequently conceived as the realignment of cities and “human nature,” a change undoing the modernist change. Cf. the following argument of Victor Papanek: “[W]e find beauty in design only when it is compatible with forms and processes in nature. Human beings must learn more about what the world is really like and spend less time dreaming about the kind of world they would like it to be if they could only change it.” Victor Papanek, Design for Human Scale (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1983), 146. ↩

-

Gehl, Cities for People, 19. ↩

-

Gehl, Cities for People, 239. ↩

-

Constanza Martínez Gaete, “Jan Gehl’s 5 Rules for Designing Great Cities,” ArchDaily, December 16, 2016, link. ↩

-

Gehl, Life between Buildings, 113 and 101. ↩

-

Gehl, Cities for People, 13. ↩

-

Cited in “Unrolling a Welcome Mat for the People of New York,” Gehl, link. In a similar pilot project in San Francisco, it was observed that “the number of people engaged in lingering activities such as standing, waiting for transport, bench sitting, and playing increased by an average of 55 percent on weekdays and 176 percent on weekends—even reaching a high of 700 percent.” Cited in “Prototyping on Market Street,” Gehl Institute, link. ↩

-

Michael Booth, “Copenhagen: The Happy Capital,” The Guardian, January 24, 2014, link. ↩

-

Notably, Gehl’s website lists Jan Gehl as a “founder and senior advisor” rather than a partner. ↩

-

William Davies, “The Emerging Neocommunitarianism,” the Political Quarterly, vol. 83, no. 4 (2012): 767–776. ↩

-

Charlotte Higgins, “The Hygge Conspiracy,” The Guardian, November 22, 2016, link. ↩

-

This model of reasoning has a conspicuous presence in the history of humanistic urbanism. “One may...criticize the historic preservation movement...that it too often displaces the people who live in the areas about to be restored,” wrote Kevin Lynch in 1981, only to remarkably maintain that “class-based as it may presently be...the pleasures of restoration are real...[and] can provide economic benefits.” Kevin Lynch, A Theory of Good City Form (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1981), 259. ↩

-

Lynch noted that “spontaneous or accidental communication (‘Oh, look at that fur coat in the window!’), which is one of the advantages of present city life, might be impaired by the lack of concentration.” Kevin Lynch, “The pattern of the metropolis,” Daedalus, vol. 90, no. 1 (1961): 79–98, 83. ↩

-

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976), 84. ↩

-

Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia, 83. ↩

-

On the politics of “urban atmospheres” more broadly, see Matthew Gandy, “Urban Atmospheres,” Cultural Geographies, vol. 24, no. 3 (2017): 353–374. ↩

-

David Harvey, The Limits to Capital (Oxford: Basil Blackwell), 367–372. Anne Haila helpfully clarified that this capital is fictitious as a “claim over future revenue” but also “in the sense of breaking the connection to the use of land.” With its securitization, according to Haila, land and real estate has become not only fictitious capital but a fictitious financial investment. Anne Haila, Urban Land Rent: Singapore as a Property State (London: Wiley, 2015), 60 and 210. ↩

-

Jan Gehl, “Livable Cities in the 21st Century,” lecture at the Aalto University, Helsinki, February 21, 2017, link, 43:10. ↩

-

To quote Foucault at length here: “The subject is considered only as homo œconomicus, which does not mean that the whole subject is considered as homo œconomicus. In other words, considering the subject as homo œconomicus does not imply an anthropological identification of any behavior whatsoever with economic behavior. It simply means that economic behavior is the grid of intelligibility one will adopt on the behavior of a new individual.” Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College de France 1978–79 (New York: Palgrave, 2008), 252. ↩

-

Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1955). ↩

-

Koolhaas, “What Ever...,” 969, our emphasis. ↩

-

Gabriella Håkansson, cited in Jakob Norberg, “No Coffee,” Eurozine, August 8, 2007, link. ↩

-

Friedrich Hayek, “What Is Social, What Does It Mean?” in Freedom and Serfdom. Anthology of Western Thought, ed. Albert Hunold (Dordrecht: Reidel, 1961), 107–118, 114. ↩

-

Will Davies, “The Chronic Social: Relations of Control within and without Neoliberalism,” New Formations: a Journal of Culture/Theory/Politics 84–85 (2015): 40–57, 54. See also Will Davies, The Happiness Industry (London: Verso, 2016), 181–197. The recent award of the Nobel Prize for Economics to Richard Thaler, the author with Cass Sunstein of Nudge, is the latest evidence of the neoliberalization of the social. ↩

-

Michel Feher, “Self-appreciation; or, the Aspirations of Human Capital,” Public Culture, vol. 21, no. 1 (2009): 21–41. ↩

-

Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2017). ↩

-

Sharon Zukin, The Cultures of Cities (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), 28. ↩

-

The consumption-side theory of gentrification has been criticized (correctly, we believe) for ignoring the role of capital investments and rent gaps in gentrification. See Neil Smith, “Toward a Theory of Gentrification. A Back to the City Movement by Capital, Not People,” Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 45, no. 4 (1979): 538–548. Yet urban livability and Homo cappuccino, to paraphrase Smith, represent “a back to the city movement by capital under the guise of cities for people.” ↩

-

David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” New Left Review 53 (2008): 23–40; Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City,” in Writing on Cities (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), 147–159. ↩

-

See the Danish Pavilion at the Venice Architectural Biennale 2016, dedicated to the work of Jan Gehl, titled “Art of Many—the Right to Space.” The “right to the city” has been simultaneously co-opted by “hooray” urbanists of the ubiquitous computing type. See Carlo Ratti, Matthew Claudel, The City of Tomorrow: Sensors, Networks, Hackers, and the Future of Urban Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 146–7. ↩

-

Recent experiments with universal basic income, such as the one in Finland, represent the same conspicuous paradox at a different scale, the politics of equality sanctioned by galvanizing the entrepreneurial potential of human capital. ↩

Maroš Krivý is a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Geography (ERC project “Rethinking Urban Nature”) and chairs the master’s program in Urban Studies at the Faculty of Architecture, Estonian Academy of Arts. He is the author of “Towards a Critique of Cybernetic Urbanism” (Planning Theory, 2016), “Postmodernism or Socialist Realism?” (JSAH, 2016), and “Greyness and Colour Desires” (JoA, 2015), and published in journals such as Footprint, Scapegoat, City, and IJURR.

Leonard Ma is a Canadian architect based in Helsinki; he is a teacher at the New Academy.