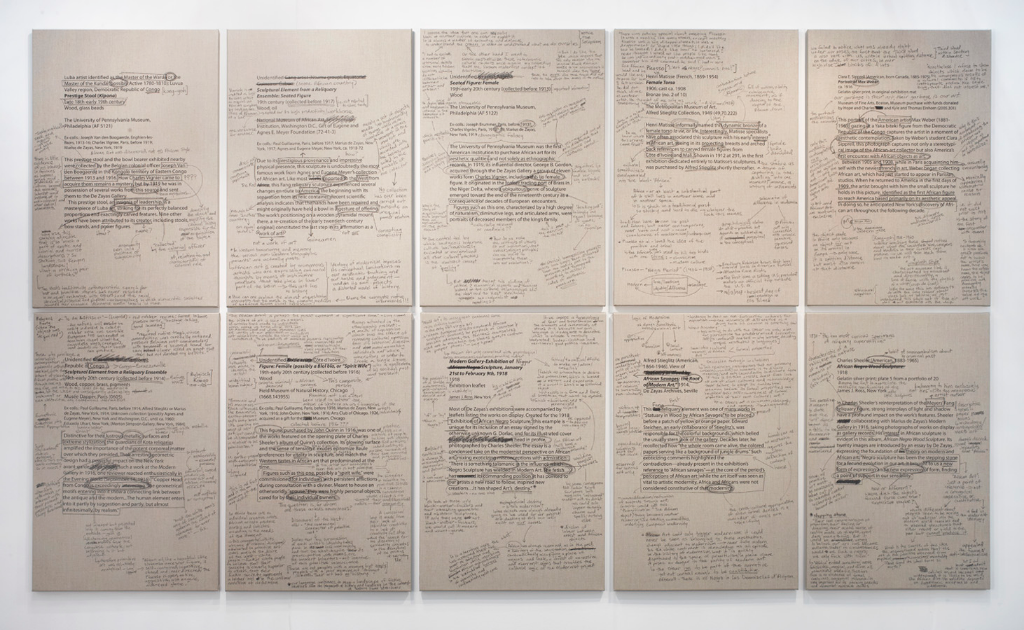

While visiting the Studio Museum in Harlem one very cold winter day in February, I wandered into an exhibition titled Excerpt that examined the use of language as a form of resistance. I was immediately struck by one of the installations, “Wall of Casbah.” The piece was created by Botswana-born artist Meleko Mokgosi, whose work explores and deconstructs the ways in which European notions of national identity and race—often colonial in origin—still define our understandings of history and subjectivity. In “Wall of Casbah,” Mokgosi takes as his subject a series of museum labels from the 2009 Getty Museum exhibition, Walls of Algiers: Narratives of the City. Through acts of annotation—marking, crossing out, and commenting on the artwork under consideration—similar to that of condition reports produced by museum curators and registrars, Mokgosi contends with the banality of colonial discourse in the descriptive and didactic labels that shape our understanding of works of art. One of Mokgosi’s labels uses Le Corbusier’s “Sketches for the Redesign of Algiers” as a starting point to address and critique the architect’s “problematic imperial narratives regarding indigenous and settler populations.” The installation forces viewers to confront the injustices of colonialism, and of other oppressive institutions, as well as the centuries of harm inflicted upon many through urban design policy. This type of dual resistance—against both racial injustice and urban design—is emerging not only from artists but from community development practitioners, journalists, and academic theorists.

In the wake of Donald Trump’s election to the American presidency, community development activists have used social media to call on their peers to resist his administration’s infrastructure plans, including the wall along the US–Mexico border. Many AIA members condemned their CEO Robert Ivy’s warm embrace of the newly elected president and threatened to withhold membership dues.1 But one has to wonder where these voices have been while federal laws and municipal policies left many urban neighborhoods crippled and underserved for almost a century. Or, more currently, what have they done to help combat “problematic imperial narratives regarding indigenous and settler populations,” to use Mokgosi’s words again?2 Are the design professionals who demand resistance to President Trump’s infrastructure agenda willing to respond to the many marginalized communities that have been resisting racism and inequality for tens, if not hundreds, of years?

I am an African American community development practitioner who works in low-wage, predominantly African American neighborhoods in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I grew up in Harlem and currently live in the Hill District of Pittsburgh, both historically African American neighborhoods. It is not difficult for me to identify with Mokgosi’s desire to critique “European notions of representation in order to address questions of nationhood, anti-colonial sentiments, and the perception of historicized events.”3 Within the American context, the mythology of discovery and invention play vital roles in architecture and design in urban places.

Placemaking: The Resistance

In the early twentieth century, African Americans migrated to urban areas fleeing racial terrorism in rural, mostly southern states and searching for employment in northern industrial cities. The introduction of racially divisive legal interventions such as zoning, redlining, and restrictive covenants led to the concentration of African American residents into specific urban neighborhoods. As a result, African Americans were forced to reinvent their understanding of space and their presence in the public domain. In reshaping the spatial identity of Harlem, the neighborhood was recast as a sanctuary for hundreds of thousands of African diasporans within and outside the United States. It is still recognized as the center of black American culture. Now, many neighborhood residents feel the nearly one hundred years of collective African American social, cultural, and economic investment in Harlem is in danger of being sold off.

Since the mid-1980s Harlem’s predominantly African American residents have been resisting activity they feel is designed to displace them. In 1985 a group of residents protested the groundbreaking of Towers on the Park, a housing development at 110th Street and Central Park West, declaring that the development was an effort to gentrify the neighborhood.4 More recently, a longtime Harlem resident and close friend attended a Community Board meeting (a City of New York–sanctioned advisory panel that makes land use and zoning recommendations to government officials). According to his account, during the public comment segment of the meeting, several neighborhood residents vehemently pushed back against the proposal to rename the southernmost section of west Harlem, “SoHa.” Over the last decade, real estate agents have renewed their previous attempts to create a marketable “sense of place” in specific sections of Harlem—a practice that speaks to the long struggle over neighborhood naming rights and has resulted in many of the now familiar neighborhoods in New York, the “invention” of Park Slope and the renaming of Hell’s Kitchen among them. A journalist later described the residents’ hostility in this way:

My friend was initially taken aback by the resistance. He hadn’t anticipated such a visceral reaction by residents: “neighborhoods morph and change.” But “by the same token,” he pondered, “the process of naming a neighborhood is not organic if you have an established neighborhood already and an outsider is trying to rename it to serve their goals.” Rather it is a process intended to provide commercial value to new people moving into the neighborhood, not for the people already there.

In Harlem the concept of placemaking is being put into practice. As a community development practitioner I’ve always understood it as a tool to provide greater opportunities for outside forces in architecture, urban design, and real estate development that were rarely made available for existing residents—a type of urbanism that has been sometimes categorized in its most opportunistic forms as “white people commercial hijinks.”5

Placemaking: The Destruction of Memory

Architecture plays an essential role in ordering physical space and in reflecting cultural identity. Over the centuries, as the discipline evolved, urban planning and design professionals have created a lexicon to describe and formalize practices within the built environment. Many of these interventions have been designed to maintain order in an ever-evolving physical landscape of places, usually reflecting the shared cultural identity and social values of the most privileged and powerful classes. Over time it has become more and more vital for people who live in neighborhoods like Harlem to protect the cultural and aesthetic significance of the many historical and social values there by preserving the neighborhoods’ architecture.

War has long been a metaphor for contested urban development. The destruction of architecture is often not simply a consequence of battle but rather the purposeful erasure of an enemy’s culture. In The Destruction of Memory, Robert Bevan observes that physical sites are eliminated with the intention of erasing the cultural and social significance given to them.6 Architecture is destroyed during war as a means of “dominating, terrorizing, dividing or eradicating altogether” the culture of a nation. Both a process and a philosophy, placemaking fits into this logic by capitalizing on a local community’s assets and inspiration, with the intention of first erasing, then creating spaces to promote the public health, happiness, and well-being of the newly arriving inhabitants.

Placemaking: America’s “Pioneering Spirit”

The term “placemaking” is an unfortunate portmanteau that, to many, is linked to “Christopher Columbus Syndrome,” a term made popular by film director and then Fort Greene, Brooklyn, resident Spike Lee. In a 2014 talk at Pratt Institute, Lee famously compared the arrival of white residents to this once predominantly black neighborhood to the first white settlers from the Old World arriving to the United States and extinguishing the existence of native populations—a trope that has been often used in discussing the social violence of gentrification. He suggests that, like the early settlers, newly arriving white residents disrupt decades of social and cultural codes established by existing black residents with the intent of establishing new ones.7 It is a concept created by an alliance between real estate interests and city government with the mission of “creating something out of nothing”—to manufacture value on otherwise undervalued spaces for profitable development. Over time, though, creating that “something” involves negating the existence of marginalized communities. Aspects of placemaking are perceived by some as the desire to “build utopia” on the ruins of another culture’s past.8 Thus placemaking has become an ill-defined buzzword that “most often serves to rally support for redevelopment projects that ignore deep patterns of local culture,” in the words of architectural historian and critic B. D. Wortham-Galvin. Others have argued that representations of culture and the image of an “ethnic enclave” are equally potent resources for exploitation in the making of developmental placemaking projects.9 “Advocating for sense of place may sound laudable,” Wortham-Galvin continues, “but it often implies the eradication of urban fabric or the displacement of residents deemed unsuitable for newly conceived places…are there places that are anything but remade?”10

There is certainly merit for remaking places. But community development professionals must acknowledge and address the reality that many African American and Latino populations have been remaking spaces throughout the urban landscape for decades following white flight. These subtler forms of placemaking often resist the forms of representation that are most familiar to the practices of real estate development and urban design.

African American and Hispanic residents survived decades of abandonment by elected officials, government agencies, and their fellow white residents. In many African American and Latino neighborhoods throughout New York City, residents cleared vacant lots to play stickball, grow farms, repair cars, and install art, epitomizing the social and economic realities of a struggling place destined to define itself. The absence of city resources is overcome by the creation of collective goals, dialog, negotiation, and reinvention. In the end, this lack of resources becomes the primary resource.11 Resilience and creativity emerge in an attempt to claim abandoned space and create new spaces founded by shared history and culture. When ignored by the authorities, communities are forced to utilize available resources, both physical and mental. Take informal taxis for example, often referred to as “gypsy cabs” or “jitneys,” which were established in marginalized neighborhoods to serve residents in response to a lack of formal taxi service in the area. However, these processes are marked by a constant friction between formal systems and unsanctioned activities.12

As a child, while visiting my cousins in the South Bronx, we played in “the lots,” the vacant parcels underneath the abandoned rail trestle near their home. We hunted for “treasure” among debris either left behind or intentionally dumped. As a teenager, I remember walking along Frederick Douglass Boulevard in Harlem and seeing a three-story-high basketball hoop, an art installation titled “Higher Goals” by the African American artist David Hammons. In a 2001 interview with the New York Times, Hammond, an Illinois native who spent the 1970s and 1980s in Harlem, bluntly declared “Harlem is under attack. White folks want it back.”13

Many residents in Harlem and neighborhoods like it share this sentiment. They feel that the very people who designed and built the suburbs in the 1950s–1980s to escape the decaying city—leaving poor communities of color to deal with it—are returning to reimagine the very spaces and people they abandoned. A “back to the city” movement motivated not by the desire to live among more ethnically diverse neighbors but rather by more economical and self-serving interests. Longing to flee the sterile confines of the suburbs, whites saw the urban environment as an opportunity to obtain more affordable housing and to be closer to work and the amenities surrounding it. There is a fear, accompanied by a growing resistance, that new and returning residents will attempt to remake these places in their own image.14 This desire to reimagine is historical. Wortham-Galvin writes:

After the adrenaline of the Revolution had worn off, Americans turned toward the crafting of a national identity. In a country founded in tabula rasa conditions (if one ignores, as the colonists did, the displacement of millions of Native Americans) the reconstruction of a common past was a logical step. Socially useful myths about the founding of the country were needed to adhere the new (white, land-owning) citizens to one another culturally and politically.15

Mythical placemaking is closely tied to American nativism or “ethno-nationalism,” which was originally constructed around racial superiority of whites over indigenous populations and (enslaved and free) people of African descent.16 This justified disqualifying those two groups from enjoying the privileges of democracy, thus denying them a place in shaping an “American” identity. What it means to be an American has always been closely tied to what it means to be white. Over time, the ideological and social construct of America seemed to evolve from an exclusively European identity:

The nations of the world, almost without exception, were formed from ethnic cores, whose pre-modern myth–symbol complex furnished the material for the construction of the modern nation’s boundary symbols and civil religion…. In the case of the United States, the national ethnic group was AngloAmerican Protestant (“American”). This was the first European group to “imagine” the [territory] of the United States as its homeland and traces its genealogy back to New World colonists who rebelled against their mother country. In its mind, the American nation-state, its land, its history, its mission, and its Anglo-American people were woven into one great tapestry of the imagination. This social construction considered the United States to be founded by the “Americans,” who thereby had title to the land and the mandate to mould the nation (and any immigrants who might enter it) in their own Anglo-Saxon, Protestant self-image.17

Upon their arrival to the New World, Anglo-American settlers seized land from its existing occupants. Branded as savages and barbarians, indigenous populations were deemed ill-equipped to put the land into productive use.18 Land was seen as a natural resource to be conquered, tamed, and properly developed for material gain. The indigenous populations were simply unable to realize the value of the environment they occupied, thus forfeiting any legitimate title to it.

In many ways, “placemaking” is intuitive to populations that are voluntarily resettling, a way of recreating space in order to inhabit it on their own terms. Early white American pioneers feared, yet romanticized, and finally conquered the western wilderness. White suburbanites fear, disparage, and yet seek to tame urban spaces for their own pursuits. The white middle class invasion into poor white, black, and brown spaces brings a legitimacy—social, economic, and cultural value—that current inhabitants are not interested, nor equipped, to provide. Neil Smith best describes this act of resettlement as revanchist, a brutal reclamation of space that was stolen by people who are characterized as inferior based on socioeconomic and/or racial status.19

We are witnessing a wave of displacement of African Americans from the places they created to escape the very physical and emotional harm they experienced a century before. Urban planning and development policies and practices that rely on placemaking and rebranding as strategies, accompanied by increasingly heavy-handed tactics of law enforcement, mean an urban frontier habitable only for those who are told they have an inherent right to it.

Design Justice

If urban design and community development practitioners are interested in resistance, we must reckon with the past in order to avoid repeating it. Some of the earliest condemnations of the AIA’s embrace of President-elect Trump have come from African American members like Brian Lee Jr., who helped coordinate Design as Protest, a day of action that brought together urban design practitioners and community activists across the nation. Another vital voice has been the Design Justice Network, which established a “living document” aimed at codifying “a socially and environmentally just code of ethics for operating as designers of the built environment.”20 Initiatives like these ask that we honor existing places, exercise empathy for existing communities, and cultivate an appreciation for activities that reflect the cultural and historic significance of existing spaces. One great way to start is to remove the word “placemaking” from the urban design lexicon.

-

Nicholas Korody, Amelia Taylor-Hochberg, and Paul Petrunia, “Architects Respond to the AIA’s Statement in Support of President-Elect Donald Trump,” Archinect, November 14, 2016, link. See also the Architecture Lobby, “A Response to AIA Values,” the Avery Review 23 (April 2017), link. ↩

-

Panel from “Walls of Casbah 2010–2012,” Excerpt, Studio Museum in Harlem, link. ↩

-

Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (London: Routledge, 1996), 161.

The name is supposed to identify a “trendy” southern part of Central Harlem, à la SoHo. The only problem is, it doesn’t exist. At least according to longtime residents and the local community board. Danni Tyson, a real estate broker and a member of Manhattan Community Board 10, which covers Central Harlem, says the move is “pretty arrogant.” “I totally disagree with it,” said Tyson. “To me, personally, it’s like trying to take the black out of Harlem. Harlem is Harlem.” Tyson said when she says she’s from Harlem people “know it exactly what it stands for.” But, SoHa? “It’s not something longtime residents use,” she said.[^5]

-

This is based on a conversation I had with a friend, who had made a post-election decision to become more politically active in Harlem, a neighborhood where he was born, raised, and currently resides. Attending the community board meeting in his council district was his first venture into some of the more formal real estate development and urban planning processes that occur at the neighborhood level. ↩

-

Robert Bevan, The Destruction of Memory (London: Reaktion Books 2016), 42. ↩

-

Joe Coscarelli, “Spike Lee’s Amazing Rant Against Gentrification: ‘We Been Here!’” New York Magazine, February 25, 2014, link. ↩

-

Bevan, The Destruction of Memory, 52. ↩

-

For more on this, see Arlene Dávila, Barrio Dreams: Puerto Ricans, Latinos, and the Neoliberal City (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004). ↩

-

B. D. Wortham-Galvin, “Mythologies of Placemaking,” Places (June 2008), link. ↩

-

Ivan Nasution, “Urban Appropriation: Creativity in Marginalization,” from the Fifth Arte-Polis International Conference and Workshop, “Reflections on Creativity: Public Engagement and the Making of Place,” August 8–9, 2014, in Bandung, Indonesia; proceedings published in Social and Behavioral Sciences 184 (May 2015): 4–12. ↩

-

Nasution, “Urban Appropriation.” ↩

-

Deborah Solomon, “The Downtowning of Uptown,” the New York Times, August 19, 2001, link. ↩

-

Lance Freeman and Tiancheng Cai, “White Entry into Black Neighborhoods: Advent of a New Era?” in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 660, no.1 (June 2015): 302. ↩

-

Wortham-Galvin, “Mythologies of Placemaking.” ↩

-

Eric Kaufmann, “American Exceptionalism Reconsidered: Anglo-Saxon Ethnogenisis in the ‘Universal’ Nation, 1776–1850,” Journal of American Studies, vol. 33, no.3 (December 1999). ↩

-

Kaufmann, “American Exceptionalism Reconsidered.” ↩

-

Nancy Isenberg, White Trash: The 400-Year Untold Story of Class in America (New York: Viking, 2016), 18–19. ↩

-

Smith, The New Urban Frontier, 207–211. ↩

Karen Abrams is a native Harlemite, living and working as an urban planner in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is currently a Loeb Fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.