We recognized that in order to bring the people to the level of consciousness where they would seize the time, it would be necessary to serve their interests in survival by developing programs which would help them to meet their daily needs…these programs satisfy the deep needs of the community but they are not solutions to our problem. That is why we call them survival programs, meaning survival pending revolution.

— Huey P. Newton, To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton1

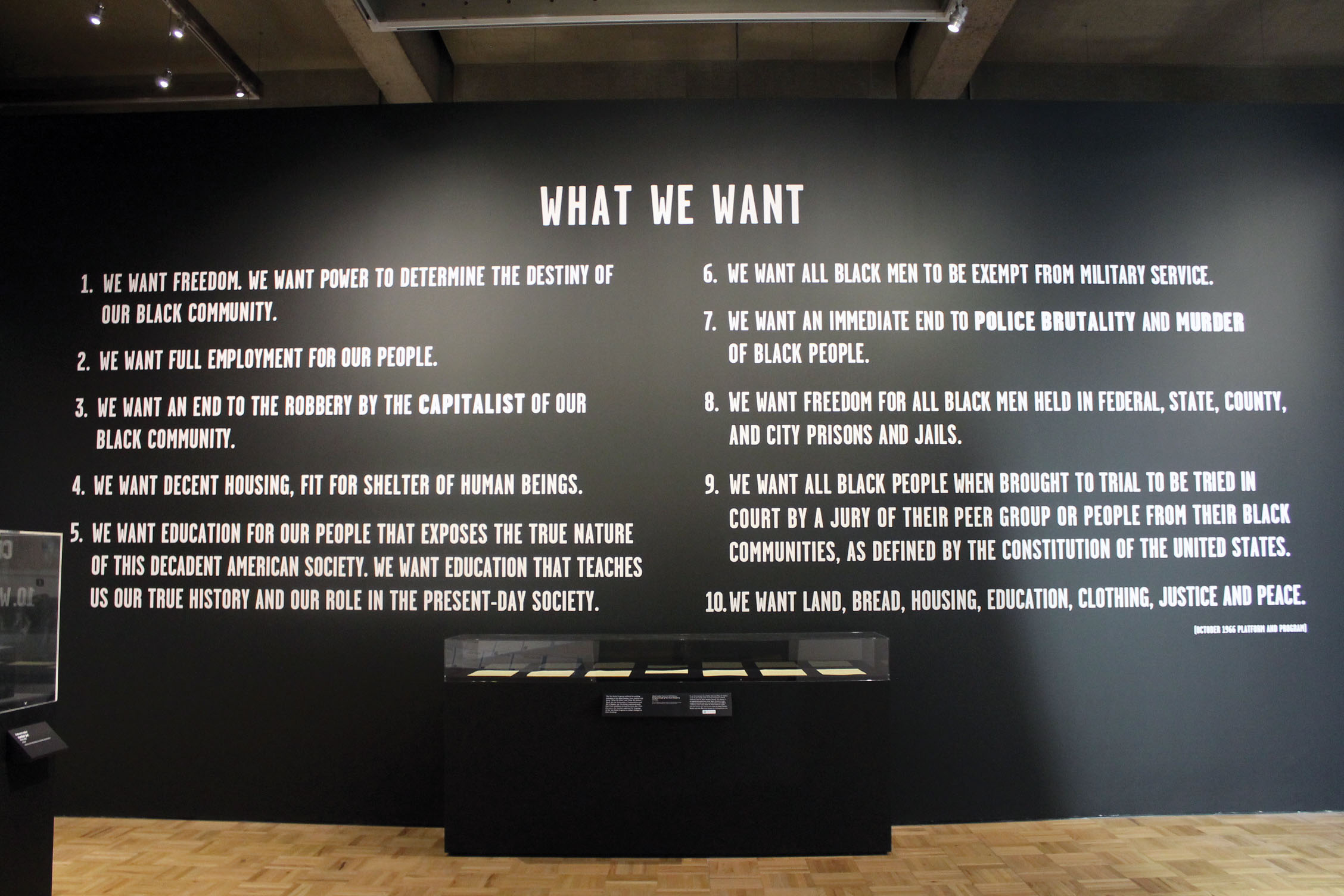

These words were written by Huey P. Newton who, with Bobby Seale, developed a ten-point program to help launch this revolution from their hometown of Oakland, California. The ten-point program was born out of frustration, as Newton and Seale had witnessed repeated acts of “police brutality and murder of Black People” with no end in sight.2 In 1966, after the city council’s refusal to audit police brutality in their neighborhood, Newton and Seale set out to determine the “destiny” of their own community. Calling themselves the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, they began to deliver a wide-range of services; most notably the Breakfast for Children Program, the Sickle–Cell Anemia Research Foundation, Community Learning Center, and the Intercommunal Youth Institute. Providing food, health care, and education was central to the identity of the Black Panthers, but as Newton stated, these community programs were only a salve to the issues revolution would resolve. This was particularly true with respect to the Panthers struggle to gain both political and economic power over the governing space of their neighborhood. Full seizure of both power and space required radical confrontation with “racist power structures”—the police department, legal systems, and local government. It required insurrection. Through street rallies, protests, and patrolling of the police, the Black Panthers gained visibility and a steady following. By 1970, the party grew to include over five thousand members with more than forty chapters formed across the United States.3

The Black Panthers also established a strong international presence in Asia and Africa by linking their domestic mission for black liberation with global movements opposing American imperialism.4 By 1972, the party’s following began to wane as their message and focus became fractured: between proponents of armed insurrection and those who believed community service and electoral politics would achieve their goals.5 Through a tumultuous period of interparty disputes, shootouts, and violent encounters with the FBI and local police, fifty subsequent years has witnessed the memory of the Black Panthers locked in an endless standoff between these two opposing narratives, both clouded by myth and misunderstanding. It’s in a pursuit to translate this tension found in the Panthers’ history that the Oakland Museum of California presents All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50.6

The Black Panther Party was formed out of left-wing values, mobilizing the rhetorical persuasion of Black Power, the armed insurrection of black nationalism, and the self-help ethos of black pride and determination. Early in their formulation for revolutionary socialism, Newton and Seale began drafting a mission statement that would eventually become their Ten-Point Party Platform and Program.7 The platform and program distilled the party’s beliefs into a portable and reproducible device, a type of map or what Bruno Latour refers to as an “immutable mobile.” For Latour, maps were ideal for obtaining knowledge because of their simultaneous immutability and mobility.8 In other words, in printed form, the medium specificity of the Black Panther Platform and Program allowed for a mobile yet unchangeable transference of a given knowledge set. Written on college-ruled paper, the drafts of the platform are presented in the second gallery of the exhibition—notes carefully displayed in Plexiglas vitrines. These “immutable mobiles” serve as reminders of how remarkably deft the Panthers were in rhetorical persuasion.9

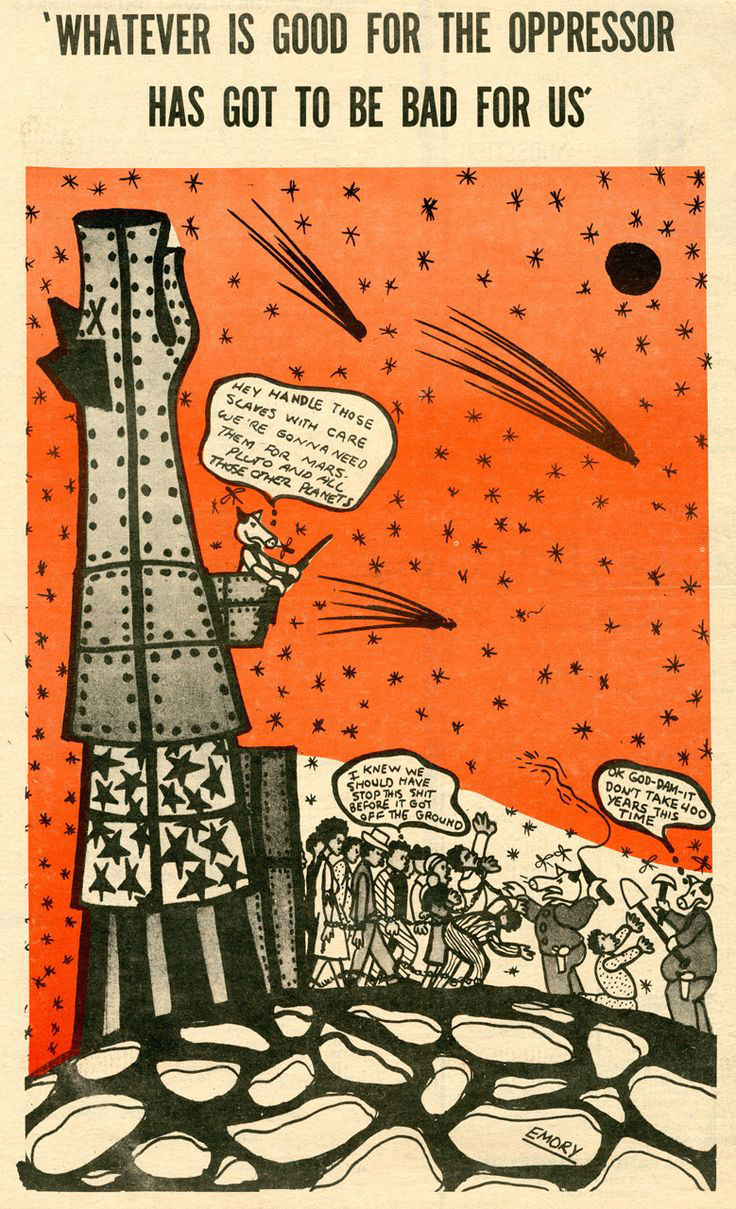

One only needs to recall the powerful designs of propaganda graphics to be reminded of the Panthers’ expertise in crafting a visual rhetoric of revolution. In the educational gallery, a wall displaying the cover art of early copies of Black Panther prominently line the wall. It is unclear how the curator arrived at choosing the over two dozen pamphlets displayed, but the visual dimension of the Panthers’ practice is clearly captured. Missing, however, were Emory Douglas’s propaganda posters urging for community control of the police. In a graphic series bearing the title “community control of police,” Douglas visually captured the Black Panthers’ conviction that the police were “rather low-lifed animals…pigs” that were occupying their neighborhoods. 10 Using symbolic language and imagery were effective tools to inform and educate the community and even recruit party members to help promote their ten-point program.

But is this what revolution looked like in the hands of the Panthers? Was producing a self-image of radical insurgency the Black Panthers’ most effective operational strategy?11 These questions are not addressed or even asked in the show. And while it’s clear that visual communication was an essential component in the Panthers’ operational strategies, the exhibit suggests that the Black Panthers’ support of the community through services and programs were in fact their most “innovative” tactics for revolution.

Displayed next to the title “revolution = innovation,” documentary photographs index the variety of Panther services that emphasized self-determination. The Panthers adopted the philosophy of self-determination early in their formulations of the ten-point platform and program, writing their desire to facilitate access to “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace.” However, self-determination in the hands of the Panthers was not concerned with assimilation. Unlike the self-help ethos of Marcus Garvey, who emphasized racial uplift and economic betterment, the Panthers proposed a different type of self-determination. While Garvey’s call for job training, education, or even child-development lessons on speech, physical education, grooming, and hygiene figured in many of the Panthers community programs, the Panthers privileged the exercise of self-determination as an important bridge or pathway to knowledge and self-awareness—the most potent Panther tool for revolution.12

In distinction to the era’s self-help politics, the Panthers adopted ideologies from Black Power and Black Nationalism to create an Oakland-specific approach to self-determination. The same year Newton and Seale were developing their Platform and Program, Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton were writing Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. The book defined Black Power as “full participation in the decision making process affecting the lives of black people and recognition of the virtues in themselves as black people.”13 Additionally, Carmichael and Hamilton’s form of Black Power emphasized the community control of institutions. It was within this definition that Panthers carried out their community programs.

In an essay titled “The Anti-Poverty Hoax: Development, Pacification, and the Making of Community in the Global 1960s,” Ananya Roy reveals a dark underbelly of community development and the self-help ethos of the 1960s. Roy highlights how the Ford Foundation’s Gray Areas Program and later federal programs such as President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty both sought to pacify urban violence with a soft programming of community development. She makes clear that it was precisely in this moment that the social problem of poverty was made visible for the first time as an urban problem, with community development programs tackling poverty as a spatial phenomenon. Of interest here is Roy’s reading of the Black Panther Party and their community programs as a spatial praxis. Building on the thesis of Robert Self’s spatial analysis of the Black Panthers, she describes the Panthers as “rupturing the self-help programs initiated by Gray Areas” by putting “forward a vision of self-determination.”14

In the exhibition, little is revealed about this history of the Black Panther Party and its relationship to the era’s urban politics. As part of the exhibition, the museum includes a self-guided walking tour of the Panther neighborhood in North Oakland. The museum’s guide to the neighborhood is administered by Detour.15 Site visits include Newton’s elementary school, Bobby Seale’s house, as well as a visit to Merritt College, where Newton learned of Malcolm X and the Black Muslim Program, the African liberation movement as well as of Mao Tse Tung and the People’s Revolution in China—all of which informed the Black Panthers’ fight for liberation both at local and global scales.

While the tour fills some of the gaps in the Black Panthers’ Oakland-specific history, the pilgrimage to the Panther neighborhood only begins to suggest the Panthers’ fraught relationship to the city, with no substantial reference to the region’s complex urban history. For this history, you’ll have to rely on Robert Self’s American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland, published in 2006.16 The book is conspicuously missing from the museum’s stack of recommended books on the Panther Party, even though it provides one of the most thorough arguments of the Black Panther Party as a place-specific movement. Self examines the spatial dimensions of African-American ideologies and effortlessly stiches together a narrative of power struggle that situates the Black Panther Party at the center of race relations and their spatial processes in Oakland. In particular, Self locates Oakland as the center of anti-poverty programs and consistently links both the oppression and opportunities of the Oakland Black community to urban policies that informed the development and redevelopment of city. Self examines Oakland’s urban politics between 1965 and 1977—highlighting the Panthers’ effort to build their own utopia, or what they referred to as the “people’s city.”17

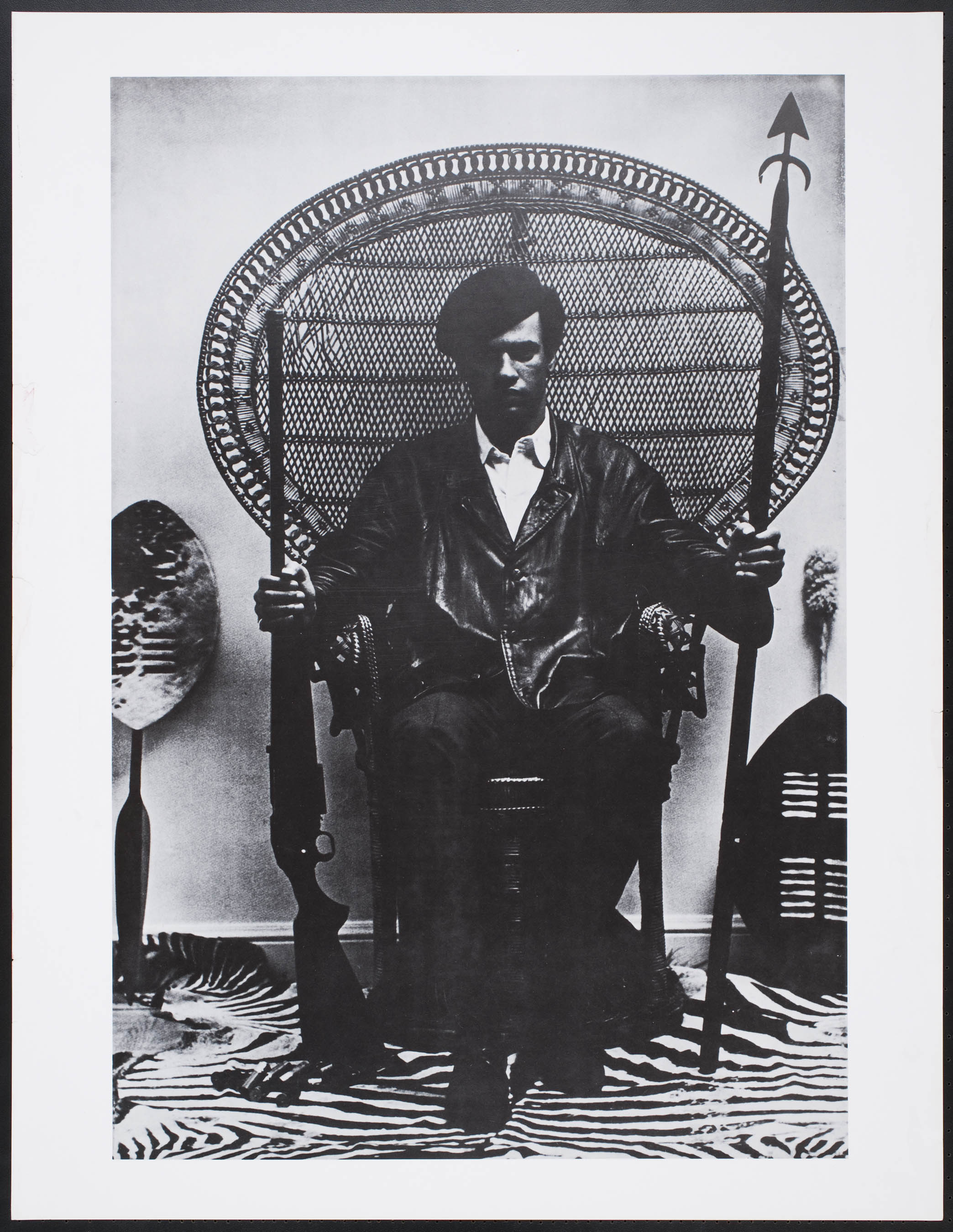

Revolution is the one thing that Self seldom mentions—what it looked like, how it was deployed, and why it was so important to the Panthers’ identity. This, perhaps, is where the exhibition puts forward its most compelling presentation of the Black Panther Party. While the examination of the party’s relationship to the idea of revolution is latent in the exhibition, the show submits a series of speculations of what an act of revolution would look like today. Upon entering the main gallery, visitors encounter a bronze wicker chair titled, Proposal for a Monument to Huey Newton at the Alameda County Courthouse, Oakland, CA (2004), by artist Sam Durant.

Durant’s sculpture is a replica of the fan-back chair Newton sits on in the iconic image of him authoritatively posed with a shotgun in one hand and a spear in the other. As with all effective sculptural monuments, Durant’s monument is site-specific and asks the viewer to remember the infamous Black Panther trials that took place in the courthouse just steps away from the museum. The chair is also an invitation; it asks visitors to sit and embody the attitudes of the Panthers and perhaps even reconstruct the Panthers’ revolutionary values for our contemporary condition.

Artist Hank Willis Thomas also provides an interactive piece. In Two Little Prisoners (2014), Thomas captures the revolutionary spirit in pint-size rioters. Made from magazine clippings of the 1964 Watts Riot, the photo collage, enlarged to a human scale and placed on a mirror, beckons the viewer to reflect on herself in relation to the two young boys and police officer hovering in the picture frame. These subtle invitations make “Power to the People” one of the museum’s most interactive and experiential historical shows. It also powerfully captures narratives of the lives of artists, musicians, and poets influenced by the Black Panthers. This intention is clear in a photo essay of portraits taken from the book The Black Panthers: Portraits from an Unfinished Revolution, or in a short video series, where writer and poet Chinaka Hodge delivers the most arresting poem on civil rights, Black Power, and the Black Panthers’ collective fight for freedom.

While black political struggle extends far beyond the singularity of the Black Panther Party, as we stand poised to enter an uncertain future, a celebration of the Panthers’ fiftieth anniversary is an appropriate time to remind us that equality is never given freely. The Black Panthers’ five simple words “all power to the people” is perhaps the most significant vehicle for self-determination and preservation we can call on today.

-

Huey P. Newton, To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton (New York: Random House, 1972), 104. ↩

-

“Interview with Bobby Seale,” personal interview, Washington University, November 4, 1988. Interview gathered as part of Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads 1965–1985, episode 203–28. ↩

-

Wall text, All Power to the People, Oakland Museum of California, October 8, 2016 to February 26, 2017. ↩

-

Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 3. The authors cite “the Functional Definition of Politics” as Newton’s seminal essay, where Newton wrote: “great similarity between the occupying army in Southeast Asia and the occupation of our communities by racist police.” ↩

-

Wall text, All Power to the People. ↩

-

The show’s introductory wall text begins with the statement: “When Bobby met Huey, the world was on fire” and goes on to describe how the Black Panther Party stood “at the forefront of revolutionary change…[and whose] full history is often misunderstood. Many still fear the Panthers and are unaware of their basic nature and intent.” ↩

-

Robert Self, “‘To Plan Our Liberation’: Black Power and the Politics of Place in Oakland, California, 1965–1977,” Journal of Urban History, vol. 26, no. 6 (September 2000): 759–792. ↩

-

Bruno Latour, “Visualization and Cognition: Drawing Things Together,” in Knowledge and Society Calling Studies in the Sociology of Culture and Present, ed. Henrika Kuklick, vol. 6 (Greenwich, CT: Jai Press, 1986). Latour defined post-enlightenment maps as “flat inscriptions” that enabled the accurate transference of knowledge from one medium to another. Describing the story of French explorer La Perouse, whose sole mission was to bring back a better map of Sakhalin, Latour focuses on two key factors that, to his mind, make the map a medium for obtaining knowledge: immutability and mobility. In other words, the maps medium specificity allows for a mobile yet unchangeable transference of a given knowledge set. ↩

-

The Party Platform was printed in every issue of the magazine Black Panther. ↩

-

Louis Massiah, “Interview with Huey P. Newton,” personal interview, Washington University, May 23, 1989. Interview gathered as part of Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads 1965–1985, episode 203–24. ↩

-

Nikhil P. Singh, Black Is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 83. Singh describes the Panthers as vanguard “practitioners of an insurgent form of visibility.” ↩

-

David Hilliard, The Black Panther Party: Service to the People Programs (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008), 56–60. ↩

-

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, (New York: Random House, 1967), 47. ↩

-

Ananya Roy, Stuart Schrader, and Emma S. Crane, “The Anti-Poverty Hoax: Development, Pacification, and the Making of Community in the Global 1960s,” Cities, vol. 44, no. 1 (April 2015): 139–145. ↩

-

Detour is a contemporary version of the fictitious Baede-Kar guide system that Reyner Banham invented in his tour of Los Angeles (Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, 1972). ↩

-

Robert Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). ↩

-

Robert Self, “To Plan Our Liberation,” 770. ↩

Rebecca Choi is a PhD candidate in architectural history at the University of California. Her scholarship focuses on the history of late twentieth-century architecture and urbanism, with an emphasis on Los Angeles.