As the dust of demolition settles on 53rd Street and all that remains of the Folk Art Museum's former home are the iconic bronze panels—whisked away into storage, fragments to be conserved and perhaps displayed in some future MoMA exhibition on lost early twenty-first-century architecture—it seems a fitting moment to reexamine the shrill and sadly stunted public debate that preceded the arrival of the wrecking ball. In its form it resembled countless other New York City preservation debates, one part blood sport, one part farce, each side convinced that giving any quarter to the opposition was the surest way of losing everything. But what was really lost was any meaningful discussion of how cities determine what parts of their history have value; what the role of architecture might be in remaking structures that no longer serve their original purpose; and what, in environmental terms, should set the limits between willfulness and waste.

Nearly all of MoMA’s arguments for demolishing its diminutive neighbor betrayed a failure of imagination that bordered on bad faith. Praising the integrity of the Folk Art’s design precisely to condemn it, MoMA systematically rejected the possibility that the building might play any productive part in its expansion plans.1 With the backhanded compliment characterizing the Folk Art building as a “bespoke suit,” there was a clear suggestion that its elegant fabric and fit were incompatible with any other program; to alter the suit would have been to ruin it completely.2 Of course, this conveniently ignored the fact that MoMA’s own original bespoke suit, by the renowned tailors Goodwin and Stone (and hailed at its opening in 1939 as the world’s first purpose-built building for the display of modern art), had been nipped, tucked, resized, repurposed, and resurfaced on six different occasions over the last seventy-five years.

MoMA’s arguments were ultimately seconded by its latest architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, who, in a subtle shift of metaphor, publicly cited the “obdurate” qualities of the Folk Art’s design as a reason for its demise.3 This strategy of “blaming the victim” was particularly surprising coming from designers who had elsewhere been so inventive in adapting complex, difficult urban fragments to new uses: From Lincoln Center to the High Line, DS+R has become the go-to firm for transforming sows’ ears into silk purses.

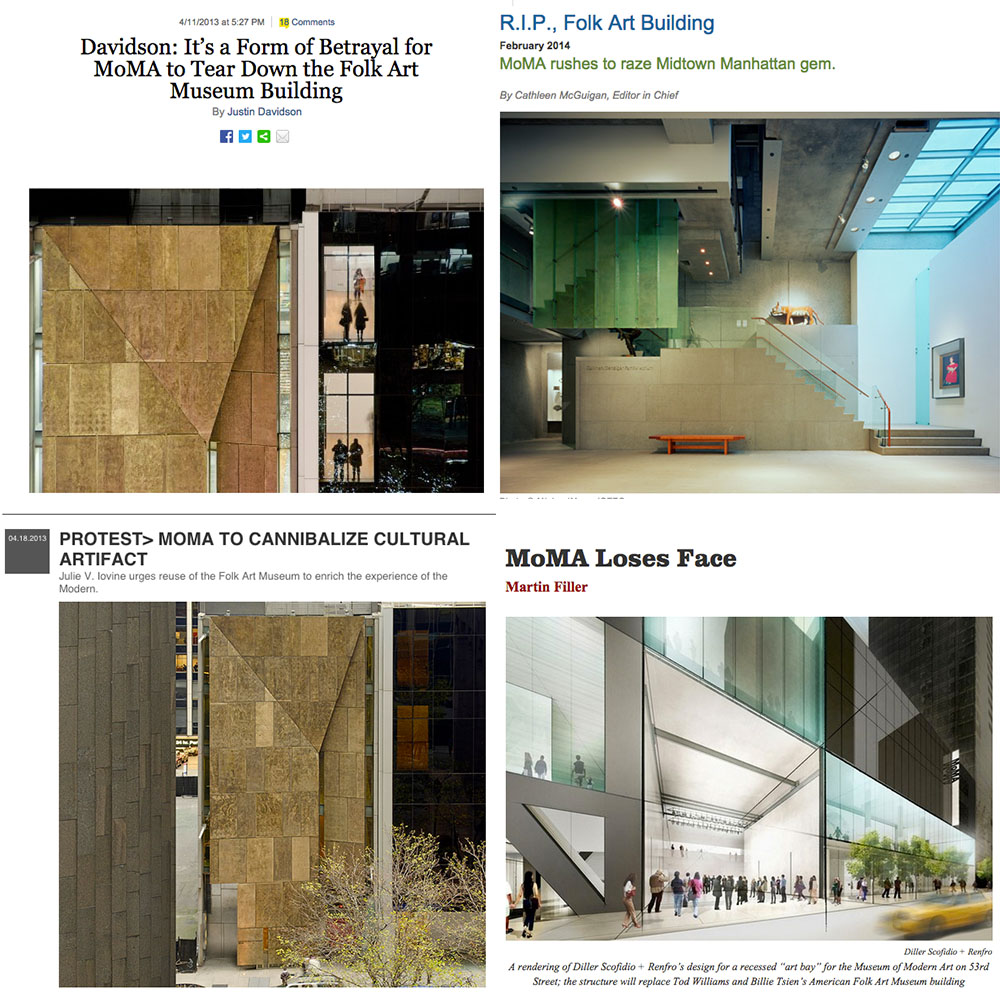

But the Folk Art’s defenders did their cause little good with exaggerated claims of their own, and while no doubt well-intentioned, at times the hyperbole loaded on the poor little building seemed enough to crush it without any help from MoMA. Folk Art was heralded as “an architectural gem,” “a beautiful and inventive jewel,” and “an acknowledged masterwork” among dozens of other encomiums.4 This deafening insistence on the exceptional architectural quality of the Folk Art building seemed to deliberately ignore what an awkward space it had always been for presenting art and how poorly it had served its visitors.5 Nevertheless, the consensus claim among the Folk Art’s supporters was that the building deserved to be kept, in its entirety, exclusively because of its great architectural merit.

The implicit principle, that only buildings of architectural merit should be preserved, was a profoundly anti-urban argument that misunderstood the very structure and significance of the city, a riotous collection of mostly indifferent individual buildings that together, miraculously, form an ensemble of great quality and meaning. Worse still, this “masterpiece” argument insisted on peerless artistic value as the threshold for public concern about the built environment, an impossibly high standard that ultimately debases our sense of what architectural value is. Hoisted by the petard of such preservationist rhetoric, any old thing we want to save must be a masterpiece precisely because we want to save it. In the end, this instrumentalized logic undermines the very standard of quality it professes to uphold.

And then there was a third voice in the debate, audible mostly in its silence, wondering what all the fuss was about. After all, here was a private owner making complex decisions about the best use of private property; what was the public dimension of such a discussion? And in many ways, the implications of this unvoiced question were the most important of all: What should be the public obligations of private institutions as they plan their growth from one generation to the next? Does the public good play any role and if so, how should it be defined? And by what mechanisms does the public protect the built heritage of the city, which is its urbanity as much as its history?

One source of confusion came from an insistence on considering buildings as works of art and curiously, both MoMA and its critics advanced the same flawed notion that buildings have a kind of timeless consistency and balance that suffers irrevocably if any part of the whole is altered. Yet no building remains the same over time: the adaptation of interiors to changing demands in use; the slow degradation of materials, their renewal and replacement; the gradual evolution of the surrounding urban context, all of these normal events over a building’s life slowly erode any notion of immutable artistic integrity.

And so, we had the wrong kind of discussion about the Folk Art’s future—either/or, kept or demolished—whereas the discussion we needed to have would have acknowledged a much wider range of positions, more or less, limited change to extensive replacement. Such a discussion might have introduced some nuance in acknowledging that the exterior of any building shapes public space and that public space has a different and more widely shared importance than private use. Thus, considered as an urban artifact, we might have agreed that not all parts of the Folk Art building had the same significance: massing, exterior form, and especially façade arguably mattered more than interior volumes and past programs.

We might also have acknowledged that the Folk Art was a mixed achievement: an ambitious, quirky project with some beautifully crafted spatial moments as well as some dark, cramped and clumsy ones; a highly idiosyncratic building, which briefly fulfilled its original program and then became a kind of lavish ruin. Yet none of this would have diminished its claim to conservation and intelligent reuse. On the contrary, the reason we should have considered saving some part of the Folk Art was precisely because it didn’t rise to the level of an undisputed masterwork; the real question was how much of it could be kept and to what purposes it might have been put. And, arguably, those purposes should have reflected a host of considerations beyond MoMA’s expansion plans—the character of 53rd Street, the increasing homogeneity of Midtown, the value of collective memory—and how to establish a hierarchy between these competing claims. But such questions couldn’t be intelligently asked until the idea of Folk Art as an untouchable masterpiece was abandoned.

MoMA’s architects glibly dismissed as “façadism” the possibility of keeping some part of the Folk Art’s exterior while substantially changing the spaces inside, an intellectually shallow response that ignored the reality of how urban spaces change over time.6 New York abounds in buildings where exterior form persists even as internal use is transformed beyond recognition: from the manufacturing lofts of SoHo, remade first as artist’s studios and then as luxury condos, to school buildings reinvented as museums and correctional facilities. And then there are the countless examples in European cities, which, with much more history to spare, are consistently more careful about editing urban detritus with a view to reuse: Think of Scarpa’s showroom for Olivetti inserted behind the sixteenth-century arcade of Piazza San Marco in Venice, or the same architect’s sequence of modern galleries fashioned in the ruins of Verona’s Castelvecchio, to take only the most obvious examples. Or consider the transformation of Paris over the last thirty years, where a train station, a slaughterhouse, a government ministry and a seventeenth hôtel de ville were all successfully transformed into museums. Were we really expected to believe that MoMA was incapable of turning a museum into…a museum?

But beyond this purely architectural logic, the most compelling consideration in the discussion we didn’t have is ecological. We can no longer justify (if we ever could) the wholesale destruction of a twelve-year-old building that would cost well over a thousand dollars a square foot today.7 And though MoMA’s board has pockets deep enough to write off even this kind of extravagance, if one considers the Folk Art building in terms of the material and human ecology of the city, the calculations change. Think of the Folk Art as entrained energy and mass; as hundreds of thousands of Btu’s spent fabricating its materials; as tens of thousands of designer-hours of creative effort and worker-days of careful construction; and as thousands of cubic yards of unrecycled landfill. Consider it, in short, in terms of the fullness of its environmental history, as embedded social investment, to be reaffirmed or squandered: Seen in this light, the façadism argument for demolition collapses under its own weight.

Finally, perhaps the flaw in the arguments on both sides came not so much from thinking of buildings as works of art but as the wrong kind of art. In place of sculptural masterpieces, Cubist collage, Dada ready-mades, Surrealist exquisite corpses and Mertzbau would all seem to be better models, as they start with the premise that materials and forms that have already been given meaning in the past may have still other, unknowable meanings in the future. This represents not just an ecology of materials but of signification, the understanding that regardless of what we intend, history recycles meanings in much the same way it does landscapes, built or natural.

Such an approach to urban history extends not simply to materials and forms but to ideas, to finding a way of preserving and engaging meaning in a constantly evolving ecosystem of larger and smaller fragments. Sometimes this will lead to imagining new uses for intact old buildings; sometimes to altering old buildings to fit changed programs; and occasionally, to wholesale demolition and replacement. But most of the time, if we take our cities seriously, it will mean fashioning a shifting continuity among the pieces that chance has left us, a renewed equilibrium that answers to urban and urbane values, which is to say, public ones.

-

See, for example, Glenn Lowry’s remarks at the Architectural League’s “A Conversation on the Museum of Modern Art’s Plan for Expansion,” January 28, 2014. ↩

-

Barry Bergdoll in an interview with New York Times reporter Robin Pogrebin (April 22, 2013) was the first to use the term bespoke in reference to Folk Art; it was subsequently picked up by Liz Diller in several public presentations of DS+R’s new plans to replace the building. ↩

-

Liz Diller, in her prepared remarks at the Architectural League’s “A Conversation on the Museum of Modern Art’s Plan for Expansion,” January 28, 2014. ↩

-

“Gem”: Justin Davidson, Julie Iovine, and Martin Filler; “jewel”: Cathleen McGuigan; “masterwork”: Jospeh Giovannini and Julie Iovine. ↩

-

Jerry Saltz was virtually the only critic to temper the debate with an evaluation of Folk Art’s shortcomings as a space of display; see his early articles on the proposal to demolish AFAM in New York magazine and several postings on the magazine’s blog Vulture. ↩

-

Liz Diller used this term to characterize the design of Folk Art in her response to questions at the Architectural League’s “A Conversation on the Museum of Modern Art’s Plan for Expansion.” ↩

-

The published cost of the original AFAM project in 2001 was $32 million for 40,000 square feet of space. See, for example, “American Folk Art Museum Puts Down Healthier Roots,” New York Times, (April 2, 2013), nytimes.com/2013/04/03/arts/design/american-folk-art-museum-puts-down-healthier-roots.html. ↩

Stephen Rustow is a principal of Museoplan and a Professor of Architecture at Cooper Union.