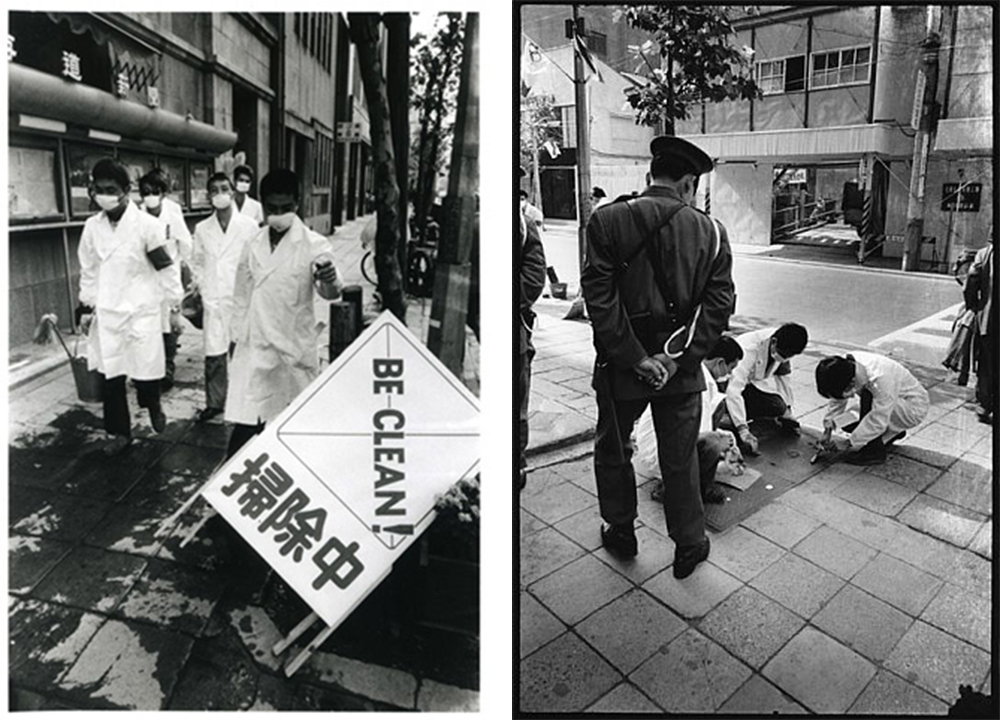

On October 16, 1964, the artist collective Hi Red Center, clad in sanitation masks and white uniforms and wielding small brooms and toothbrushes, spent several hours meticulously cleaning the streets of the Tokyo district of Ginza, amid the hustle and bustle of a “normal” day.1 Titled “Movement to Promote the Cleanup of the Metropolitan Area (Be Clean!),” the event was an absurdist happening staged during the internationally telecast 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games that satirized the behaviors then promoted by the Japanese state as part of its push for a “face-lift” for Tokyo’s streets and surfaces.2

The state’s cleanliness campaigns, marketed as a “Beautification of the Capital Movement,” and financed with some 4.7 percent of Olympic investment funding by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government—more than that spent on Olympic installations—were designed to present the city and its bodies in a way that would satisfy the expectations of the Western gaze.3 Hi Red Center’s media-conscious performance, heralded as exceptionally rigorous civic service by several police patrols, subversively expressed the social tension latent within Japan’s postwar reconstruction and Allied Occupation. Staged in front of the Hokkaido newspaper company, near Kenzo Tange’s National Olympic Stadium in one of the busiest commercial districts of Tokyo, Hi Red Center’s actions amplified and distorted the activities and objects that were central to the state’s campaign.

To add further deceit to their demonstration, the collective distributed a series of flyers produced by a fictional company listing the names of twenty-one entities—real and otherwise, such as the Metropolitan Environment Execution Committee and the Housewives Federation—that were allegedly sponsoring the efforts of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.4 Journalist Minoru Hirata, who had been photographing the works of the collective’s Dada-inspired contemporaries such as Zero Jigen, also stood by to document the spectacle. Hi Red Center put dirt and debris at odds with the state’s very notion of “modernity.”5

As a globally circulated media opportunity, the 1964 Tokyo Olympics formally facilitated a timely re-scripting of postwar Japanese society’s increasingly consumer-oriented identity, based on the influential American model. Hosting the highly politicized event allowed the state to justify the caustic redevelopment projects deemed necessary for a modern Japanese society. Between 1959 and 1964, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government planned and financed the erection of 10,000 office and residential buildings, 100 kilometers of highway, 40 kilometers of additional subway lines, an exclusive rail that moved between Haneda International Airport to Tokyo’s commercial core,6 four five-star hotels, and the introduction of a Shinkansen (“bullet train”) that would move between Tokyo and Osaka.7 Hosting the Games also functioned as an opportunity for the state to reconstruct a highly manufactured, exportable Japanese mass culture for domestic and international consumption, in the context of a youth-oriented global market being reconfigured around leisure.8 Amid Japan’s postwar economic reconstruction, early forms of electronic mass communication such as television and radio—widely disseminated within the Japanese domestic sphere—were increasingly essential for this cultural re-scripting. Within two decades, Tokyo, 51 percent of which had been destroyed by the war’s end, had a population whose majority owned a television and regularly followed the plots of American serials.9 Time magazine called Tokyo of the early sixties the “most dynamic city on the face of the earth,” with a pace of life “double that of “New York.”10

In 1964, the importance of being physically present at the fairly inaccessible Games was suddenly contested. The patriotism and allure of physical human prowess along with the fantastical “exotic” environments supporting it (luxurious Japanese hotels, parades, theme parks, nightclubs, promiscuous call-girl imagery, and polished historical tourism) could now be transmitted electronically as reality television before “reality television.” A fundamental function of the Tokyo Olympic Games, then, was not only to internally reinforce a new image of Japanese economic prosperity and the diversity of consumer-oriented lifestyles this prosperity enabled but also to disseminate these images internationally. Included in this portrayal of Japan’s new sociocultural identity, while to some degree satisfying the protocol encouraged by the state’s aggressive campaigns, Hi Red Center’s staged scrubbing criticizes Japan’s callous preoccupation with cleanliness at the expense of all else.

As it has waged its own cleanliness campaigns to satisfy the criteria of the International Olympic Committee, the preoccupations of the Brazilian state in 2016 have not been too different. Despite weathering an alleged coup d’état following the fallout of the 2014 statewide “Car Wash” corruption investigation, the state still occupied itself with preparations for the predictable influx in international tourism and capital promised by the Games. Manifest most notably in the city of Rio de Janeiro’s eviction of some 77,000 favela residents—with minimal financial compensation obligated by Rio’s city council—the public/private development boom has required no consent from the displaced.11 The Brazilian state also built several kilometers of sculptural concrete wall lining the João Goulart Expressway to obscure any sight of favelas for those who travel between Rio’s Galeão International Airport, through Maré, into the city’s core and promised to intensify “mosquito control” and ensure access to condoms and insect repellent for all athletes and visitors concerned about Zika virus.12

On August 5, 2016, following interim President Michel Temer’s initiation of the Summer Games, protesters (some clad in T-shirts calling for Temer’s impeachment) entered the Olympic Park. Like many others who have recently criticized the state, these demonstrators were met by the rubber bullets and teargas of an increasingly present and well-funded Brazilian police and were forced from the sites of the Games. Alexandre de Moraes, Brazil’s justice minister, responded, “Freedom of speech is enshrined in the constitution, but these kinds of political protests cannot disturb the games.”13

In their effort to sanitize the civic realm and prevent demonstrations that distort images of a Brazil suitable for tourists and television, the growing number of crackdowns by Rio de Janeiro’s police were predominantly enabled by the CICC and COR, advanced intelligence systems that cover a sizable portion of the city.14 Inaugurated in 2005 as a state instrument to better monitor “daily demands” unfolding within civic space as well as “the great events the city [of Rio] will host,” the CICC (Integrated Command and Control Center) involves a variety of state agencies in multiple levels of government.15 Rio’s panopticon–cum–Blade Runner CICC, one of many used in Brazil’s twenty-six federative units, is in turn surveyed and managed by a centralized CICC within the capital of Brasília. The central element of Rio’s CICC is a 9-by-17-meter screen, containing ninety-eight LED displays that can stream, in real time, the feeds of about 3,200 mobile and stationary surveillance cameras.16 The COR (Centro de Operações Preifetura do Rio de Janeiro), a second, city-run intelligence system inaugurated by the Rio police force in 2010 in anticipation of the 2014 FIFA World Cup, streams footage and gathers data from 560 cameras positioned within the municipality’s thirty departments into a different, but equally insular, control room.17

In the televised broadcasts of the Tokyo of the 1964 Games, products of the “Beautification of the Capital Movement,” waged to suppress that which did not fit the aesthetic of a developed, postwar nation, are all but invisible. The products of Brazil’s campaigns, as grand development projects, publicly distributed condoms and mosquito repellent, and costly security apparatuses that mediate unruly demonstration in almost real time, are all but invisible as well. Regardless of these efforts’ efficacy in reinforcing the Brazilian state’s preferred imagery, under the slightest pressure they also unravel into self-critique amid Rio’s blatant social inequity, proving no more effective at sincerely addressing “cleanliness” and “modernity” than Hi Red Center’s toothbrushes scrubbing debris in the Ginza of half a century prior.

-

Hi Red Center was founded in 1963 by Genpei Akasegawa, Natsuyuki Nakanishi, and Jiro Takamatsu following their 1962 guerrilla performance on the Yamanote Line in Tokyo, which entailed the collective’s casual carrying of junk onto the train while wearing salaryman suits and white face paint. See Doryun Chong, Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 27. ↩

-

Alexandra Munroe, Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1994), 179. This was the first Olympic Games observable “worldwide” via international telecasting. See Marilyn Ivy, “Formations of Mass Culture,” in Postwar Japan as History, ed. Andrew Gordon (Berkeley: University of California, 1993), 248–249. ↩

-

Yoshikuni Igarashi, Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945–1970 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 143–163. ↩

-

Jilly Traganou, “Institutional Appropriation: Impersonating,” in Designing the Olympics: Representation, Participation, Contestation (London: Routledge, 2016), 265. ↩

-

Michio Hayashi, “Tracing the Graphic in Postwar Japanese Art,” in Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde, 102–103. ↩

-

After the war and during the Allied Occupation, and as a direct result of Emperor Hirohito denouncing his divinity (via radio) and the installment of a parliamentary democracy, many Japanese considered the center of Tokyo to be spiritually, and politically, empty. Roland Barthes eventually further popularized this idea in his 1970 text The Empire of Signs. ↩

-

Robert Whiting, “Olympic Construction Transformed Tokyo,” Japan Times, October 10, 2014. ↩

-

Le Mystère Koumiko, directed by Chris Marker (1965; Sofacima-Apec-Joudioux Films). ↩

-

Ivy, “Formations of Mass Culture,” 248–249. ↩

-

Time’s description of Tokyo is cited in Whiting, “Olympic Construction Transformed Tokyo.” ↩

-

James Armour Young, “The Rio Olympics Is Being Used as ‘an Excuse’ to Evict Poor People from Valuable Land,” VICE News RSS, December 13, 2015, link. ↩

-

Donald G. McNeil Jr. and Sabrina Tavernise, “W.H.O. Says Olympics Should Go Ahead in Brazil despite Zika Virus,” New York Times, June 14, 2016, link. ↩

-

Lulu Garcia-Navarro, “Controversy Grows in Rio over Political Protests during Olympics,” NPR, August 9, 2016, link. ↩

-

Control Syntax Rio: Monitoring the Collective Body, installation at Het Nieuwe Instituut (June 2016), link. ↩

-

These agencies include the Military Police, Civil Police, Fire Department, Mobile Emergency Service (SAMU), Federal Police, Federal Highway Police, and Municipal Guard. See Fabiana Paiva, “Imprensa RJ,” Subsecretaria de Comunicação Social, Governo do Rio de Janeiro, May 31, 2013, link. ↩

-

Paiva, “Imprensa RJ.” ↩

-

Dia Kayyali, “The Olympics Are Turning Rio into a Military State,” Motherboard, Vice, June 13, 2016, link. ↩

Cameron Cortez is a recent graduate of the GSAPP and is currently looking at doors, and happenings behind them, in Beijing.