To get to Foremost, Alberta, take the 4 through Sweet Grass and Milk River, then hang a left on 61 and shoot east toward Medicine Hat. Drive a couple hours down gravel roads across the berms and bowls of glaciated grasslands, past alfalfa and barley fields, where cell phone service dips out and the radio turns to fuzz.1 Directions to Foremost, though, are rarely asked for.2 It’s a village of about five hundred, whose residents are mostly farmers—a modest town with a solid high school hockey team settled by Estonians homesteaders in the early twentieth century. Though remote it may be, Foremost is located in a strategic sector of the middle of nowhere. If not a stone’s throw, then it’s perhaps a stone’s catapult from the US–Canada border, only 40 or so miles north. Above the village lies over 700 nautical miles of class G uncontrolled airspace that stretch to 1,000 feet above sea level, at which point CYR restricted airspace begins—meaning aircraft that fly above 1,000 feet can’t enter the area, but those flying below are permitted without the oversight of air traffic control. In addition, these skies are unusually clear. In this part of southern Alberta, Visual Flight Rule compliance is enabled around 90 percent of the year. Visual Flight Rules depend upon Visual Meteorological Conditions set out by the Canadian Government, which dictate that in uncontrolled airspace daylight visibility be 1 mile and that aircraft must be 2,000 feet horizontally from any cloud and 500 feet vertically; Southeast Alberta’s prairies host the country’s sunniest skies.3 Foremost, it turns out, is the foremost place to test commercial drones in North America—or so the Canadian Centre for Unmanned Vehicle Systems (CCUVS) would like you to believe.4

Foremost is home to the CCUVS’s Foremost Centre for Unmanned Systems (FCUS), a Medicine Hat–based outfit whose primary terrestrial feature is a rentable Aerodrome. From this Aerodrome one can access the other portion of the Centre’s property—nearly 1,300 nautical miles of the restricted airspace above Foremost, secured by the CCUVS in cooperation with the Village of Foremost and Transport Canada, the arm of the Canadian government that controls transportation policies and programs. In 2014, Transport Canada approved the CCUVS administered airspace for Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) flying of unmanned vehicles, making the Centre the first training complex in Canada with such capabilities.5 (Within the United States, BVLOS flying can only be approved by special permit, and there are currently no US training centers for this type of unmanned vehicle flight.)6 This unique position poises the FCUS, as articulated in its business plan, to greatly benefit from the capital energies now injected into large-scale commercial drone use. The plan, the many training sessions offered at the CCUVS’s Medicine Hat location, and the website made by the Albertan government in partnership with the Village of Foremost all indicate that this is a town transformed—now a center of the nascent drone industry where new technology and it’s military-corporate application have been mobilized to drive development in a remote rural region. This, however, is not the case.

The ever-sunny skies above Foremost are still crop duster territory. And the Cedar Villa motel—the town’s one accommodation—hosts just a few guests, here on business to sell new threshers and repair the local grain elevator. A Chinese restaurant opens for dinners on weekdays; the town bar, too, shutters on weekends. Foremost is still pretty poor and pretty empty. So why this discrepancy between vision and reality? Why aren’t companies like Lockheed Martin (which CCUVS claims to be courting) or TransCanada (which operates an extensive network of oil pipelines in the area) flocking to the Aerodrome? Reviewing Foremost UAS Range Business Plan can elucidate why rural development at the hands of technological advancement and private-public partnership is difficult, and what the desire for it reveals about infrastructural systems and nation-state borders.

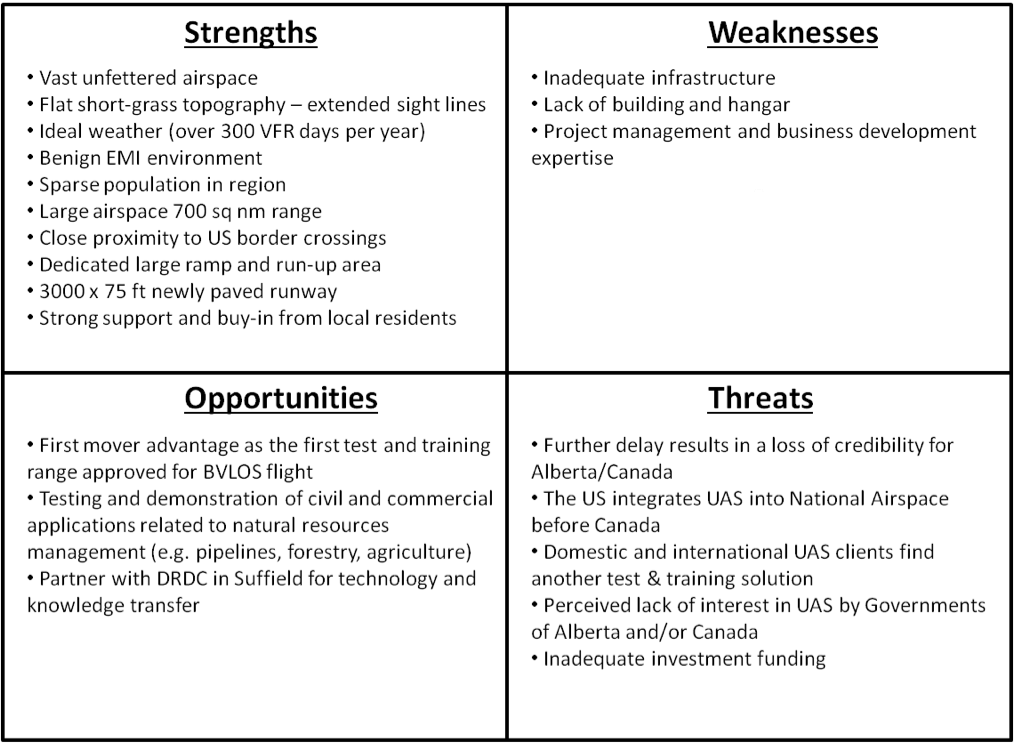

The Foremost UAS Range Business Plan can be found as a Microsoft Word file (titled “Foremost UAS Range Business Plan 3 FINAL.doc”) hosted on the Alberta provincial government’s website. It’s a sprawling document, covering a short history of unmanned aircraft, a description of Foremost, the origins of CCUVS, SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis, an articulation of the Centre’s goals, and a business model. The Foremost model hinges on ancillary services. National airspace has not yet been privatized, but access to it has (hence public-private partnership). The airstrip, its facilities, and the drone launcher are to be rented out to private companies. As the plan states:

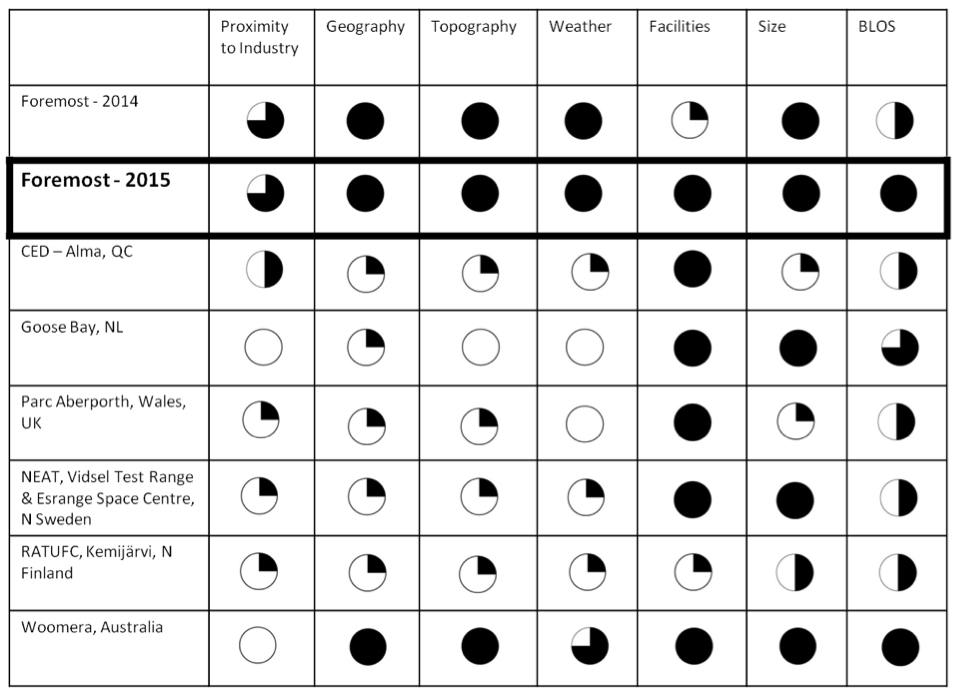

The primary revenue driver will be payments from companies that wish to lease the aerodrome and related infrastructure (and, thereby, use of the related airspace) for their UAS testing, training, research, and development activities. For companies engaged in testing civil and commercial applications, there are few non-military substitutes to the Foremost, Alberta UAS range. Indeed, there are currently no substitutes in North America that offer Foremost’s critical attributes of size, weather, and topography.7

Thus, through one small, aging piece of infrastructure, CCUVS is capitalizing less tangible assets: weather patterns, topography, geography, and policy. If not a new strain of twenty-first-century infrastructure, the Foremost Droneodrome at least indicates an infrastructural mutation. Creating systems more ethereal but less durable than the highways, railroads, and communication wires seeks to take advantage of, it is as equally constituted in the language of government regulations and corporate strategies as it is in physical structures. This is not an enacted infrastructure, writ in specific policies, but rather an enframed one, rendered through the logic of public-private partnership.

The Canadian Centre for Unmanned Vehicle Systems is a private, for-profit company founded in 2007. Spurred, perhaps, by decisions like Amazon’s to test drone capabilities in rural southern British Columbia (within walking distance of the US–Canada border), in 2014 the company recognized Foremost as an advantageous site and proposed reclassifying its existing airstrip (designed for small crop duster planes) to launch micro, mini, and MALE (Medium Altitude Long Endurance) drones. MALE drones include aircraft such as the General Atomics Predator Drone, used primarily by the US military.8 Without a plan for courting the companies it hopes to bring to its Aerodrome, nor any specifics about which sector of the industry it will cater its services to, CCUVS falls into a strange category of public-private partnership that looks to infrastructure and the logics of free trade to grow a local economy but that always ends up being more aspirational than actual.

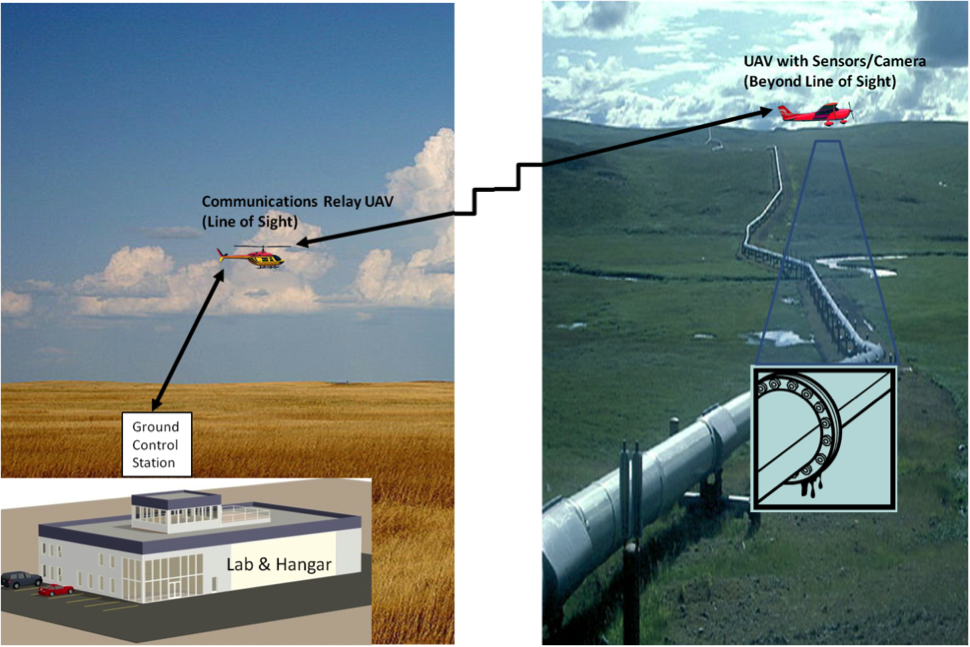

Hybridizing immaterial and physical infrastructures, the Foremost UAS Range identifies—indeed pitches—infrastructure as a multi-modal system engineered to generate a market. Mapped across a range of industries, the plan makes visible the relations between them all. “Civil and commercial” applications of UAS include such uses as “pipeline inspection” and “a variety of surveillance activities such as border surveillance.”9 Clearly the CCUVS sees the usefulness of its services for Alberta’s industries—one of which is oil and natural gas piped down from the Althabasca Oil Sands in the northern part of the province, and another of which is defense electronics. It also requires no huge stretch of the imagination to see the Canadian military taking advantage of the facility and its proximal location to the border, especially because the US government is already using MALE drones for surveillance along its perimeter (and Foremost is well-suited to fly these large MALEs).

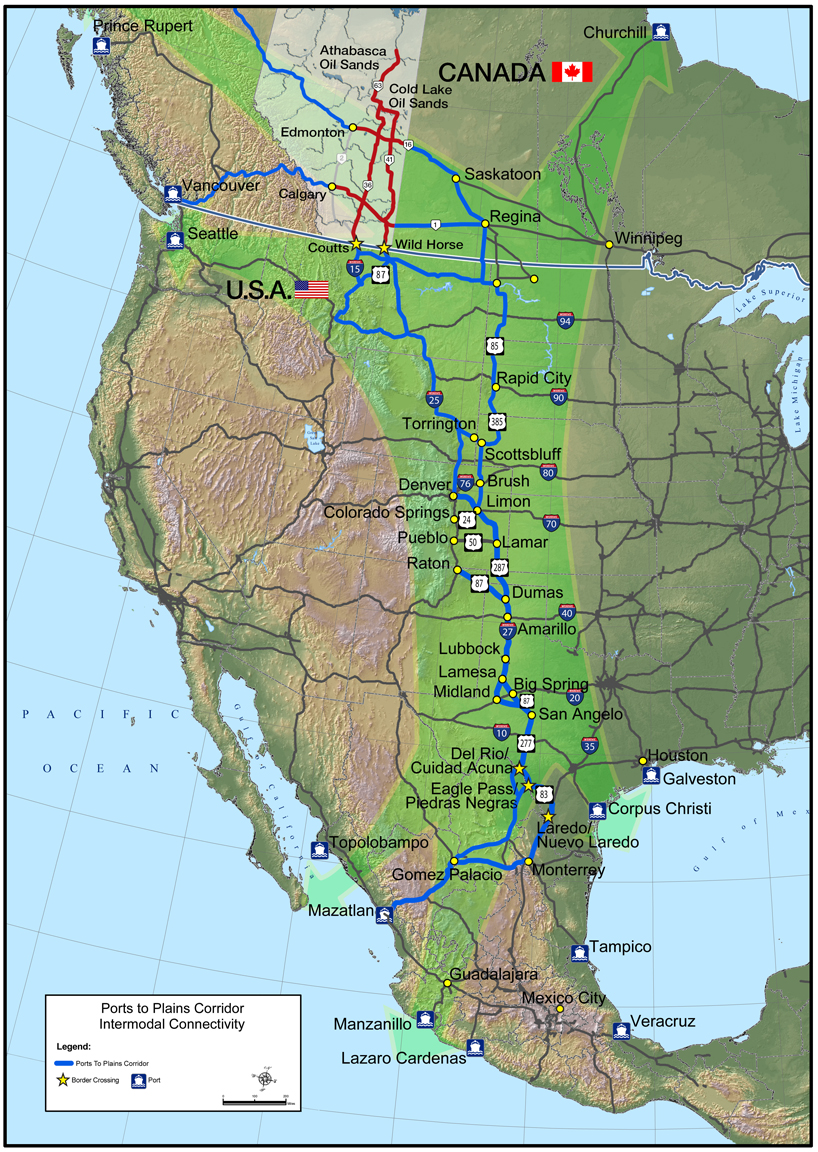

Moreover, when it comes to Canada’s nascent drone industry, borders are doubly beneficial. While the surveillance industry provides one market for drones flown above Canadian soil, another has been created through difference across the border. The United States has yet to allow the flight of personal or commercial unmanned aircraft above 400 feet or beyond the line of sight, making the use and testing of commercial drones in US airspace impossible. Canada, however, simply requires drone operators to apply for a certificate for the use of drones over 35 kilograms (approximately 78 pounds) and those used for work or research purposes.10 Such loose regulation is elemental to the Foremost plan and its stated urgency. In the plan’s own words, “The UAS industry is evolving quickly, so Foremost has a short window of opportunity.”11 In addition, CCUVS is also relying on more liberalized cross-border policies set up by the North American Free Trade Agreement to court US companies. These include provisions allowing business persons in certain industries from any of the agreement’s participant countries (the United States, Mexico, and Canada) to conduct business in the other nations without a special permit or visa, as well as measures creating uniform licensing and certification processes among the three nations.12 Intended to create conditions amenable to industry growth or free trade without containing, defining, or delimiting it, these policy frameworks have produced the certain kind of infrastructure embodied by Foremost: open-ended, noncommittal, marginally material.

Such infrastructure is perhaps most clearly manifest in the East Alberta Trade Corridor, a half-road system, half-business initiative into which the Foremost Aerodrome is supposed to plug. The corridor comprises a network of existing highways, proposed high-volume highways, and Major Capital Projects that will together link oilfields in the north of the province to the cities of Edmonton and Alberta, and to ports of entry along the Canada–US border. It’s a constellation of existing material conditions, reformulated opportunities, and industry boosterism that leverages government funds to solicit private investment in development that speeds the flow of Canadian oil to US and Mexican ports. Oil interests account for much of CCUVS’s perceived customer base; its proximity to the “corridor” is touted throughout the plan as well as on the CCUVS website. But beyond simply being discussed as a convenient adjacency, the “corridor” serves as a spatial allegory though which to understand Foremost as a system. The plan aligns scattered interests into one sleeve of space and attempts to linearly connect a complex network of conditions toward one tangible end: defining a new market.

Much like the American automobile industry relied on highways as a means to promote cars—which is to say using an infrastructure to promote the object that it's intended for—the CCUVS is using an airstrip to promote drones. Positioned and represented through the plan and other media, the little strip at Foremost becomes a site to demonstrate conditions spanning a range of scales and materiality, such as weather, geography, resources, and legal regulation, and how they can best be instrumentalized. Because more than drones themselves, what the business plan is promoting is a form of air rights—the key move in the CCUVS’s attempt to harness this previously unused natural resource, a certain portion of the southern Alberta skies.

Air rights first arose with the advent of commercial aviation. In 1926, the US government’s creation of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) turned the air above 500 feet into public domain, while the airspace below was deemed private property held by its terrestrial landowner. Railroads were the first infrastructural industry to seize the potential of such ownership, with one famous example being the New York Central Railways and the New Haven Railways’ 1958 decision to develop the Pan Am tower above Grand Central Terminal.13 Similarly, the City of Boston sold its air rights above the portion of the Massachusetts Turnpike that cuts through downtown (known as the Big Dig) to the mall mogul Adam Weiner in 2013.

But at Foremost, above one of the more modest swaths of pavement in southern Canada, it’s the ability to use the air that is being sold. This may explain why the Aerodrome itself is still a shoddily paved, weed-ridden affair, littered with shotgun shells, serviced by a shack-like structure, and protected by a “No Trespassing” sign. With so much focus turned to the atmospheric space above it, and to the alliances that will make the “unmanned systems sector” flourish, little attention seems to have been put into its solid, earth-bound component, or to the town of Foremost that the plan is allegedly intended to benefit—for though the CCUVS has received grants from the Albertan government for rural economic development, such development is tough to trace. Foremost’s residents could use a bit of infrastructure, like paved roads, or reception towers for wireless communication. They could also potentially use Unmanned Aircraft Vehicles, which could conceivably be handy for farming. But the plan makes no mention of the community that originally created, and still uses, the Aerodrome; there are no promises to do anything in Foremost but lay the groundwork for an industry that might instigate something resembling job creation or bring more money to the town’s barely existing hospitality trade. This isn’t to say that public benefits are entirely inconceivable in the future. The plan’s business model section does discuss potential revenue-generating related industries, such as “product development and commercialization advisory services,” and “intellectual property assistance.” But as of yet, what CCUVS is promoting is an airstrip for occasional crop duster use, which lacks the requisite power or water access for any sort of future facility that could be built alongside it, or a paved road to get there—the foremost investments that a town like Foremost needs.

Indeed, the sort of trickle-down economic development articulated by the plan makes no allowance for these sorts of on-the-ground investments and allocates no responsibility for making them happen. Growing Alberta’s aerospace ecosystem apparently makes no provision for the structures and people on which such an ecosystem may rely. Canada’s unmanned systems sector will likely grow, but if hinged in this way—on a nebulous constellation of legal allowances, border conditions, and regional business interests, guised in a rhetoric of rural development—could the lesson at Foremost be, if you don’t build it, they might not come? What the CCUVS offers is an unmanned urbanism, its sense of a publicness as vacant as it understands the village of Foremost itself to be. During the summer months CCUVS ceases operation “to avoid disruptions to the local agricultural community.”14 This is the time when the Aerodrome is used. Little biplanes taxi off from it, trailing mists of fertilizer and pesticides; hovering low in uncontrolled airspace, for them the CCUVS is immaterial.

-

This is the Red Coat Trail, a historic stretch of highway tracing the route taken by the North-West Mounted Police on their in their 1874 march “to bring law and order to the Canadian West.” See The Red Coat Trail website, link. ↩

-

Indeed, upon crossing the border into Coutts, Canada, the Canadian Border Services agent whom the author asked for directions suggested she simply go somewhere else. ↩

-

On Visual Flight Rules see: “Take Five: VFR Weather Minima,” Transport Canada website, May 20, 2010, link. On the sunny Albertan prairie, see “Sunniest Cities in Canada: The Cities with the Most Sunshine in the Country,” the Huffington Post, October 26, 2013, link. ↩

-

As the Foremost UAS Range Business Plan states, “It is important that this initiative [the creation of the Foremost Centre for Unmanned Systems] is seen as the ‘Foremost’ destination for UAS training and development.” Foremost UAS Range Business Plan: Growing Alberta’s Aerospace Ecosystem, 17, link. ↩

-

“The Foremost UAS Range has many of the necessary requirements to be a unique facility for UAS companies to train and develop this technology. With a relatively small investment in facilities and ramp-up costs, Foremost would leapfrog ahead of other available training options to become a world-class facility with an unmatched combination of location, geography, topography, weather, size, facilities, and restricted airspace for BVLOS flight.” Foremost UAS Range Business Plan, 2. ↩

-

For more information on the BVLOS-permitted parties in the United States, see “The Drone Exemptions Database,” Center for the Study of the Drone website, link. ↩

-

Foremost UAS Range Business Plan, 17. ↩

-

“Numerous large OEM aerospace companies have indicated an interest in flying at the Foremost UAS Range including Lockheed Martin Canada, General Atomics, and Selex-Galileo, among others. These larger companies are interested in flying at Foremost, in part, because of its proximity to them in western North America. They deem the size of the airspace sufficient for test and training flights even for UAS as large as the General Atomics Predator (i.e., figure 8 laps within the Foremost restricted airspace at Predator cruising speed will be approximately one hour in duration).” Foremost UAS Range Business Plan, 13. ↩

-

Foremost UAS Range Business Plan, 3. ↩

-

“Flying a Drone or an Unmanned Air Vehicle (UAV) for Work or Research,” Transport Canada website, December 23, 2015, link. ↩

-

Foremost UAS Range Business Plan, 2. ↩

-

See, North American Free Trade Agreement, Chapter Sixteen, Section Five, Annex 1,603, link; and North American Free Trade Agreement, Chapter Twelve, Section Five, Article 1,210, link. ↩

-

It’s a strategy also famously deployed by presidential candidate Donald Trump, whose Trump World Tower amassed the air rights of seven adjacent buildings to become what was, when it was built in 2001, the world’s tallest residential tower. ↩

Caitlin Blanchfield is Managing Editor in the Office of Publications at Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and an editor of the Avery Review.